Iran’s choices

The tragic death of President Ebrahim Raisi in a helicopter crash has thrust Iran into a period of intense political upheaval and uncertainty.

It signaled the protege of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, the judiciary chief Ebrahim Raisi had won a vote he dominated after the disqualification of his strongest competition.

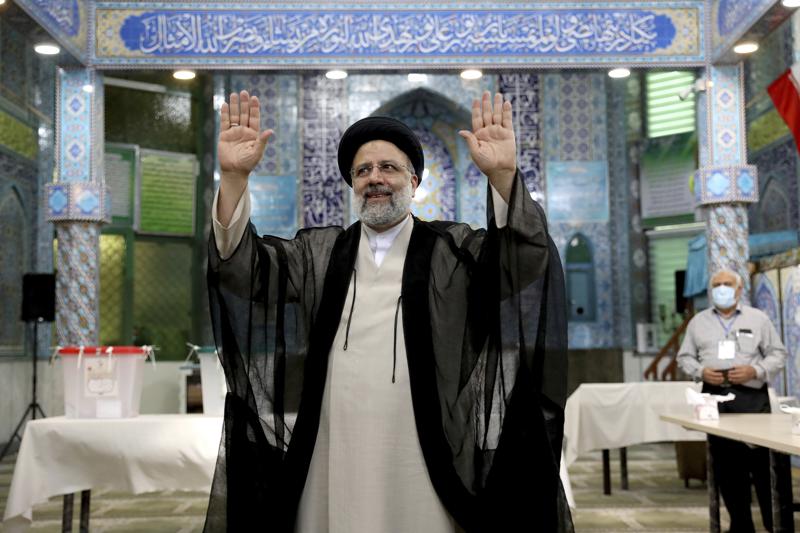

Ebrahim Raisi, a candidate in Iran's presidential elections waves to the media after casting his vote at a polling station in Tehran, Iran Friday, June 18, 2021

The sole moderate in Iran’s presidential election conceded his loss early Saturday to the country’s hard-line judiciary chief. It signaled the protege of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei had won a vote he dominated after the disqualification of his strongest competition.

Both moderate and former Central Bank chief Abdolnasser Hemmati and former Revolutionary Guard commander Mohsen Rezaei offered their congratulations to Ebrahim Raisi. Counting, however, continued from Friday’s vote and authorities had yet to offer any official results.

Advertisement

Opinion polling by state-linked organizations, along with analysts, indicated that Raisi — who is under U.S. sanctions for his role in mass executions — was the front-runner in a field of only four candidates. That led to widespread apathy among eligible voters in the Islamic Republic, which long has held up turnout as a sign of support for the theocracy since its 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Advertisement

The quick concessions, while not unusual in Iran’s previous elections, signaled what semiofficial news agencies inside Iran had been hinting at for hours: That the carefully controlled vote had been a blowout win for Raisi amid calls by some for a boycott.

Hemmati offered his congratulations on Instagram to Raisi early Saturday.

“I hope your administration provides causes for pride for the Islamic Republic of Iran, improves the economy and life with comfort and welfare for the great nation of Iran,” he wrote.

On Twitter, Rezaei praised Khamenei and the Iranian people for taking part in the vote.

“God willing, the decisive election of my esteemed brother, Ayatollah Dr. Seyyed Ebrahim Raisi, promises the establishment of a strong and popular government to solve the country’s problems,” Rezaei wrote.

As night fell Friday, turnout appeared far lower than in Iran’s last presidential election in 2017.

The balloting came to a close at 2.a.m. Saturday, after the government extended voting to accommodate what it called “crowding” at several polling places nationwide. Paper ballots, stuffed into large plastic boxes, were to be counted by hand through the night, and authorities said they expected to have initial results and turnout figures Saturday morning at the earliest.

“My vote will not change anything in this election, the number of people who are voting for Raisi is huge and Hemmati does not have the necessary skills for this,” said Hediyeh, a 25-year-old woman who gave only her first name while hurrying to a taxi in Haft-e Tir Square after avoiding the polls. “I have no candidate here.”

Iranian state television sought to downplay the turnout, pointing to the Gulf Arab sheikhdoms surrounding it ruled by hereditary leaders and the lower participation in Western democracies. But since the 1979 revolution overthrew the shah, Iran’s theocracy has cited voter turnout as a sign of its legitimacy, beginning with its first referendum that won 98.2% support that simply asked whether or not people wanted the Islamic Republic.

The disqualifications affected reformists and those backing Rouhani, whose administration both reached the 2015 nuclear deal with world powers and saw it disintegrate three years later with then-President Donald Trump’s unilateral withdrawal of America from the accord. Former hard-line President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, also blocked from running, said on social media he’d boycott the vote.

If elected, Raisi would be the first serving Iranian president sanctioned by the US government even before entering office over his involvement in the mass execution of political prisoners in 1988, as well as his time as the head of Iran’s internationally criticized judiciary — one of the world’s top executioners.

Advertisement