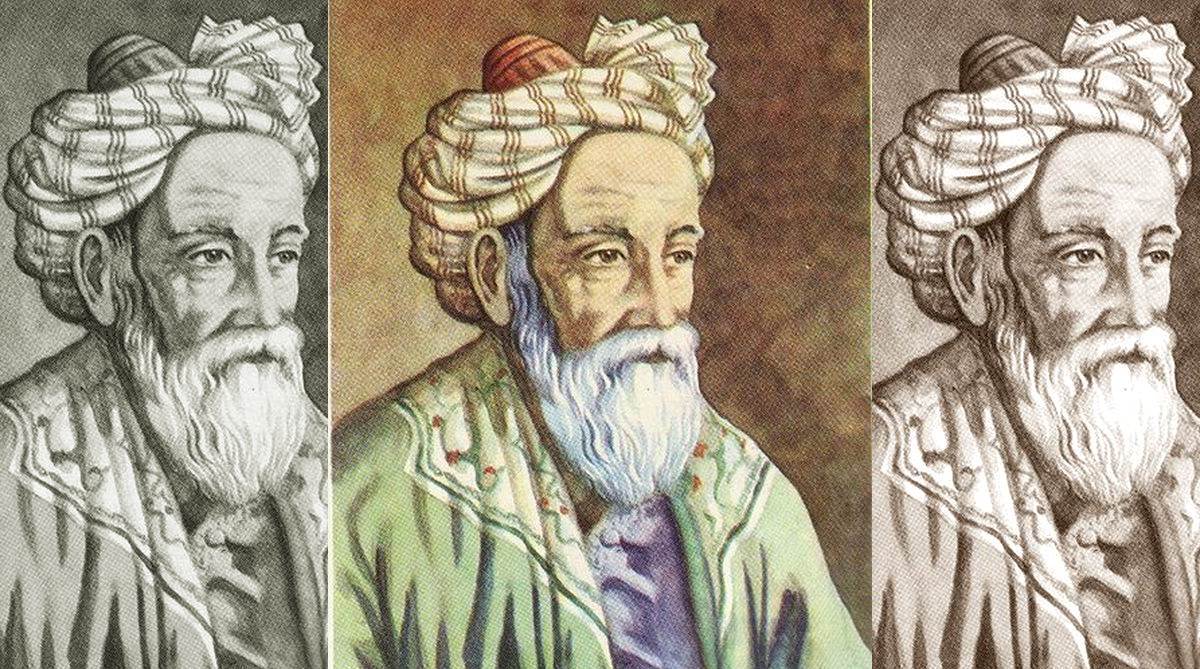

Omar Khayyam, whose Rubaiyat has charmed millions of hearts in all countries, including our own, is still not rated very highly in his native land, Iran, where the orthodox find his views incompatible with the teachings of Islam.

But people in India still fall in love with his philosophy as I did one evening and was reminded of it when author Jalil quoted from the Rubaiyat at the recent Jaipur Literary Festival. The tentmaker (for that is what Khayyam means) of Naishpur shot into frame because of the translation of his rubais by Edward Fitz Gerald (1809-1883) in Victorian England. There are five versions of the Rubaiyatby Fitz Gerald, which show that he had not actually attempted a translation but his own interpretation of the Persian quatrains. Two versions were also preserved in the Jaipur City Palace as Madho Singh II was fond of the women, wine and song that personified Omar’s poetry. Its late curator Yaduendra Sahai later saw them at the Albert Hall Museum. They belong to the time of Mirza Raja Jai Singh, who established the Oriental College of Persian and Arabic in the 17th century. The Asiatic Society, Kolkata is perhaps the greatest repository of the manuscripts of the Rubaiyat.

Advertisement

There are 550-odd pages preserved there and the credit for this should go to the East India Company, which encouraged its members to study Persian, Sanskrit and other eastern languages. It was Sir William Jones who translated the epic, Shakuntala, and made it known to the Western World. His knowledge of Sanskrit was just as good as Warren Hastings’ grasp of Persian. Hastings, indeed, could make an after-dinner speech in that language. And surely there where others just as good, or even better, than him. Sawai Jai Singh II for instance, who surprised Mohammad Shah’s court in Delhi with his knowledge of Persian as he had learnt Farai from an old Muslim courtier of his father, Ram Singh I.

