Dogs have a special place in relating to humans. They collaborate in several activities – herding sheep, leading the blind, fetching game in the hunt, as trackers, watchdogs and companions.

Trainability apart, they anticipate human need, are empathetic and many dog lovers are convinced that the furry friend understands their very speech.

Advertisement

While this belief amuses friends and critics of dog lovers, Emily E Bray, Gitanjali E Gnanadesikan, Daniel J Horschler, Kerinne M Levy, Brenda S Kennedy, Thomas R Famula, and Evan L MacLean, from the University of Arizona at Tucson, University of California at Davis and “Canine Companions for Independence”, a United States-based non-profit organisation that trains and provides assistance dogs, write in the journal, Current Biology, of their enquiry into whether the affinity of the dog to humans has a genetic basis.

That humans are so good at using their minds, the paper says, is in part because humans develop, very early, the ability to communicate and respond to each other. By the time a human child is two-and-a-half years old, the paper says, she is as good as the great apes in manipulating her physical surroundings.

And as for reasoning and communication, she is miles ahead.

The paper cites studies that show that even very young puppies, with negligible experience of human contact, can make sense of human gestures or other signs to locate hidden food — a trait that does not exist in wolves raised by humans, one paper emphasises. And other studies that show that dogs can “follow the handler’s gaze” in a way human babies do, once the intent has been indicated. The origin of this capacity to read signals, whether it arose genetically, has not been adequately researched, the Current Biology paper says. The authors hence carried out trials with a substantial sample, 375 puppies, just over eight weeks old, on a battery of socio-cognitive experiments.

The thinking, they say, was that if the skills of dogs in cooperating with humans are something they have because of biology, then, the traits should be clearly apparent even in very young dogs, and without calling for contact with humans or any training. And, there should be evidence of the ability being inherited. The evolution of traits takes place due to selection.

When some individuals in a group have a feature that confers a survival advantage, those individuals would thrive, doing better than the others, and if the trait were one that is inherited, their progeny would carry it on. Has social cognition in dogs arisen in this way? Well, it is true that some dogs are more socially adjusted with humans than others.

Has this been a survival advantage? As dogs have been bred for ease of handling and being tamed, we could say the trait has been selected. And the third, whether the trait passes on to progeny – this is the question that is to be examined. The trials consisted of three stages. The first, the “warm-up”, was for the subjects to get the idea that there were treats to have in this exercise, hidden in goblets with lids.

This done, a handler held the puppy a little away and equidistant from where two goblets were to be placed.

