Just a few days ago, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights summarised the state of world affairs as follows: Oppression is fashionable again; the security state is back, and fundamental freedoms are in retreat in every region of the world. Shame is also in retreat…And we have all seen it.

The rise of xenophobia, nationalism, racism, populism and the strongman leader. More and more are sensing the greater space that now exists to advance political ambition by blaming minorities and other vulnerable groups for real or perceived economic and social challenges.

Advertisement

Those seeking asylum from conflicts around the world are being framed as posing an existential threat to the identity and values of the countries they are seeking refuge in. The international human rights framework is being held out as not fit for purpose to meet the challenges of globalisation, climate change, conflict, and terrorism… The idea that what we need instead – stronger borders, higher walls and more invasive legislation that prioritises Law and Order over the Rule of Law – is gaining ground.

Advertisement

Judges are being portrayed as elitist and enemies of the people, threatening the separation of powers and judicial independence. Civil society is being painted as a threatening, destabilising force that needs to be monitored, regulated and suppressed.

Not long ago, most people seemed to agree that respect for human rights, the rule of law and democracy are the inevitable, global, aspirations of all societies – but not anymore. Sadly, much of this is also playing out here in Asia.

The possibility of ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity and genocide in Myanmar and the massive human rights and humanitarian crisis across the border in Bangladesh. Increasing moves to repress dissent and close political and civil society space in Cambodia – not to mention the all-out assault on democracy and the rule of law.

The deepening repression in the Philippines framed by Duterte’s offensive rhetoric – which some might say embodies the very idea of the shamelessness that the High Commissioner was referring to.

Repression in China; Thailand’s ongoing efforts to restrict fundamental freedoms under military rule and delay democratic elections; Continuing reports of violence against journalists and other independent voices in Pakistan; The fact that in India, criticism of government policies is frequently met by claims that they constitute sedition or a threat to national security. And so on.

There are many other examples around the region. In ASEAN, only two states have ratified the Rome Statute – Cambodia and the Philippines – and complaints about both their heads of state have been made to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The ICC’s announcement that it had opened a preliminary investigation into the Philippines prompted Duterte to announce that he is pulling the Philippines out of the Rome Statute. But challenges of accountability for gross human rights violations can be found all over Asia. And all the while, for a multitude of reasons, the influence of the US and Europe is on the decline here – while at the same time we are seeing a more assertive China seizing the opportunity and offering its political and economic support.

By way of just one example, China’s official response to the dismantling of democracy and the human rights and rule of law crisis in Cambodia was recently: “China supports Cambodia’s efforts to protect political stability and achieve economic development – and believes the Cambodian government can lead the people to deal with domestic and foreign challenges and will smoothly hold elections next year.”

“China is a good friend to have right now”, a state with a questionable human rights record in the region might say. When I asked some Western diplomats why they were increasingly pursuing a policy of “quiet diplomacy” and not coming out with an assertive, persistent, unified voice on many of the urgent human rights issues in the region, they explained they had assessed “quiet diplomacy” to be a more effective strategy.

“Loud diplomacy” simply doesn’t work in Asia they told me. And they need regional allies in the face of the challenges of North Korea, the South China Sea and what’s happening in Myanmar. Sadly, now is a great time to be a leader with authoritarian ambitions in Asia. And all these countries are watching each other – and learning. And they are watching the response of the international community to see how far they will be allowed to go.

Elections

And so, against all of this, elections are on the horizon in Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia and elsewhere.

Dominant themes

To further set the scene for this event, I would like to go a little deeper and touch upon three inter-related themes we are seeing in Asia:

- The assault on the very idea of human rights and the rule of law;

- Attacks on fundamental freedoms and civic space; and

- The misuse of the law.

Another could be the incredible economic growth we are witnessing all over the region – often unregulated and at a heavy cost to human rights.

But I will leave that to others to discuss in detail.

Assault on the idea of human rights and the rule of law

There were huge advancements in establishing an international human rights and rule of law legal framework after the Second World War – an incredible achievement, which we now take for granted.

One was the introduction of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – which is celebrating its 70th anniversary this year – which begins: The recognition and realisation of universal human rights is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world – and is the highest aspiration of the common people.

Nine key human rights treaties creating binding international legal obligations followed. A permanent international criminal court was born to fight impunity and provide redress and accountability for international crimes… an astonishing development. Regional human rights mechanisms such as the European Court of Human Rights, which has the power to issue decisions binding on member states, were created.

