PM Modi on 3-day visit to 3 states–MP, Bihar, Assam–from Sunday

According to the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), the Prime Minister will visit Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Assam from February 23-25.

On the basis of the historic Assam Movement, there have been calls for re-visiting the National Register of Citizens with 1951 as the base year.

Photo: SNS

During our high school days, we witnessed the historic Assam Movement and for a full academic year, all educational institutions across the state were closed. A series of protest-demonstrations took place in even the remotest parts of Assam and almost everyone, at least in the Brahmaputra Valley, got involved in the uprising against alleged illegal immigrants from East Pakistan and later, Bangladesh.

Among the slogans that we used to chant in public meetings, processions or cycle rallies, the year 1951 figured prominently. The primary demand was to detect and deport every unauthorised migrant who had entered (and taken shelter) in Assam after 1951. We were made to understand that once the illegal citizens were deported, a golden Assam (popularly termed “Sonar Asom”) would be a reality.

Advertisement

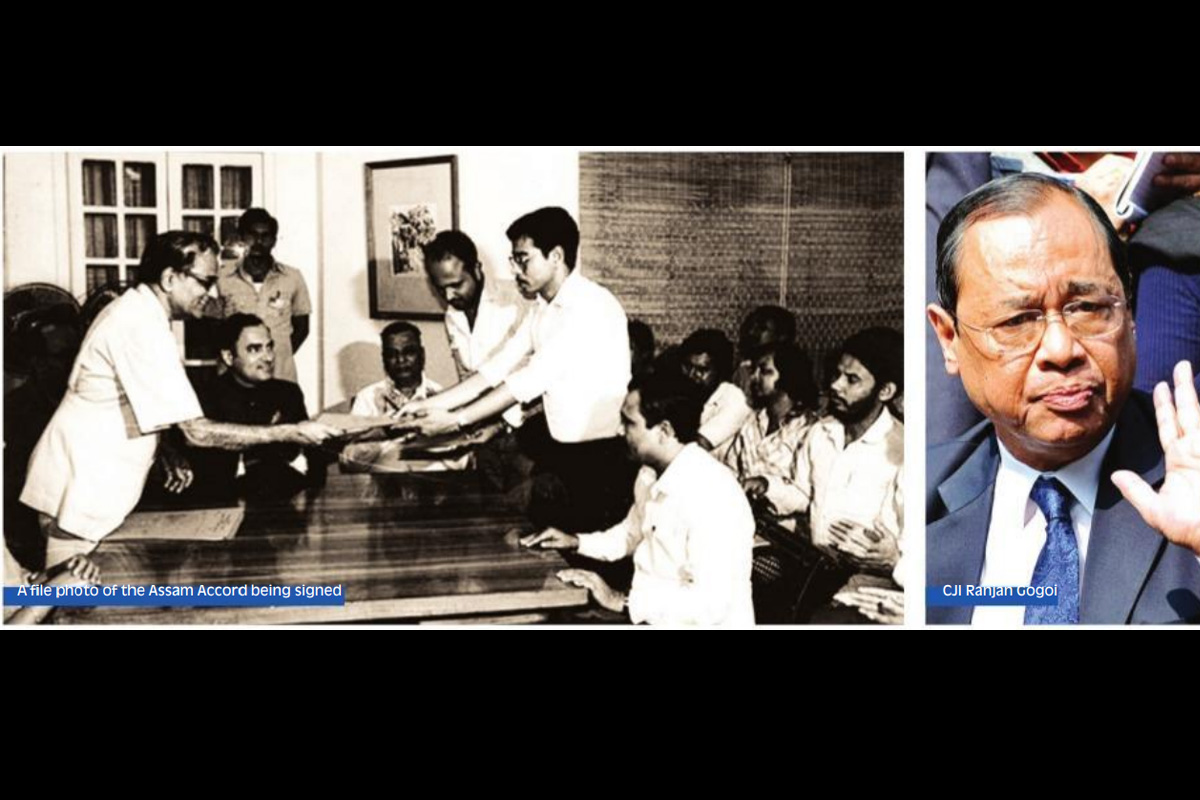

The six year-long Assam agitation from 1979 to 1985 culminated with the signing of a historic memorandum of understanding between the Union government in New Delhi and leaders of the All Assam Students Union and Asom Gana Sangram Parishad. They signed the Accord in the presence of then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. But they had to compromise on the base year for the detection of illegal immigrants.

Advertisement

The Accord put responsibility on the Centre to detect and deport all immigrants who had entered Assam after the midnight of 24 March 1971. In other words, the agitating leaders agreed to accept all residents of Assam prior to that date as legitimate Indian nationals. They, however, succeeded in guaranteeing constitutional safeguards for the indigenous communities of Assam in the Accord.

The Asom Gana Parishad was born after the culmination of the Assam Movement. The regional political party even came to power in Dispur for two tenures. But the problems of illegal immigrants, who were alleged to be slowly shrinking the resources for indigenous people, continued to persist. Both the Congress and AGP failed to address the issue as their leaders lacked the necessary political will. Finally, civil society groups had to knock on the doors of the judiciary for identifying locals and illegal “foreigners”.