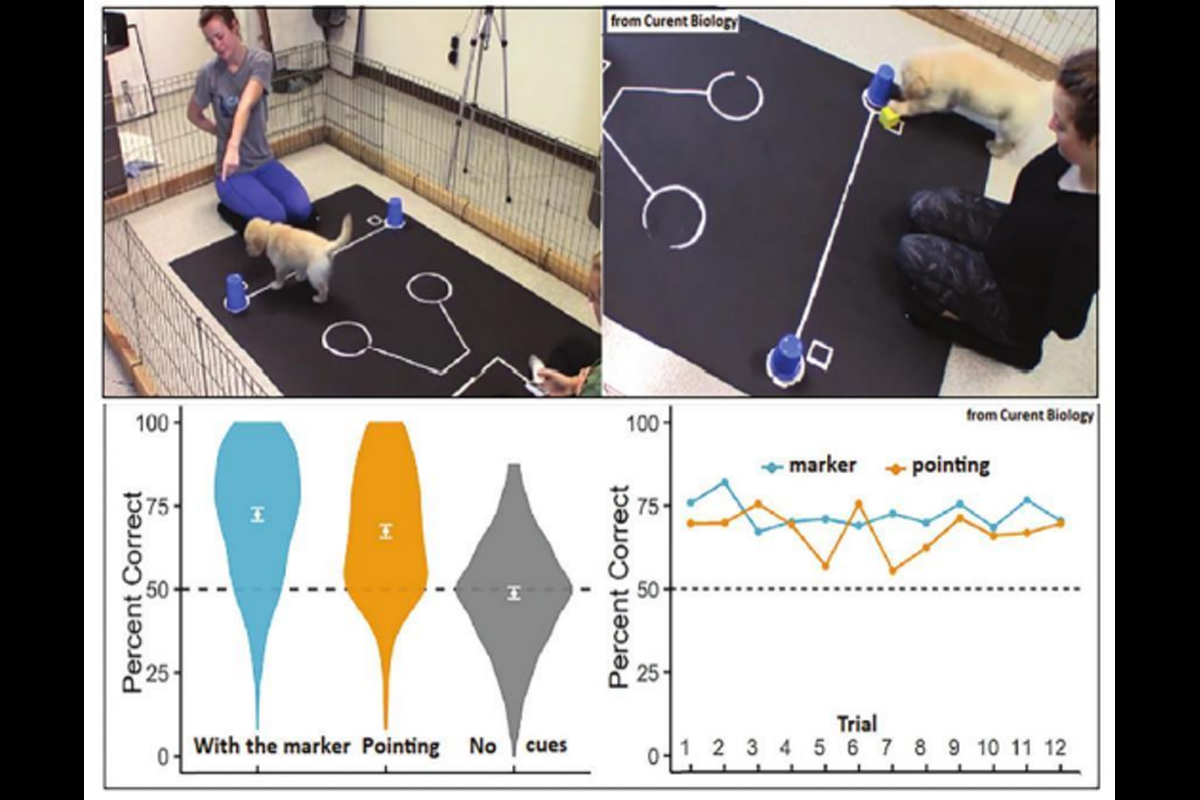

The experimenter then concealed the treat in one goblet and placed the two goblets, some two metres apart, as shown in the picture.

Now was the operative part. The puppy was released, and the experimenter drew the puppy’s attention, made eye contact, and indicated the goblet that had the treat, by pointing, and by turning her gaze to the goblet.

And the puppy was left to find the goblet and the treat.

The second version of this trial was the same as the first, except that this time, the experimenter indicated the goblet not by pointing or her gaze, but by placing a marker, a bright yellow cube, next to the goblet.

In order to eliminate the possibility of the puppy finding the treat by scent, there was a control test of seeing how well the puppy did when it received no cues, of pointing, gaze or the marker.

The second trial was of the human interest, of finding what time a puppy spent looking into the experimenter’s face, or staying within a short distance of her. For this, the experimenter stood outside the experiment area and recited a script to attract the puppy’s attention.

The time for which the puppy looked at her was recorded. She then stepped into the experiment area and the time the puppy spent in proximity to her was recorded. In the third trial, the puppy was set an “impossible” task – the lid on the goblet was fixed, so that the puppy could not get to the treat.

The idea was to see if and for how long the puppy gazed at the experimenter’s face when this happened.

The results were that the puppies did benefit from the pointing, gaze and the marker – they did positively better at finding the treat than when there were no cues.

The picture displays the large areas that correspond to discovery of the treats when assisted by the cues, and the random distribution when there were no cues — which shows that it was the cues that helped in the first two cases.

The same result is displayed as a graph, showing better performance when assisted by the cues. As for the second trial, the puppies did gaze at the human when spoken to spend time with her. And with the “impossible” task, the social gaze was much shorter. Communicative behaviour is hence not there in early development. Next, were the traits inheritable? This was looked at by drawing up a relatedness matrix of the 375 puppies, to work out what proportion of differences in traits could arise from heredity.

In the case of human twins, the paper says, 47 per cent of the variance in cognitive ability can be attributed to genetics.

Among the puppies, 43 per cent of the variation in the pointing trial was found to arise from genetics.

Attention to the experimenter’s face was similarly heritable, but sensitivity to the marker cue was less so, and the ability to communicate, the “impossible” task, was the least.

The paper notes that the studies are valid, as puppies at eight weeks have spent time mainly with other puppies, with little possibility of learnt, human communication. As regards learning with practice, in the tasks, the paper notes that with 375 cases on hand, it was established that performance was the same from the very first trial and did not improve with experience.

The mechanism by which the puppies get this sensitivity is not clear, but this much is — that “dog social skills emerge robustly in early development and differences in these traits are strongly influenced by genetics.”

The paper also notes that there are other species that show sensitivity in reading human gestures and communication. It would be instructive to see how far genetics contributes in these cases.

The study could provide a model for biological bases of cooperative-communicative skills of humans too.