The Human Rights Council was established – an inter-governmental body within the United Nations system responsible for strengthening the promotion and protection of human rights around the globe. I have been fortunate to serve at two international criminal tribunals and can attest to the solemn values they stand for and the commitment of those who work within them.

While they are all imperfect, that they exist at all is a monumental achievement. Likewise, with the Human Rights Council in Geneva, where I have also had the honor of speaking.

It is quite a sight to see the countries of the world come together with the aim of strengthening the promotion and protection of human rights everywhere. But the existence of these rights – and the institutions created to promote and protect them – are under threat globally. And Asia is one of the frontlines.

Living and working in Asia these past ten years, I often hear the idea that human rights are a Western concept that is being imposed on Asia. That in Asia, ‘Asian values’ work better – and ideas such as democracy should have a local flavor, such as “Thai-style democracy.”

But a rudimentary study of the origin of the human rights legal framework set up after WWII debunks this. Examples of the promotion of freedom and tolerance have existed in Asia for centuries. And it was a group of countries from the Global South, including Jamaica, Ghana, the Philippines, Liberia, Costa Rica and Senegal, which pushed the human rights agenda after WWII.

They were the ones who fought for a stronger human rights system with legally binding components. It was not until the 1970s that Western countries started to pick up their own momentum. The fact that the Philippines is currently in a protracted war of words with several different international human rights mechanisms is therefore all the more disappointing.

Attacks on fundamental freedoms

There are examples all over the region of the repression of fundamental freedoms. Right here in Thailand, it is currently unlawful to hold a political gathering of five or more people. This year alone, and we are only in March, Thailand has charged more than 70 persons with violating the ban for merely peacefully protesting.

Lao PDR has just introduced legislation closely regulating civil society – similar to laws recently passed in Cambodia. And of course, China has its own Foreign NGO law.

Last year Cambodia shut down one of the main English language newspapers, several radio stations, and detained two Radio Free Asia journalists.

Myanmar recently detained two Reuters journalists for allegedly violating the Official Secrets Act. Sedition has also been threatened – or invoked – against journalists in other countries such as Thailand, India, and Malaysia.

Reporters without Borders, which compiles an annual press freedom, said of 2017: “The 2017 World Press Freedom Index reflects a world in which attacks on the media have become commonplace and strongmen are on the rise. We have reached the age of post-truth, propaganda, and suppression of freedoms – especially in democracies.”

Speaking of which, we are only beginning to understand the role of social media in the so- called “post-truth” world in Asia. This year, in Indonesia, the police reportedly announced that they had uncovered a clandestine fake news operation on Facebook designed to corrupt the political process and destabilize the government.

A couple of weeks ago, legal proceedings were filed in the USA seeking information from Facebook “regarding Hun Sen’s misuse of social media to deceive Cambodia’s electorate and to commit human rights abuses.”

In Sri Lanka Facebook is being blamed for spreading hate speech that led to the recent communal violence. Yanghee Lee, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar just a few days ago talked about the use of Facebook to incite violence and hatred against the Rohingya and other ethnic minorities, saying: “I am afraid that Facebook has now turned into a beast, and not what it originally intended.”

And if we are not careful, all of this will result in states asking for even greater powers to surveil the online world, in a manner inconsistent with the rights to privacy and free expression. And the security states that the High Commissioner referred to will continue to grow.

Misuse of the law

What many of these themes have in common is the misuse of the law. Rather than simply violating the human rights of people and seeking to hide or deny it, States are increasingly legislating to allow for it – to make violations ‘lawful’.

Take for example the military order in Thailand than bans political gatherings and allows for the detention of persons in military bases for up to seven days without charge. The power to issue this order was given by the interim Constitution and has the status of law. Or the numerous laws criminalizing free speech – from criminal defamation to various computer related crimes that we see all over Asia.

Or the recent proposed amendments to the Cambodian Constitution that impose a duty on all Cambodian citizens to: Primarily uphold the national interest and not conduct any activities which either directly or indirectly affect the interests of the Kingdom of Cambodia Without any definition of what any of this means and or what actions might put someone in legal jeopardy.And then all of this is justified on the basis of “the Rule of Law” – explicitly. They actually say it.

Cambodia, which is one of the leading examples of this tactic, last month even had the shamelessness to put out a White Paper entitled “Strengthening the Rule of Law and Liberal Democratic Process”.