READ | A comic salute to Omar Khayyam: The Rubaiyat and its parodies

While browsing through books on sale at the weekly bazaar that used to spring up on the Jaipur Agra Road outside Ghat Gate one rediscovered old Khayyam just as the new moon was peeping from behind a peepul tree and a muezzin called people to prayer at the Nawab-ka-Chauraha mosque, once also frequented by Meos of Haryana. The book mellowed the evening with the ever-green rubais amid the smell of hot jalebis being made by the light of a patromax lamp, which were munched by gypsy girls selling trinkets and iron utensils to burqa-clad women of Ghat Gate.

India knew about Khayyam long before Fitz Gerald. This fuelled interest in the poet, who was earlier acknowledged as a great hakim or scholar of astronomy. In fact, he was known as Hakim Omar Khayyam even in his lifetime. This was affirmed by the poet Maftoon of the De Sylva family of Jaipur’s Dariba, who was also famous as a Hakim, like his brother, who wrote Shairi under the pseudonym of “Fitrat”.

After Mahmud of Ghazni had laid waste India and amassed a fortune, his successors could not hold on to the empire he had built. Persia, as Iran was then called, was conquered by Toghrul Beg, whose son was Alp Arslan and grandson, Malik Shah. It was about that time that the legendary Imam Mowaffak held his classes in Naishpur, where Omar was born and saw pedigree horses from Rajputana being sold in the market. The three selected students of the Imam had promised each other that whoever became rich and powerful would share his wellbeing with the other two. It is surmised that during his initiation Khayyam visited the outskirts of the Thar Desert on learning tales of the treasure guarded by Mina tribesmen, who ruled before the Kachhwa Rajputs and sometimes made secret visit to bordering Iran too.

When one of the pupils of the Imam became Vazir, the other two reminded him of the promise. Hassan joined the court but was ousted because he indulged in intrigue. Afterwards, he formed a band of assassins and came to be known as the “Old Man of the Mountains”, who gave his victims a “taste of paradise and houris” by intoxicating them with hashish, from which the word “assassin” is said to have been derived. Khayyam asked just for the Vazir’s patronage so that he could continue his study of astronomy, philosophy and mathematics and the preparation of the calendar of the Jalali era (Incidentally the calendar also guided Maharaja Jai Singh when he was building his Jantar Mantars). The Nizam-ul-Mulkgave him an annual pension and Omar was satisfied with it. Among his students was the great writer Khwaja Nizami of Smarkand. Nizam-ulMulk was unfortunately assassinated on the instructions of his former beneficiary, Hassan.

A Maharaja College student, who went for his viva voice test, was asked who was his favourite writer. His reply was “Omar Khayyam”. “What is there in him, except quatrains like, ‘A book of verse, a loaf of bread, a flask of wine and the beloved singing beside him in the wilderness’?” remarked the VC of Rajasthan University, Professor VV John. But in effect it was not so mundane, for each of the things mentioned has an allegorical meaning and the wine is the intoxication of divine love, while the beloved is the mystic experience.

This line of thought was also appreciated centuries earlier by Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti of Ajmer, whose disciples indoctrinated the Sufis of Jaipur State.

Khayyam did not write his quatrains as an outlet for sensual desires. His was the quest of the mystic, which made him wonder if there was any afterlife.

“One thing is certain and the Rest is Lines. The flower that once has blown for ever dies.” He believed more in fate or destiny than in redemption, for after the Moving Finger and written neither piety nor wit (knowledge) could help to cancel half a line. The Potter, who dabbled in human clay was there and he was the Almighty, but beyond that nothing was known, except that the Potter would go on making more images and improving the earlier ones. Evolution perhaps conceptualized by a man who lived from A.D. 1050 to 1132 and who was aware of the fact that the earth rotated on its axis and revolved around the sun (the magic lantern around which we, the human figures, revolve). Gypsies (like the late Reshma), who sing in the desert sands of Rajasthan as their caravan of camels passes by on a moonlight night, are as much aware of this as any follower of the “Weeping Philosopher”, who sat in a cave and shed tears on human bondage to the whims of fate.

Bappa Rawal, the ancestor of the Rajput clans, was among those who realized this when he reached old age and decided to discard his material assets.

All this came to mind that evening when one bought a copy of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyatdirtcheap at Ghat Gate and hurried home to read it at leisure after Jalil’s reference to it at the Literature Fest, where British author Jeffrey Archer went ga-ga over R K Narayan’s Malgudi Days the next afternoon.