The Sawan-Badhon pavilion of the Red Fort is now bereft of swings, from which Mughal princesses used to swing their romantic urges away

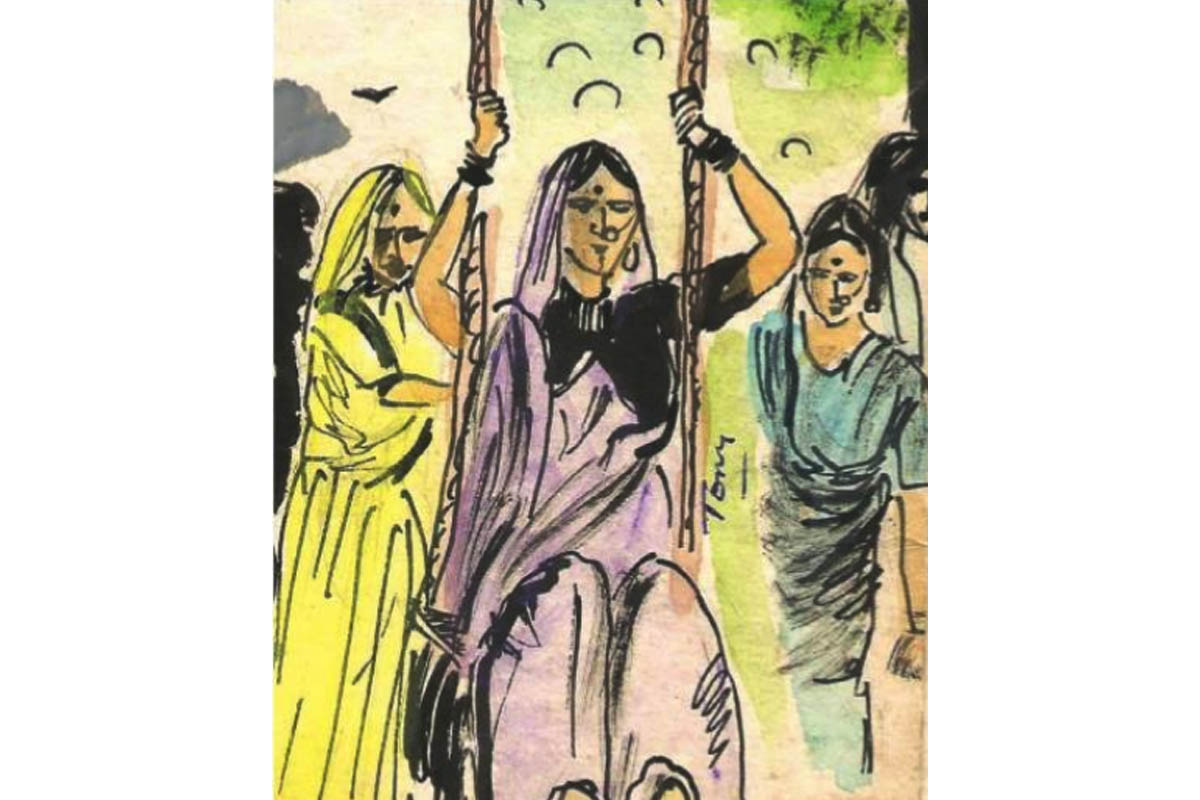

The rainy months are said to be intoxicated with love, especially Sawan, which has been compared to a mast (passion crazed) elephant. Kalidas’s Meghdootwould have us believe that lovers sperated by long distances send their messages through the rain clouds. Some women longing for their absent sweethearts swing away their blues. Hence the popularity of swinging fairs which, alas, are now more or less a thing of the past, except in the rural areas and some semi-urban pockets. The swings of Teej that come up in Delhi are just a token reminder of the olden days, when rope jhoolaswere put up in courtyards and on trees so that women and girls could swing away the masti induced by Sawan-Bhadon. Of course, not all of them were mast ~ some just did it for instant thrills on a dull afternoon after they were through with household chores.

Advertisement

One remembers the big jhoolas that used to be hung from the tallest trees in the compound of a Nawab Sahib. The Negroid family descended from Almas, who had been bought by the Nawab’sfather at a slave market in Mecca during the last decades of the 19th century, was in charge of the swings. There were three sisters among them ~ Mubarak, Hasina and Amina ~ who, along with their mother, Mahruka, and the cook Chhoti, sang ditties of “Balma” (beloved) and pushed the swings with great gusto for the purdanladies. Enjoying themselves with the “Jhonkas” were the three Bubusof the Kothiall daughters of the Nawab Sahib ~ their mother, Dulhan Sahib, the residents of nearby Rashid Manzil ~ Dulhan Chachi, Bibbi Behn, Rehmat Bua, Khaleda, Zahida and Tahira, and two Christian ladies, Ruby and Natalia. What fun they had with plenty of sherbet and sweets in the pre-Partition days!

In the Mardana, or men’s quarters, Almas, his sons, Yakub, Salim and Naeem, along with a comical character called “Murgha Katgo”, pushed the swings for the Nawab’s sons, Bade Mian, Manjhle Mian, Chote Mian, and their friends. All that is a distant memory now. In Delhi, the Sawan-Badhonpavilion of the Red Fort is bereft of swings, from which Mughal princesses used to swing their romantic urges away. But Sawan and Bhadon still cast their spell, not only over the fort but elsewhere too. And when they come can the rain bird lapwing (tateeri) be far behind?

