Major administrative reshuffle in Haryana

The Haryana Government has made a major administrative reshuffle and issued posting and transfer orders of 12 IAS and 67 HCS officers with immediate effect.

On the day of the incident, the closest Met stations recorded a maximum temperature of 34–38 °C, along with a relatively high humidity (45 per cent), exacerbating the impact of the heat.

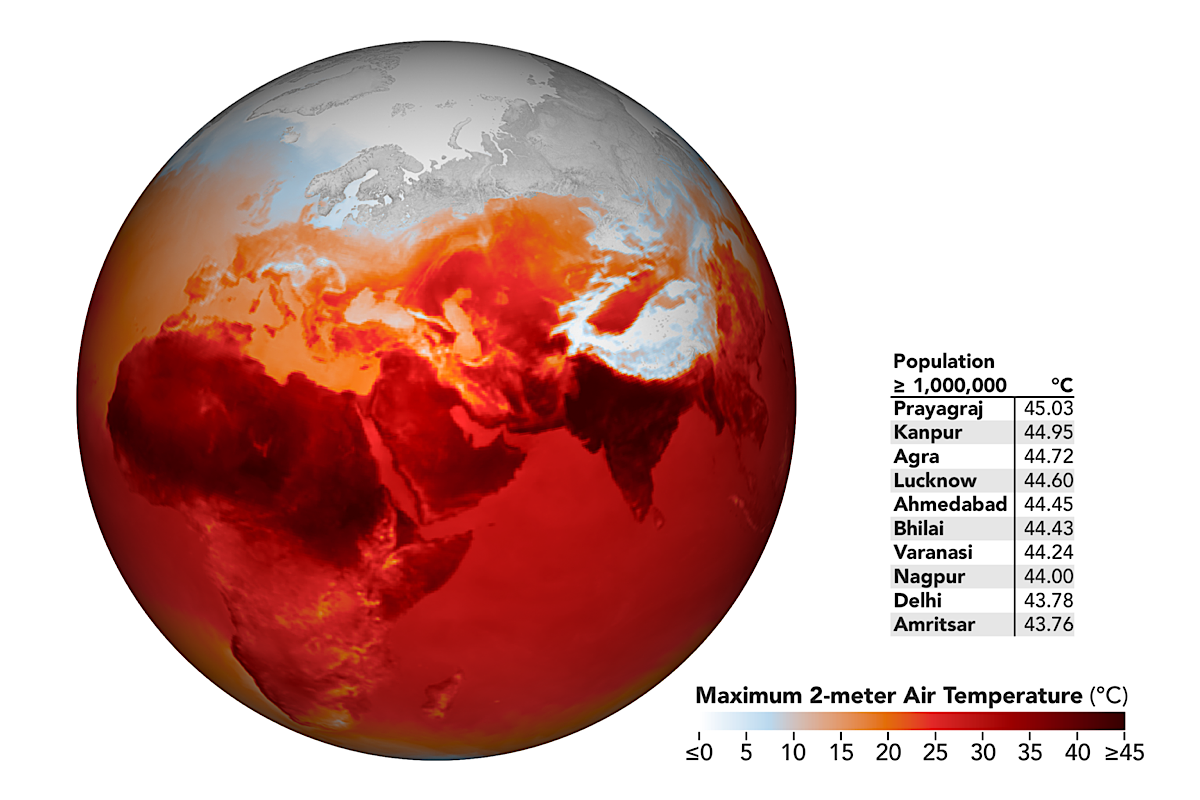

Heat wave analysis, (photo, SNS)

Fourteen people lost their lives to heatstroke on 16 April 2023, during a government ceremony held on open ground in Kharghar, Maharashtra. Ten were women—mothers—aged 34–63 years. “This was a tragedy that could have been averted with the right precautions in place.”

On the day of the incident, the closest Met stations recorded a maximum temperature of 34–38 °C, along with a relatively high humidity (45 per cent), exacerbating the impact of the heat.