When diplomats approach these states to enquire why laws inconsistent with human rights are being passed and used to violate human rights, the government can then claim that no one is above the law – and that they are merely implementing the Rule of Law. Of course, this is not what the Rule of Law means.

The ICJ has been working on defining the Rule of Law and making the link between it and the protection of human rights since the early 1950s – one such ICJ Congress was even held here in Bangkok in 1965.

What I have been describing, the “weaponisation” of the law – is precisely the opposite of the Rule of Law, the three pillars of which are equality, accountability and predictability. It does not just mean passing laws and holding people to them – but rather passing and implementing laws in a way that complies with international human rights law. The relationship – and interdependency – of democracy, human rights and the rule of law was recognized at the highest levels of the UN in 2012 with the adoption of a resolution at the Human Rights Council:

“Democracy includes respect for all human rights and fundamental freedoms…as well as respect for the Rule of Law.”

So what can be done?

This is the question I am looking forward to hearing answered today. But I will begin with some of my ideas. We need to recognize and fight back against these trends – as journalists, lawyers, politicians, and as people who simply wish to see justice, peace and sustainable development in the world.

And we need to do it today. We need to take responsibility. One of the things the past four years have shown us is how quickly the landscape of the world can change. We must remain vigilant.

When the kinds of trends and violations I have been describing come thick and fast it is easy to see them as overwhelming – and it becomes tempting to submit to them as being “just the way Asia is now”.

That the ‘experiment with western democracy and western human rights is over, and the region can return to its Asian Values.’ Lawyers must continue to play their important role in launching strategic litigation cases challenging the kinds of laws I have been describing and seeking access to justice for victims of violations. Judges must continue to place checks and balances on the legislative and executive branches of government.

Those of us in the business of human rights and the rule of law need to become better communicators and find new audiences and champions, including amongst the business community.

Countries should prioritize discussing human rights in their bilateral and multilateral engagements.

Journalists must continue to highlight abuses without fear or favour. The UN must keep “human rights upfront” not just in words but actions. There has to be more regional leadership, including by countries with strong rule of law in the region, such as New Zealand and Australia.

The ASEAN principle of non-interference needs to be dropped in favour of real talk on human rights and the rule of law. Civil society must be boosted and protected.

And as governments become more sophisticated in misusing the law and defending their actions based on “the Rule of Law” – we too must become more sophisticated if we ever hope to keep up with the pace of change.

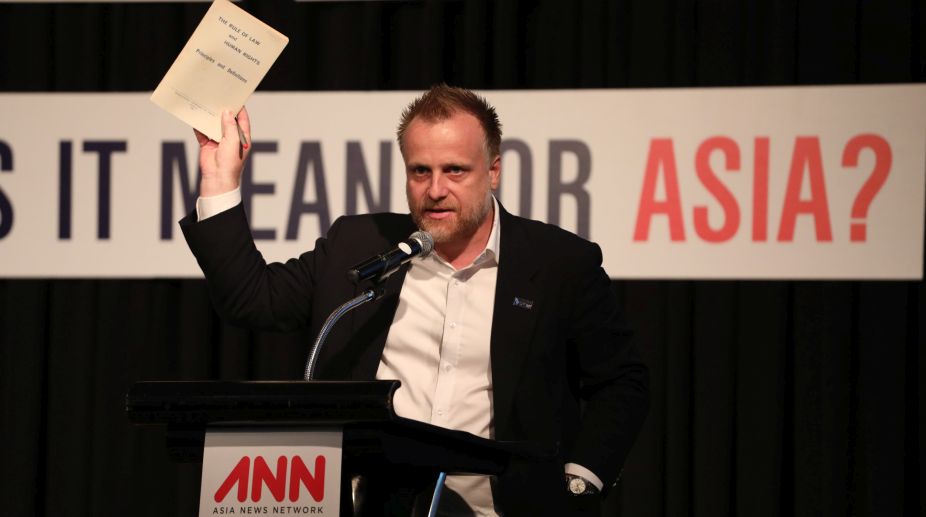

(This is an edited version of a speech by Kingsley Abbott, Senior International Legal Adviser of the International Commission of Jurists at an Asia News Network symposium “Election 2018/9: What does it mean for Asia?” The event took place on Mar 16 in Bangkok. ANN is an alliance of 24 leading media in 20 Asian countries.)

Advertisement