INS Teg strengthens India–Seychelles Naval ties with port call, parade, and joint patrols

The visit aims to bolster maritime security cooperation and enhance bilateral defence relations between India and Seychelles.

Understanding these changes is crucial for climate mitigation and adaptation efforts, essential for safeguarding our collective future.

Statesman News Service | Kolkata | May 3, 2024 12:55 pm

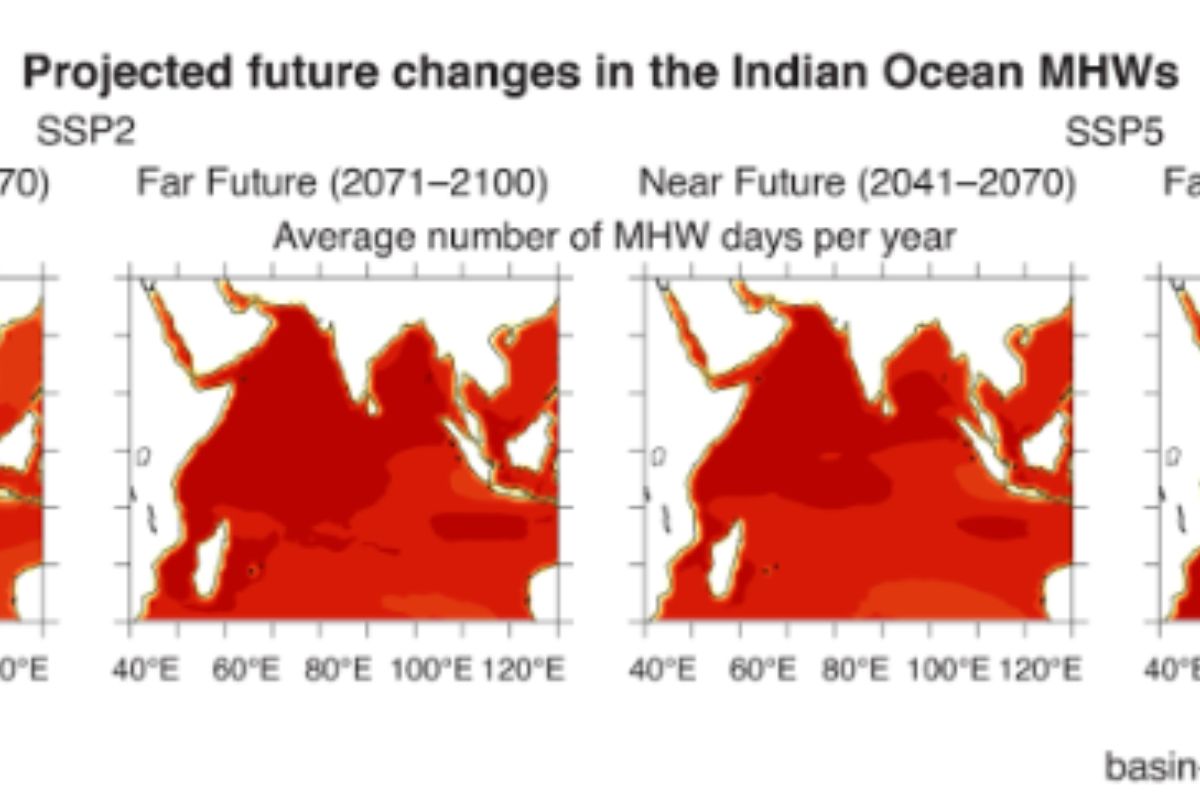

Photo: Future changes in Indian Ocean

A study led by Roxy Mathew Koll of the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune, delves into the evolving climate of the Indian Ocean and its future projections. Understanding these changes is crucial for climate mitigation and adaptation efforts, essential for safeguarding our collective future. Bordered by 40 countries, and home to a third of the global population, changes to climate in this area of the world has major societal and economic impacts. Currently, the Indian Ocean and its surrounding countries stand out globally as the region with the highest risk of natural hazards, with coastal communities vulnerable to weather and climate extremes.

Ocean is warming at a rapid pace

While the Indian Ocean warmed at a rate of 1.2°C per century during 1950–2020, climate models predict accelerated warming, at a rate of 1.7°C–3.8°C per century during 2020–2100. Though the warming is basin-wide, maximum warming is in the northwestern Indian Ocean including the Arabian Sea, and reduced warming off the Sumatra and Java coasts in the southeast Indian Ocean.

