Delhi PWD Minister inspects development projects

During the inspection, Minister Pravesh Verma took stock of three important projects. The first is from Bhoro Marg to Sarai Kale Khan where road strengthening work is going on till the ring road.

It is one of the five markets chosen for a transformation by the Delhi Government. Unlike the rest, it is a wholesale market.

(Photo: SNS)

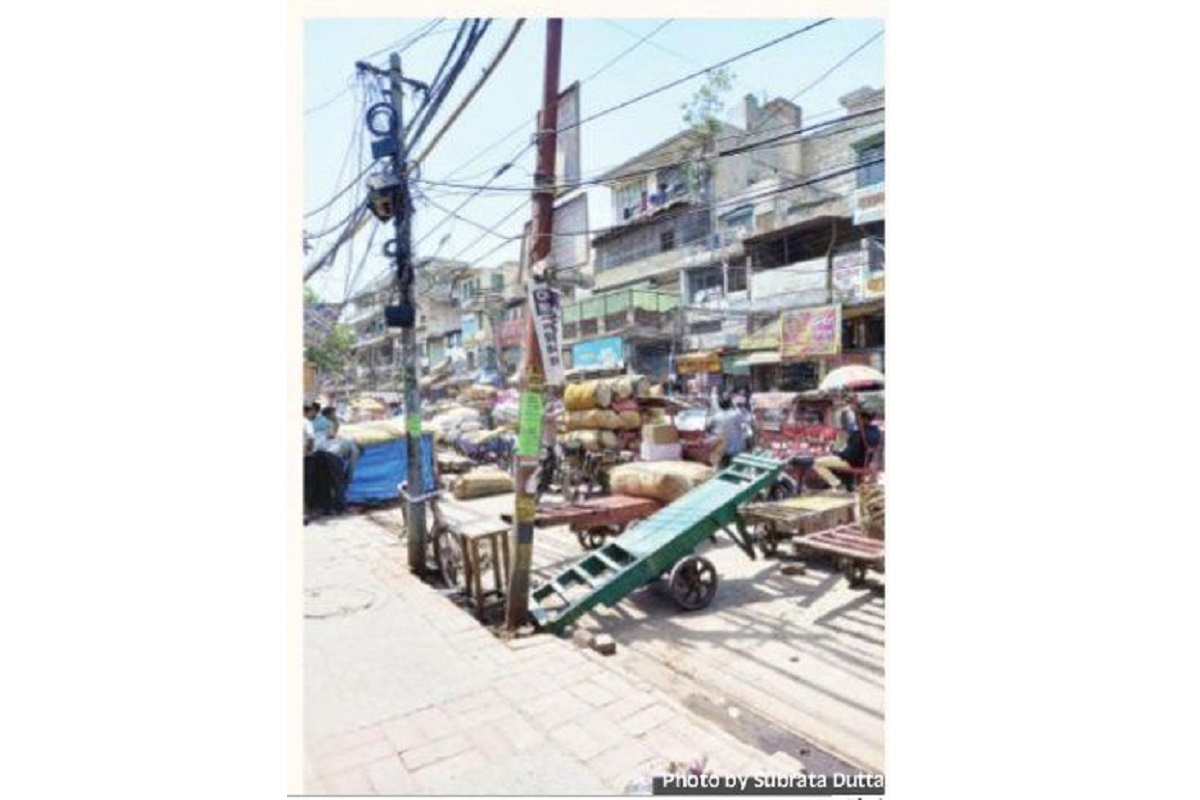

Khari Baoli is apprehensive today. It fears the pains it may have to undergo for its makeover. It is one of the five markets chosen for a transformation by the Delhi Government. Unlike the rest, it is a wholesale market. Its daily turnover may run into hundreds of crores.

If its makeover happens at the speed at which the nearby Chandni Chowk was renovated, it can ruinhuge businesses.

Advertisement

Khari Baoli’sbazaar of dry fruits and spices runs a kilometre from Fetehpuri Masjid-end ofChandni Chowk to Lahori Gate. What it shows to a casual visitor on a cycle rickshaw ride, or ona foot march, is quite deceptive. It has much more business going on in its lanes down the way.

Advertisement

This is typical of Old Delhi bazaars. The Mughal era market is ready for beautification, but not at the cost of its business. For this market, nothing matters more than the daily supply and off-take of its almonds, cashew nuts, raisins, fresh and dry dates, and more, by the quintal, and not just a few kilograms.

The other markets which figure in the Delhi Government’s program to revamp local Markets are Sarojini Nagar, Lajpat Nagar, Kamla Nagar, and Kirti Nagar. These markets are popular markets. In fact, leg[1]ends are woven around their names. People swear by the range of things they can buy at these places.

They will reveal the bargains they made only if they are pressed. Sarojini Nagar market evolved as an answer to Lajpat Nagar. Lajpat Nagar’s popularity was because of women’s cotton suits available in a huge variety and cheap.

Sarojini Nagar, a Government babu colony a few kilometers away, could not afford to sit quietly. Introducing a new feature of “sales promotion” by shouting prices at the loudest, particularly at peak evening hours, its pavement vendors beat Lajpat Nagar in its own game.

The rest is history. While Lajpat Nagar today competes with Karol Bagh and Chandni Chowk in wedding shopping, Sarojini Nagaris a fast-fashion centre. Kamla Nagar evolved into a haunt for Delhi University North Campus students in the late Sixties, because of a coffee house and few book shops.

Population explosion on the campus forced the young and hungry to deeply explore Kamla Nagar and its business grew. Kirti Nagar was a timber market and at first supplied well-designed furniture for the common man.

The Capital’s real estate growth story, in the course of time, unfolded a much larger role for the market. It developed into a major furniture hub for the whole city. Khari Baoli, comparably, is an ancient market, where poor laborers can be seen moving goods on hand-carts. There are clutters of e-rickshaws and cycle rickshaws. The façade of most buildings is losing plaster.

There are open urinals, not seen anywhere else in the city. A jungle of electric and TV cable wires runs through the market. In places, it comes dangerously low. But shops are busy doing business without a blink. Green cardamom, sold at Rs 3200 a kilo in retail markets, is available here from Rs1600 a kilo. Lotus seeds (makhana) can be had for Rs 600 a kilo or less if a big order is bargained for. The dry fruits and spices too are available in a bigrange of prices and quality.

The traders have no time to answer questions on their market’s revamp plans. Their business was affected when the close-byChandni Chowk was “redeveloped,” restricting customers’ access to their shops.

Now they fear they will be ruined if a similar exercise is carried out in Khari Baoli, particularly at the same pace, and marked by long pauses over small issues.

Certainly, they will like it if the wire-jungles disappear from public view, and there is orderly parking for cars of the shop-owners. If the frontal parts of the dilapidating buildings are properly plastered, the market will get an attractive look. Perhaps it will get many more visitors for its fabulous “achaar-murabba” outlets and storehouses of Indian ittar (perfumes). But its traders will likethe whole operation done smoothly, and not continue for years. Otherwise, their customers will forget their shops and search for other options.

Advertisement