Following an appeal from Assam Public Works, the Supreme Court ordered to update the National Register of Citizens in Assam on 17 December 2014. The apex court also monitored the exercise that involved over 50,000 Assam government employees along with temporary technical workers for all these years. It barely warrants mention that the sole purpose of updating the NRC was primarily to prepare a list of authentic Indian citizens.

It was mandatory for every resident of the state to apply in prescribed forms for including their names in the updated NRC. More than 3, 30, 27, 660 applications were received between May 2015 and 31 August 2015 and those were scrutinised by the government employees concerned. If a resident could prove that his/her or their ancestors’ names were included in 1951 NRC, voters’ lists and other relevant government documents issued prior to the midnight of 24 March 1971, they were made eligible for inclusion. After two drafts of the NRC in Assam, updated with the prescribed cut-off date of 25 March 1971, the final one was released on 31 August this year, as the apex court denied any more time for re-verification of the list. Mentionable here is that both the governments in New Delhi and Dispur wanted reverification in some selected localities as it was apprehended that many illegal immigrants had enrolled their names in the list with fake documents.

But the apex court turned down the plea on 23 July, on the grounds that the State NRC Coordinator, Prateek Hajela, in his report to the SC had said “in the course of consideration/adjudication of the claims, reverification to the extent of 27 per cent has already been done”. It created major disappointment among the local people, however, that wasn’t visible in the public domain.

The final NRC excluded 19, 06,657 people, who might be declared “foreigners” after an exhaustive judicial processes. However, they are allowed to appeal within 120 days in the quasijudicial Foreigners’ Tribunals, whose numbers are 300 across now the state. Till then the Bharatiya Janata Partyled governments, both in Delhi and Dispur, have assured no action against those excluded individuals.

Meanwhile, leaving aside some, most of the mainstream Assam-based organisations expressed dissatisfaction over the final NRC alleging errors with the exclusion of indigenous families and inclusion of illegal “foreigners”. The All India United Democratic Front, Communist Party of India and a few others came out with supporting statements for the Assam NRC arguing that it was an outcome of intensive labour and could be considered a first step to solve the burning issue.

More recently, the Chief Justice of India also came out with a public statement that the NRC could be a base document for the future on which Assam can define its claims. CJI Gogoi, who is incidentally a native of Assam, stated that the NRC is not a document of the moment. He also commented that dealing with the NRC was an opportunity to put things in their proper perspective.

CJI Gogoi, while criticising a section of media for irresponsible reporting on the NRC, cautioned that frequent shifting of the cut-off date (to detect illegal “foreigners” in Assam) is like playing with fire. His comment had a reflection on rising demands for updating the NRC with the base year of 1951, as that is applicable across the country.

It may be mentioned that a petition filed by an umbrella body of several indigenous organisations (Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha) advocating for 1951 as the cut-off year in updating the NRC is still pending in the SC. The ASM petition was sent to a Constitution Bench in December 2014.

However, a strong voice of dissatisfaction with the present form of the NRC was raised by APW, claiming that it would only help illegal immigrants to get their names enrolled in the beneficiary list. APW chief Abhijit Sharma publicly asserted that the complete reverification of the NRC (with the new cut-off year being 1951) has become the need of the hour to safeguard the future of Assamese people from the invasion of Bangladeshi settlers in Assam. Reposing full faith in the SC, Sharma made it clear that they were completely dissatisfied with the final outcome and would revisit the apex court soon with papers and documented facts related to it.

Sharma was also vocal against Hajela, who was recently transferred to Madhya Pradesh and was the sole authority in spending nearly Rs 1,600 crore during the exercise. “There is a strong need for the audit of all government money spent and also the IT used in the process, which must be executed by internationally acclaimed organisations. A huge chunk of money, which was released by the authority concerned to various organisations for necessary IT assistances, should be thoroughly audited,” said Sharma.

The ruling BJP also declared that it would go to the apex court with an appeal for reviewing the NRC. Assam BJP mastermind Himanta Biswa Sarma categorically stated that many genuine Indians were kept out from the NRC and hence they would not accept the outcome. The saffron party’s regional ally, the AGP also came out with a statement that the final NRC could not bring relief to the indigenous population of Assam.

The AASU, which initiated the anti-foreigners movement in the 1980s, also expressed dismay over the final NRC. Similarly, the Muslim Kalyan Parishad and Asom GariaMaria Yuba Chhatra Parishad claimed that the final NRC is not acceptable to them as it contains huge anomalies. Commenting that the indigenous people are not happy with the final NRC, they have demanded its re-verification

The influential anti-influx group Prabajan Virodhi Mancha also termed the process of screening citizenship in the NRC as faulty. PVM convener and a senior Assamese lawyer practicing in the SC, Upamanyu Hazarika supported the demand for identifying illegal “foreigners” in Assam with the cut-off year being 1951. He even urged everyone in the state to support the ASM petition seeking a review of the cut-off date.

Given the historical scenario, it is nothing unusual to put 1951 as the base year but one can understand the complications around it. It may be hoping against hope, but nonetheless, everything is possible in a democracy like ours.

(The writer is the Guwahati-based Special Representative of The Statesman)

Advertisement