Punjab: Union Minister Joshi assures farmers continued dialogue to end deadlock

Punjab Government yet again played a pivotal role in breaking the ice between the Centre Government and farmer unions. Union…

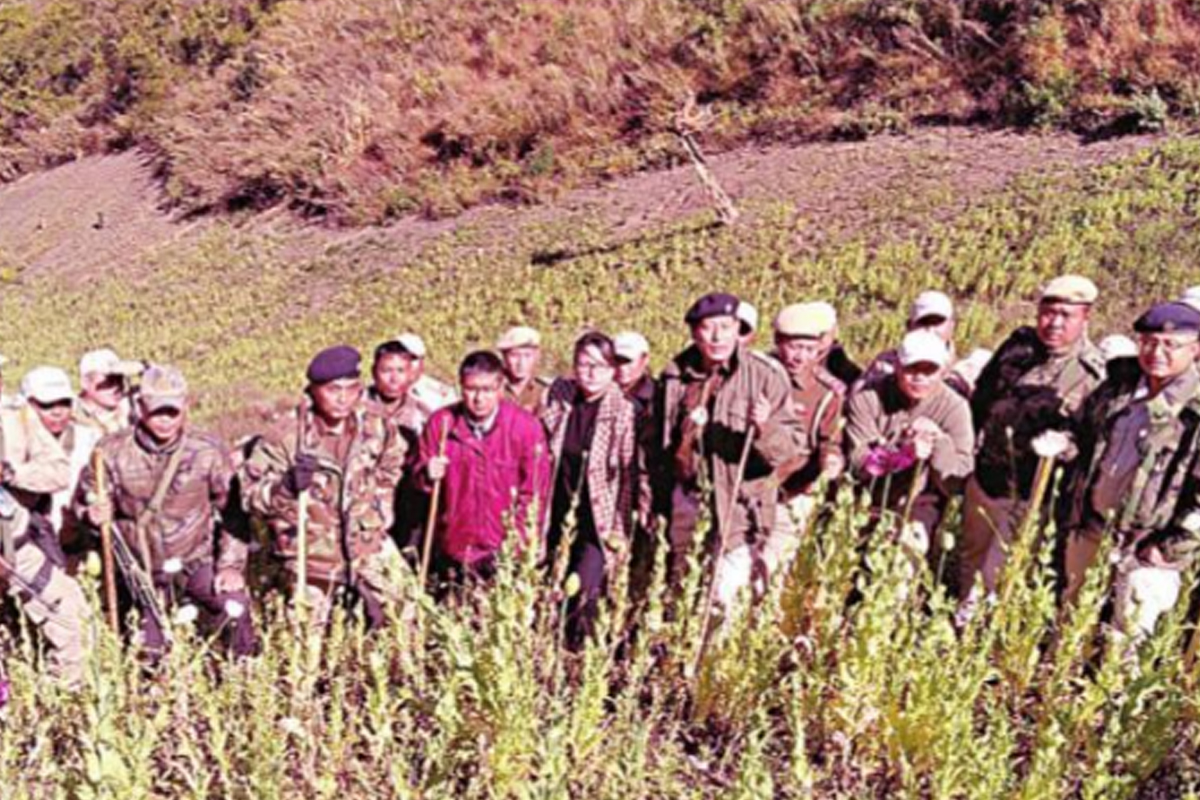

The cultivation of poppy in the hills of Manipur should be taken as a crisis of agriculture

In 2018, a year after he came to power, the N Biren Singh government launched a “war on drugs” to curb trafficking, illicit crop cultivation and consumption. The Narcotics and Affairs of Border department of Manipur Police has been continuously dealing with drug smuggling and arrested 386 peddlers in 2019. In the previous year they reportedly seized 1,21,5273 WY pills from the state. On the other hand, addicts and peddlers are largely dealt with by local community organisations and authorities. Religious organisations and NGOs also bear the burden of the state by establishing rehabilitation centres for drug users and people with other addictions.

It was in the late 1980s and particularly, during the 1990s, that Manipur and other North-eastern states, like Nagaland and Mizoram, witnessed the peak of drug addiction. The addiction of heroin not only destroyed the future of many youths and shattered the dreams of their parents, but the sharing of injection needles among drug users also led to the spread of HIV/Aids, almost to an epidemic proportions.