Misnamed the brainfever bird because of its shrill cry, it has been the subject of much comment down the centuries. Why should this rainbird, which is said to have a hole in its throat, live on a terrace overgrown with monsoon grass that has a tendency to cling to houses like an unwanted guests? People sleeping under swirling fans and sweating it out on a hot oppressive night (without the benefit of desert coolers and AC’s) wake up with a start on hearing its cry and murmur, “Rain, rain”. The belief is that the bird can only slake its parched throat with raindrops, so whenever its needs a drink of water it calls out to the skies and the clouds of Sawan oblige. Of course, an ornithologist would have a different story to tell, but to keep up pretences one would like to think the rain bird really has fever on its brain and needs the previous droops from heaven to calm it down. Probably summer pools can hardly cool the fever on its brow.

One result of pollution and the scanty water in the Yamuna is the virtual end of the annual swimming fairs. The Delhi Gazatteerof 1883-84 recorded the number of fairs in Delhi at 33, though originally there were 104, which included (besides the bathing ones) mostly those in honour of local deities, the pankhamelas, the Moharrum processions and the Urs at various shrines. Among the fairs that attracted both Muslims and Hindus were the Tairaqi Melas, first started by the Mughals during the rainy months, when the river was full and flowed right under the walls of the Red Fort. Nets had to be thrown in it to catch crocodiles that were swept thither by the flood. There may be some exaggeration in such accounts, though it is a fact that occasionally ensnared crocs found their way to Macchliwalan, the fish market near the Jama Masjid, where oil was extracted from their carcasses and, like their skin and teeth, fetched a high price, along with the snout that was mounted by taxidermists for the drawing rooms of the nawabs and nawabzadas. Until the late 19th century crocodiles were found basking near the Purana Qila in winter and shot by British sentries, according to the Gazetteer.

Here is an account written in the mid-20 th century: “For most Delhi wallahs the swimming season begins with the onset of the monsoon and not at modern swimming pools. There was a time when swimmers floated on their backs with iron spits on their chests on which kababs, paranthas and jalebis were fried. In Mughal days the art of swimming reached its zenith with Tairaqs from Turkey, Iran, Armenia, Central Asia and Afganistan coming to complete here. A noted swimmer from Agra was given the title of Mir Macchli by Jahangir. It is said that when Jahangir, as Prince Salim, was initiated into the sport, tons of roses were thrown into the Yamuna, then in flood. A similar story is told about Shah Jahan, which only goes to show how popular river swimming was in those days even for princes.”

Up to the early 1940s there were four swimming fairs on the four Thursdays of Sawan. Parties of swimmers from the Walled City marched to the river to the beat of drums, headed by a flag-bearer (the Nishan Nashin), and singing the songs of “Barsat” of poet Nazir. There were separate groups of Muslim and Hindu swimmers. For the former the Ustad was the chief and for the latter the Khalifa(colloquially pronounced Khalipa). This was strange since the word Khalifa has Arabic origins and got converted into the Anglicised “Caliph”. How come then that a non-Muslim group had adopted it? One reason could be that in former times the trainers of both communities were of Turkish descent and so when “Ustad” became popular with one group, the other one decided on retaining “Khalifa”.

Parmal Khalifa was actually a fat, paunchy vegetable seller, who walked with difficulty. But when he entered the river he was grace sublime, braving the currents and leading his team into the most tricky parts of the Yamuna.

Ghafoor Ustad was a balding pigeon-fancier who used to jump from the old river Bridge into the flood water, holding the Nishanin one hand and swimming with the other ~ a tight-fitting cotton Lucknavi cap on his head. Both Muslim and Hindu groups swam across the river and when they reached the other side they offered “Chiraghi” (lamps) one on a mazarand the other under a pipal tree. The groups returned home with the drums beating again and the Nishan fluttering in the monsoon breeze to cries of “Nare Taqbi” and “Har har Mahadeva,” as per their belief. But if a group lost a swimmer (a rare occurrence) then the drums were not played and it trooped home silently. Because of this fear little girls and boys were posted on the road to bring word to the zenanawomen that all was well and that their group was returning with “deecham-deecham” (joyous drumbeats) and mad Razzakdancing in a frenzy. It was then that kheel-batasha or sweet nuktidana (boondi) were distributed to all and sundry. In the case of a mishap the group did not return without the body of the drowned member, even if it took hours to recover it from the “bhanwar” or the treacherous circular river current that was a virtual death-trap.

One remembers meeting Munne Mian, an old ustad staying in Kucha Chelan in the 1960s, who had a host of stories to relate in his spare time. Though he had stopped swimming, his son had taken over the ustadiand the turban that went with it. One story concerned Masoom, a boy of 16, who was presumed drowned in the last fair of Sawan.

The group searched for him but couldn’t find the body and wanted to return home. Munne Mian, however, was not the one to give up and eventually found the boy caught in the “bhanwar”. He carried him to the Yamuna bank, put him on his stomach and squeezed the water out of his lungs. He then massaged the body till breath returned and then the Nishanwas hoisted and the group returned triumphantly, with Masoom being carried in a sort of relay throughout. One hardly hears of such fairs now!