Touching the Sun

The Sun, the fiery heart of our solar system, has fascinated humanity for centuries. Despite the progress of modern science, many of its secrets remain locked away, particularly the mysteries of its outer atmosphere, the corona.

“In the past, we didn’t know that stars could flare in the millimetre range, so this is the first time we have gone looking for millimetre flares,” MacGregor said.

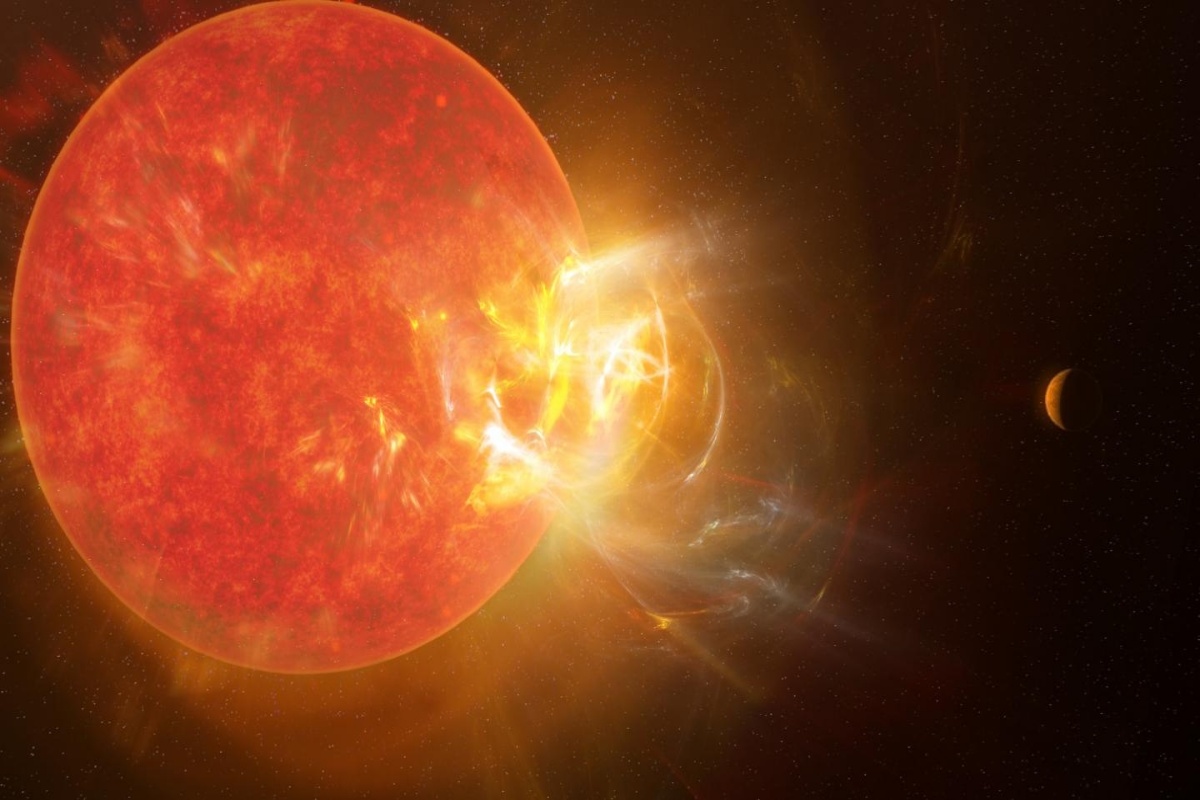

Record-breaking flare spotted on Sun's nearest neighbour.

Scientists have spotted the largest flare ever recorded from the sun’s nearest neighbour, the star Proxima Centauri.

Proxima Centauri is a small but mighty star. It sits just four light-years or more than 20 trillion miles from our own Sun and hosts at least two planets, one of which may look something like Earth.

Advertisement

It’s also a “red dwarf,” the name for a class of stars that are unusually petite and dim, explained Meredith MacGregor, astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Advertisement

For the new study, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, the team observed Proxima Centauri for 40 hours using nine telescopes on the ground and in space.

They found Proxima Centauri ejected a flare, or a burst of radiation that begins near the surface of a star, that ranks as one of the most violent seen anywhere in the galaxy. The flare was roughly 100 times more powerful than any similar flare seen from Earth’s sun. Over time, such energy can strip away a planet’s atmosphere and even expose life forms to deadly radiation.

“The star went from normal to 14,000 times brighter when seen in ultraviolet wavelengths over the span of a few seconds,” MacGregor said.

The team’s findings hint at new physics that could change the way scientists think about stellar flares. They also don’t bode well for any squishy organism brave enough to live near the volatile star.

The instruments included the Hubble Space Telescope, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. Five of them recorded the massive flare from Proxima Centauri, capturing the event as it produced a wide spectrum of radiation.

The technique delivered one of the most in-depth anatomies of a flare from any star in the galaxy. While it didn’t produce a lot of visible light, it generated a huge surge in both ultraviolet and radio, or “millimetre,” radiation.

“In the past, we didn’t know that stars could flare in the millimetre range, so this is the first time we have gone looking for millimetre flares,” MacGregor said.

Those millimetre signals, MacGregor added, could help researchers gather more information about how stars generate flares.

Advertisement