Europe in decline?

The Nobel Prize winning Columbia University economist Edward Phelps maintains that innovation is the key to economic growth, prosperity and human happiness.

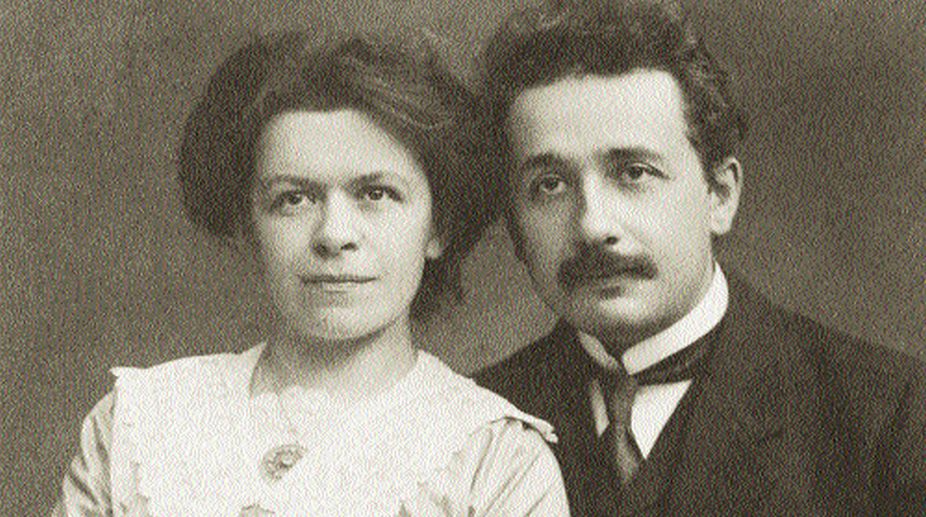

Does Albert Einstein’s first wife, Mileva Maric, deserve credit for some of his work?

The couple in 1911

For most, Albert Einstein is synonymous with genius. His face adorns classroom walls across the world and in 1999 he was announced as Time magazine’s most important person of the 20th century.

However, not many people are aware of Albert’s first wife, Mileva Maric and her participation in his scientific productivity. Maric was Albert’s wife during his most creative and formative years, yet she remained hidden in the shadows. My parents told me stories about her and I was often left dumbstruck by the thought that a Serbian woman could have actively participated in the history of modern physics.

Advertisement

Debate regarding Maric’s role in Einstein’s work has persisted for decades. One side contends that she was a collaborator and even co-authored his papers; the other says she was simply an intelligent sounding board.

Advertisement

The catalyst for this passionate debate was the release of old letters, by the family, between Albert and Mileva. These letters were later published in the books Albert Einstein/Mileva Maric: The Love Letters and The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein.

In many of the letters, Mileva can be observed sharing Albert’s scientific and mathematical enthusiasms. At certain points, she is even indicated as a collaborator. Critics argue, however, that the letters provide insubstantial evidence and that their joint work was exaggerated.

Whether Maric participated in Einstein’s theories or not, it cannot be denied that she was extraordinary for many reasons. Despite being one of the first female physicists in the world, the importance of her work has not been evaluated. Her story illuminates the plight of intellectual women during the first half of the 20th century.

Born in 1875 in Titel, Vojvodina, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and now Serbia, Maric endured a turbulent path as a girl wishing to study physics as education beyond four years of elementary school was reserved for men only. Seeing Maric’s potential, her father Milos sent her across the border to Serbia to the gymnasium in Sabac — where girls had the same educational rights as boys. Then he took a job in Zagreb (also part of Austro-Hungary) where Mileva encountered yet another hurdle.

Milos petitioned for Mileva to be accepted into the all-male Royal Classical Gymnasium. She was accepted and became one of the first women in the Austro-Hungarian Empire to sit in a high school physics lecture alongside her male peers. At the time, physics did not produce many female names.

Maric deserves recognition not only for her resistance to obstacles and bravely exploring the world of physics, but also for her pioneering role in opening the door for women after her. Eventually, she reached the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich where she was the only woman in her class.