Advertisement

“People are advised to stay indoors during such peak heat hours.”

Precautions: They left their homes at dawn, travelled 2-4 hours, then sat down on heavily packed ground for several hours under the blazing sun. They didn’t have access to water or toilets. “Though the heat is blamed, it was the lack of basic precautions that saw them die.”

Advertisement

Heatstroke: When the air has high levels of humidity along with the heat, the body stops sweating and becomes unable to regulate the internal temperature. This can result in a heat stroke, leading to multiple organ failures and deaths.

Exposure and vulnerability: Heat waves become lethal when the most vulnerable members of the population are exposed to them for prolonged periods. Those who lost their lives were mostly middle-aged to older women in a vulnerable state, exposed to the peak heat for several hours.

Back in Maharashtra, the administration and political parties are taking precautions for upcoming open-air events, likely in response to the Kharghar incident. They are arranging water bottles, mobile toilets, and on-site doctors to attend to emergencies. If we had taken these precautions beforehand, we would not have lost those fourteen lives.

How do heat waves occur?

Heat waves occur when dry and hot air sinks from the upper atmosphere and pushes down towards the surface of the earth. As it descends, the air gets compressed and becomes even hotter, creating a stifling dome of heat. This makes it hard for clouds to form, which means that the sun’s heat can directly reach the ground, making the region even hotter. This is why heat waves often occur on clear, sunny days. This is a typical condition in the Indian subcontinent during April–May. Now we have additional heat accumulating due to climate change, resulting in more intense heat waves.

The arid northwest Indo-Pakistan region, which is home to about 760 million people, is particularly vulnerable to record-breaking heatwaves. During April–May, temperatures frequently exceed 40°C, sometimes leading to scorching heat waves. These events have become more intense, longer-lasting, and more widespread in recent years. These heat waves can be lethal, especially for the elderly and those with preexisting health conditions.

Geographically, the heatwave zone lies diagonally across the Indo-Pak region. In India, the states of Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana lie in the heatwave zone. Between 1971 and 2019, heatwaves claimed about 17,362 lives in India—that is, about 350 per year on average.

How is climate change exacerbating heatwaves?

The increase in these heat extremes is in response to the 1 degree Celsius rise in global mean temperatures due to historical carbon emissions. All these events are projected to intensify further since the commitments from global nations (historical emitters US, Europe, Russia, etc., and currently China, India, etc.) are insufficient to keep the temperature rise from hitting 1.5 degrees Celsius between 2020–2040 and 2 degrees Celsius between 2040–2060. That is not somewhere far in the future. That is not just for our children or grandchildren. Most of us living now will face a doubling of global temperatures in a few decades. While we are reeling under the impacts of that 1 degree Celsius, the grave impacts of doubling are difficult to visualise.

Heatwaves are projected to become more frequent and intense in the future, posing a threat to the growing vulnerable population in the region. In fact, future climate projections indicate an increase of up to sixfold by the year 2060. The region’s largely vulnerable population is expected to reach 1 billion by 2050, further raising concerns about the impact of future heat waves.

Cities are turning into urban heat islands

Cities turn into urban heat islands when buildings, roads, and other infrastructure absorb and re-emit heat, causing cities to be several degrees hotter than surrounding rural areas. During the day, the sun’s rays reach as shortwave radiation and heat the Earth’s surface. At night, the heat escapes as long-wave radiation. While shortwave radiation can easily penetrate through and reach the surface, the longwave gets trapped easily by concrete and clouds.

The high-rise buildings and concrete setup in the cities do not let the excess heat escape during the night. As the temperatures do not cool down, the heatwave continues into the night. Open green spaces and natural environments with trees can help release the heat faster during the night. However, in India, we do not appreciate natural space as much as we appreciate skyscrapers. Add some haphazard city planning, poor architecture and unsustainable construction to it, and the recipe for an urban heat island is complete.