Advertisement

Seasonal cycle and weather patterns have shifted

The seasonal cycle of surface temperatures is projected to shift, which may have implications of extreme weather events over the Indo-Pacific region. While the maximum basin-average temperatures in the Indian Ocean during 1980–2020 remained below 28°C (26°C–28°C) throughout the year, the minimum temperatures by the end of the 21st century will be above 28°C (28.5°C–30.7°C) year around, under high emission scenario. Sea surface temperatures above 28°C are generally conducive for deep convection and cyclogenesis. Heavy rainfall events and extremely severe cyclones have already increased since the 1950s and are projected to increase further with increasing ocean temperatures

Advertisement

Warming is not just at the surface…

The rapid warming in the Indian Ocean is not limited to the surface. The heat content of the Indian Ocean, from surface to 2,000 metres deep, is currently increasing at the rate of 4.5 zetta-joules per decade, and is predicted to increase at a rate of 16–22 zetta-joules per decade in the future.

Roxy Mathew Koll says, “The future increase in heat content is comparable to adding the energy equivalent of one Hiroshima atomic bomb detonation every second, all day, every day, for a decade.”

…and can raise the sea level

Increase in the ocean heat content contributes to sea level rise also. Thermal expansion of water contributes to more than half of the sea level rise in the Indian Ocean, which is larger than the contribution from glacier and sea-ice melting.

Indian Ocean Dipole is getting extreme

The Indian Ocean Dipole, a phenomenon that affects the monsoon and cyclone formation, is also predicted to change. The frequency of extreme dipole events are predicted to increase by 66 per cent whereas the frequency of moderate events are to decrease by 52 per cent by the end of the 21st century.

Indian Ocean is moving to a near-permanent marine heatwave state

Marine heatwaves, periods of extremely high temperatures in the ocean, are expected to increase from 20 days per year to 220–250 days per year. This will push the tropical Indian Ocean into a near-permanent heatwave state. Marine heatwaves cause habitat destruction due to coral bleaching, seagrass destruction, and loss of kelp forests, affecting the fisheries sector adversely. They also lead to rapid intensification of cyclones, where a cyclone could intensify from a depression to a severe category in a few hours.

Ocean acidification is intensifying

Ocean acidification is predicted to intensify, with surface pH decreasing from a pH above 8.1 to below 7.7 by the end of the century.

Roxy Mathew Koll adds, “The projected changes in pH may be detrimental to the marine ecosystem since many marine organisms—particularly corals and organisms that depend on calcification to build and maintain their shells—are sensitive to the change in ocean acidity. The change may be easier to fathom when we realize that a 0.1 fall in human blood pH can result in rather profound health consequences and multiple-organ failure.”

Marine productivity is going down

The surface chlorophyll and net primary productivity is predicted to decline, with the strongest decrease of about 8–10 per cent in the western Arabian Sea.

Oxygen concentrations could also be declining

There is growing observational evidence that oxygen concentrations are declining in the tropical Indian Ocean. However, models do not agree on the future evolution of oxygen concentrations, calling for an improvement in the representation of biogeochemical processes in these models.

Act now

According to Roxy Mathew Koll, “It is crucial to recognize that the impacts of these changes are not distant concerns for our grandchildren and future generations alone. As the current generation, we are already witnessing the repercussions firsthand. Monsoon floods, droughts, cyclones, and heatwaves over both land and ocean are increasingly affecting us. These extreme weather events will amplify in intensity and frequency before we reach the twilight of our time—unless decisive action to adapt and mitigate climate change is taken now.”

Thomas Frölicher adds, “The Indian Ocean, a climate change hotspot, faces rapid and strong increases in marine heatwave frequency and intensity unless global CO2 emissions are substantially cut.”

Way forward

Addressing the impending challenges in the Indian Ocean demands a multifaceted approach. By reducing global carbon emissions and investing in resilient infrastructure, we can mitigate the impacts of climate change on coastal communities. Concurrently, conserving marine ecosystems through sustainable practices and enhancing forecasting capabilities can bolster the region’s resilience to extreme weather events. Moreover, promoting adaptive agriculture and fostering international collaboration are vital for ensuring food security and preserving biodiversity. Taking decisive action now is imperative to safeguard the Indian Ocean’s ecosystems and livelihoods for future generations.

Details of the Study

Title: Future projections for the tropical Indian Ocean.

Authors: Roxy Mathew Koll, Saranya J. S., Aditi Modi, Anusree Ashok from the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune; Wenju Cai from CSIRO, Australia; Laure Resplandy from Princeton University, USA; Jerome Vialard from Sorbonne Universités, France; and Thomas Frölicher from University of Bern, Switzerland.

Link to the study: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822698-8.00004-4

Advertisement

The visit aims to bolster maritime security cooperation and enhance bilateral defence relations between India and Seychelles.

In a unique initiative, the Indian Army on Tuesday launched ‘Chiefs’ Chintan’ — a structured two-day interaction between the Chief of the Army Staff (COAS), General Upendra Dwivedi, and former Chiefs of the Army Staff (CsOAS).

He was chairing the Global Young Scientists Conference and Annual General Meeting of the Global Young Academy at IIT Hyderabad.

Advertisement