Maric’s very presence at the university marked her as exceptional. There she met Albert Einstein, and they married in 1903.

The letters not only give us a glimpse into Mileva and Albert’s personal relationship, but also their intellectual development and shared discipline of physics. In one letter, Albert wrote to Mileva, “How happy and proud will I be when the two of us together will have brought our work on relative motion to a victorious conclusion!” In another letter he said, “I am very curious whether our conservative molecular force will hold good for gases as well.”

On many occasions, Einstein continued to write to Maric about “our new studies”, “our investigations”, “our view”, “our theory” and “our paper”. But he also heavily relied on her for emotional support. In one letter he told her: “Without you I lack self confidence, pleasure in work … without you my life is no life.”

It is claimed when addressing a group of Croatian intellectuals, Einstein said, “I need my wife as she solves all the mathematical problems for me.” It is true that Maric’s training in mathematics and physics would have allowed her to research and develop ideas with Einstein.

However, critics remain sceptical in spite of references to “our work” and “our investigation”. Some say that the use of pronouns was merely affectionate and that Maric never wrote about physics to Einstein, but rather wrote about mundane subjects.

However, later letters show Einstein did make a distinction between his individual work and what he considered a collaboration with Maric. In one he wrote, “The local Prof Weber is very nice to me and shows interest in my investigations. I gave him our paper. If only we would soon have the good fortune to continue pursuing this lovely path together.”

Clearly in this letter Einstein is talking about two different items, his own investigation and his joint collaboration with Maric. The most probable conclusion is that he was working on and referring to several ideas at once. Is it not possible that Einstein had ideas he developed with Maric and those he developed himself? Many of Maric’s letters to Einstein have been lost, the reason remaining unknown.

After Maric’s death, author Djordje Krstic recalled their son Hans Albert telling him about seeing the couple “work together in the evenings at the same table”. Despite the historical context, Maric was a physicist and her talent for the subject makes it conceivable that she and Einstein worked together.

Regarding the most controversial claim, Maric biographer Desanka Trbuhovic-Gjuric also writes about a piece that was written by the Soviet physicist Abraham Joffe. Joffe claims that he saw the original three submission papers of the 1905 theory of relativity paper and said they were signed Einstein-Marity. Marity is the Hungarian variant of Maric. However, Marity was removed from the final publication.

Both Gjuric and Joffe make a provocative claim but is it inconceivable? It is important to appreciate both the background and the context as to why Maric’s name may have been omitted from final publication.

In 20th century Europe female scientists faced many institutional obstacles and it was not uncommon for them to be excluded, despite any contribution, from scientific papers. But critics maintain that by Swiss custom the maiden name of the wife is added to the husband’s family name. Nevertheless, only Einstein’s name appeared in the scientific papers and that would continue to be the case for the rest of his work.

On 31 January 1918, Einstein wrote to Maric offering his Nobel Prize money in exchange for a divorce. However, after he had received his winnings he gave her only half. Consequently, this raised many questions. Why did Einstein use his Nobel Prize money and not regular alimony and child support? Was it half the money for half the work?

After their divorce, they maintained a steady relationship. After all, they had shared interests and two sons. Their youngest son Eduard was diagnosed with schizophrenia and Maric spent the rest of her life caring for him. She died on 4 August 1948 at the age of 72.

In the summer of 2004, Maric’s unmarked grave site had finally been identified in Northeim cemetery in Zurich under the number 9,357. I cannot help but feel that this was a poignant reflection on the life of a woman that was excluded from history.

A slim volume of letters and testimonies cannot provide answers to questions biographers and historians have been posing for decades concerning the intellectual contributions of Mileva Maric. However, their correspondence, I believe, offers a new understanding of the intellectual and emotional resources that made Albert Einstein’s path-breaking contributions possible.

Her hidden significance justifiably means her contribution to physics should be researched, investigated and evaluated. For this reason, the evidence that she collaborated, and aided Einstein’s scientific development, deserves genuine consideration.

The independent

Advertisement