Have a look at the nighttime temperatures in Delhi and its surroundings in the month of May. The difference is stark and stunning—up to 20 degrees Celsius between the city and rural areas. Climate change is aggravating the heat everywhere, but the urban heat islands that trap this heat are our own construction.

Heatwaves, dryness, fires and pollution altogether

The heatwaves in the year 2022 were record-breaking. While the maximum temperature touched 50 degrees Celsius in India, it went beyond 51 degrees in Pakistan. This was a season-long heatwave spanning from March to May. The impact was aggravated due to the fact that the season did not see any thundershowers to bring the temperatures down. The north-northwest states of India saw a rainfall deficit of 70–90 per cent, and this was not expected.

A combination of heatwaves and dry-drought conditions can be deadly, leading to impacts such as widespread fires, crop loss, and water scarcity. The conditions impacted wheat grain size and production. India is the second-largest exporter of wheat, but it had to curtail wheat exports in May 2022 to ensure national food security. The particular dry and stagnant atmospheric conditions also lead to raised pollution levels as the particles from widespread fires and stubble burning remain in the air. We see more of this kind of overlapping extreme weather conditions—known as compound extreme events—in response to changing climate and land use changes.

High temperatures and less water result in more air conditioners for cooling and groundwater pumping for irrigation, leading to increased electricity demand and emissions. This is a vicious cycle where the demand for cooling leads to more heating of the planet. Basically, the impacts of such heatwaves are on the food, water, and energy sectors and derail us from the mitigation and adaptation strategy that we are currently on.

Forecasts and heat action plans to help

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) provides heatwave warnings on a 6-hourly basis for the next five days. These forecasts go to all cities and districts in India, where the local governments prepare a yellow (watch), orange (be prepared), or red (take action) alert based on the severity of the heatwave. The forecasts meant for the next two days have an accuracy of 80–90 per cent, which means that they are reliable. There are heatwave outlooks for the next two weeks and for the season that can help in advance planning.

These forecasts are available in the public domain, and the media often disseminates this information in national and regional newspapers. If your regional media outlet does not do that, call them up. IMD has a FAQ document on heat waves that has detailed information regarding heat wave forecasts and is available on their website.

After the fatal heat waves in 2010, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation developed a heat action plan for the city in coordination with the meteorological forecasts. Community outreach, health alerts, training of healthcare professionals, and efforts specifically targeted at vulnerable groups have helped reduce the impacts of heat stress on the local population. Drawing lessons from Ahmedabad’s Heat Action Plan, several cities and states across the country have initiated their own action plans with the help of disaster management agencies and the health departments. If you are a city or panchayat without a heat action plan, what’s stopping you?

There is no running away from heat

I live in Pune, where the temperatures are generally mild, but during the month of May last year, the heat reached Pune as well, with temperatures touching 40 degrees Celsius. This was also the time after Covid; the schools had just started, and the kids were eagerly pushed to school. The unfortunate part was that kids returned at a time when the temperatures were at their peak and, hence, were exposed to the extreme hot air. By the time my kids reached back, they were almost in a heat-struck situation. We approached the school with the forecasts, and they cut down the school hours to save the children.

Though it was mild this year, Pune saw a few weeks of early heat in April. Since there was no policy in place and since the school management had changed, no precautions were taken. We had to repeat the same sequence of events, with the school cutting down the hours close to the summer vacation.

While forecast-based heat action plans are good, they are not sufficient. We need policies considering the fact that heatwaves are here to stay and intensify. We have sufficient data to identify the regions where the heatwaves are increasing, and we need to have policies in all those places. We need to redesign our cities to have open spaces and trees that help in releasing the excess heat quickly and also act as hubs for shade and cooling down. Integrating a heat emergency plan into the education system and workplace policies can equip individuals to handle heat emergencies and protect their health and wellbeing. India needs a long-term vision where we have policies that help us manage our work hours, public infrastructure, schools, hospitals, workplaces, houses, transportation, and agriculture for heat waves to come.

Advertisement