Advertisement

Interestingly, during the 1980s and 1990s when heroin addiction was at its peak among the youth, it was not poppy but ganja (bhaang) that was largely cultivated. The cultivation of poppy in the hills started in the late 1990s. The shift is largely due to the relatively smaller size of the opium product and lesser price fluctuations, even though the cost of cultivation is larger and more care is needed. Today, however, drug addiction is mainly on WY tablets (methamphetamine).

Advertisement

In recent years, the government has stepped up its efforts to discourage and thwart such cultivation. During winter, the state security forces identify and destroy farms. On 20 November this year, Manipur Police launched a special drive in the Teiseng area and Lanva upstream of Churachandpur district and destroyed 20 acres of poppy cultivation. Another drive was also conducted to destroy illicit cultivation in Ukhrul district the following week.

A person was arrested for attempting to incite violence towards the police team on social media. A university teacher in Manipur was also arrested for criticising the approach of the state government in destroying a year-long cultivation without providing alternatives to cultivators. The official policy of the government has been enforcement — to stop illegal smuggling and peddling — but it has not moved beyond these largely unsuccessful activities.

There is no single factor for farmers in the hills turning to illegal cultivation. However, one of the predominant reasons is the perennial neglect of the hills areas, particularly the plight of farmers. Farming is the principal means of livelihood for most rural hill families. They are small farmers whom technological advancements in agriculture are not helping much.

Technological laggardness is coupled with poor transportation and storage facilities in the hill areas. Unlike Imphal valley and the national highways, which are well-connected, some subdivisional headquarters are still not motorable during the monsoon, let alone the villages. In villages such as Henglep, even seriously ill people have to be carried on bamboo stretchers to reach the district hospital. In such areas, transportation of farm products is costly and timeconsuming, resulting in many perishable foods and vegetables decaying on the way itself.

Farmers also face a lot of hurdles in marketing after overcoming the hill limitations. Rural farmers have to sell their agro-products at a relatively low price to middlemen due to the lack of marketing infrastructure in district headquarters and in the capital city of the state. The women and tribal markets recently constructed in different parts of Manipur are occupied by the relatively well-connected. At Ema Keithel (Women Market) located in the heart of Imphal city, not a single pangal (Manipuri Muslim) or hill woman can be seen, which also means that a vendor license is not given to them.

The absence of cold storage has made farmers sell their products at throw-away prices, else the produce gets rotten. Thus, as one study pointed out, the predominantly rural character of agriculture, which operates under conditions of isolation and makes modern economic methods difficult to penetrate, remains the fundamental challenge in the hill districts of Manipur. Furthermore, lack of modern institutions and infrastructure put farmers in a disadvantageous position when competing with domestic and export markets.

The farmers’ plight is compounded by the growing cost of education. In the hills of Manipur, government schools mainly operate on paper and most have no infrastructure. The teachers, who are mainly from towns, do not attend classes in connivance with village chiefs. In the absence of functioning government schools, private schools fill the gap. The farmers are hard-pressed by the exorbitant fees collected by such schools and other expenses.

Given these circumstances, some farmers turn to the lure of illicit cultivation. There is a worldwide recognition that illicit cultivation of poppy and other such crops is directly linked to rural poverty. The United Nations’ Office on Drugs and Crime recognised that “growing illicit crops often helps small rural farmers cope with food shortages and the unpredictability of agricultural markets”. Despite such economic dependence on illicit crops, however, they are not sustainable in the long term.

In the US, the “war on drugs” is regarded as one of the greatest mistakes of the 20th century. It was fought for a really long time but largely failed. Drug addiction is now taken as a public health crisis, rather than as a criminal justice issue, to help drug users get treatment for addiction.

One way forward for the poppy cultivation problem in Manipur is to take the issue as a crisis of agriculture. To solve such a crisis, the decades-long neglect of the hill areas, in terms of institutions and infrastructure, has to change. Applying redundant laws on hapless farmers will only be an ad-hoc solution.

The N Biren Singh government has often raised slogans like “go to the hills” and “go to the villages”. Recently, Singh claimed that the “go to the villages” initiative has been replicated by the Government of Jammu and Kashmir as a “back to village” programme to bring about equitable development in that state.

Words aside, it is time for the Manipur government to reinvigorate their much-touted slogan and address the needs of farmers in the hills.

The writer is assistant professor, Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

Advertisement