Using a ground-based telescope, astronomers have detected large quantities of methanol around Saturn moon Enceladus – a finding that may have implications in the search for alien life.

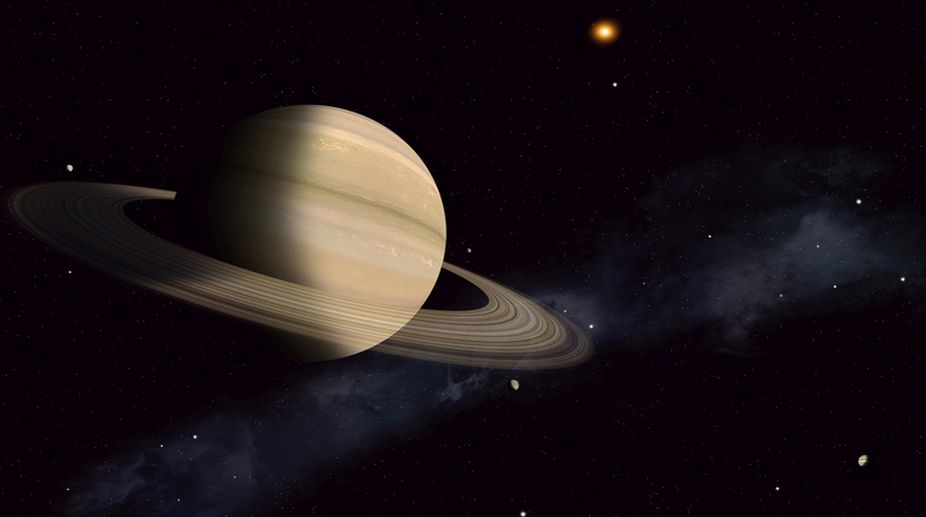

Enceladus's plumes are thought to originate in water escaping from a subsurface ocean through cracks in the moon's icy surface. Eventually these plumes feed into Saturn's second-outermost ring, the E-ring.

Advertisement

"Recent discoveries that icy moons in our outer Solar System could host oceans of liquid water and ingredients for life have sparked exciting possibilities for their habitability," said Emily Drabek-Maunder of Cardiff University in Britain.

"But in this case, our findings suggest that methanol is being created by further chemical reactions once the plume is ejected into space, making it unlikely it is an indication for life on Enceladus," Drabek-Maunder said.

The findings, presented at the National Astronomy meeting at the University of Hull in Britain, suggest that material spewed from Enceladus undertakes a complex chemical journey once vented into space.

Past studies of Enceladus have involved the NASA/ESA Cassini spacecraft, which has detected molecules like methanol by directly flying into the plumes.

Recent work has found similar amounts of methanol in the Earth's oceans and Enceladus's plumes.

In this study, the researchers detected the bright methanol signature using the IRAM 30-metre radio telescope in the Spanish Sierra Nevada.

"This observation was very surprising since it was not the main molecule we were originally looking for in Enceladus's plumes," Jane Greaves of Cardiff University said.

The team suggests the unexpectedly large quantity of methanol may have two possible origins: either a cloud of gas expelled from Enceladus has been trapped by Saturn's magnetic field, or gas has spread further out into Saturn's E-ring.

In either case, the methanol has been greatly enhanced compared with detections in the plumes.

"To interpret our results, we needed the wealth of information Cassini gave us about Enceladus's environment. This study suggests a degree of caution needs to be taken when reporting on the presence of molecules that could be interpreted as evidence for life," team member Dave Clements of Imperial College, pointed out.

Cassini will end its journey later this year, leaving remote observations through ground and space-based telescopes as the only possibility for exploring Saturn and its moons – at least for now.

"This finding shows that detections of molecules at Enceladus are possible using ground-based facilities. However, to understand the complex chemistry in these subsurface oceans, we will need further direct observations by future spacecraft flying through Enceladus's plumes," Drabek-Maunder said.