Security beefed up in Ayodhya after arrest of terror suspect in Haryana

Security in and around Ram Temple and other places have been increased after a suspected terrorist and resident of Milkipur was recently arrested from Faridabad in Haryana.

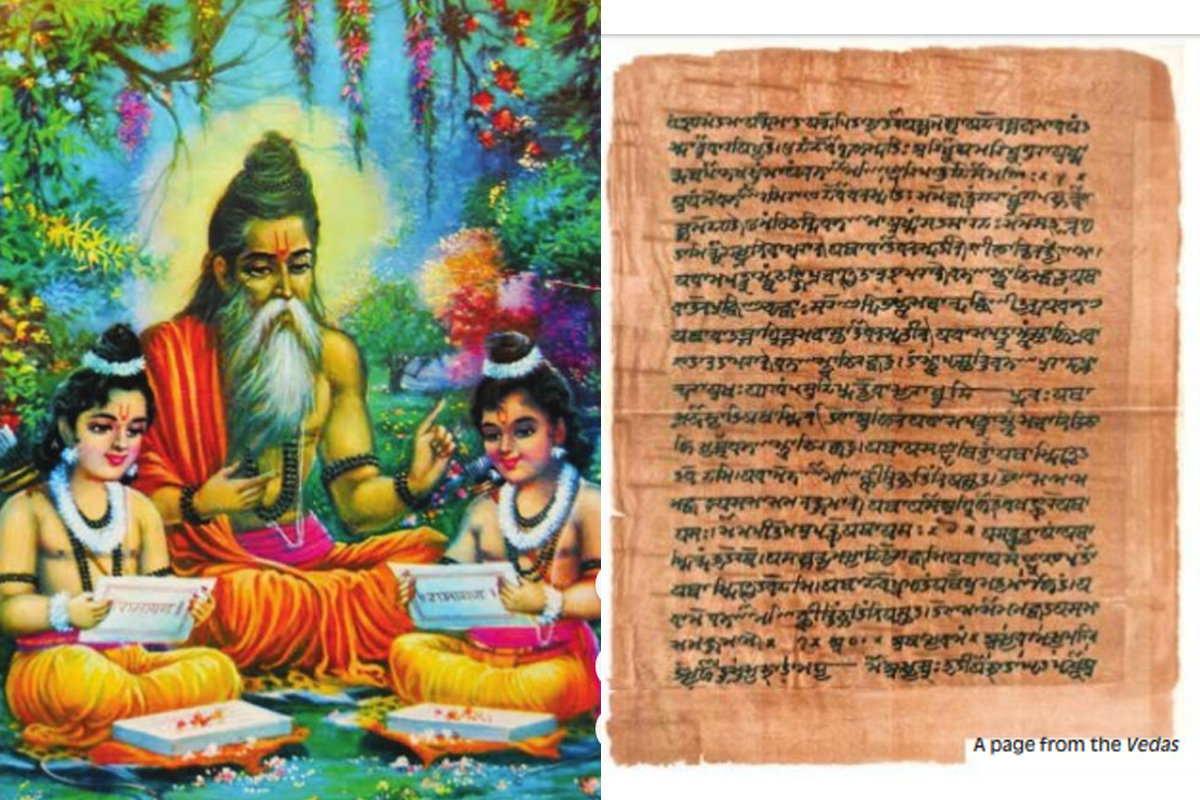

Hindu traditions and religious practices have remained unaltered from the time of their very inception thousands of years ago, when religious texts were originally composed.

Representation image (Photo: SNS)

I marvel at the unchanging path of religions. Having taken over the management of my family’s 80-year-old Radha-Krishna temple in Haryana’s Simbla, I have had many thoughts on Hinduism’s journey: like its genesis, which took place in a different millennia. Today, we practice each custom the way it was followed in the distant past. It is this singular aspect, which fascinates me the most.

If a pandit conducts a havan — a Sanskrit word, where offerings are made to a consecrated fire, twigs from a mango tree lights the flames. When the pandit seeks God’s blessings, he utters the word swaha and sprinkles some ghee unto the flames which cleanses the surrounding evil vibes. When prasadis offered, it is not unusual to serve it on banana leaves, which is associated with Lord Vishnu.

Advertisement

The peepal tree is revered, and prayers with lamps are offered to Lord Brahma, who is at the apex of the holy trinity of Hinduism, comprising Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu. On Saturdays, these lamps, placed at the base of the peepal tree, must be lit only with mustard oil.

Advertisement

The shani tree, which owes its holy significance to the Mahabharata, is also prayed to on Saturdays. None of these trees have been identified for religious rituals in recent times. They, too, go back thousands of years. Behl leaves are offered to Lord Shiva on Mondays. He is believed to protect the Earth when there is no moonlight and the planet is plunged into darkness.

If we take one festival as an example, like Janmashtami, which celebrates Lord Krishna’s birth, a cradle is placed near the altar depicting the infant Krishna. Butter, curd and milk are offered to the deity because, as a child, Krishna was associated with these milk products.

Pandits or Brahmins in the past traversed through different places and lived on offerings that people provided. In present times, the only difference is that pandits either live in a temple complex or in a house. It is common to see a panditlinked to a particular temple; so, their movements are limited now as compared to the past. To view the larger picture of a panditslivelihood, it rests primarily on the offerings of people who visit a temple to pray. The pandit also visits houses to conduct prayers on certain auspicious days which encompass marriages and other events. Satyanarayan Puja, which is conducted by a panditin someone’s home, is believed to bless the family with happiness and prosperity.

In the 5th century BCE, a sage named Valmiki wrote the Ramayana, an epic about the prince of Ayodhya, Rama, and his wife, Sita, and his exile and return. The return of Lord Rama from exile came to be known as the festival of lights, or Diwali, which is associated with lighting lamps and bursting firecrackers. It is a scenario manifested with joy and revelry. Different types of crackers have evolved in recent times; but, we must remember that Valmiki’s creation of the festival remains unchanged.

We are in the pujaseason and a reflection of Durga Puja evokes another sphere of our amazing diversity, going back to yet another incredible period of time. MaDurga was a demon-slaying Goddess, who signifies the ethos of preserving good over evil. The Goddess is worshipped on Durga Ashtami and Astra Puja, the most auspicious day of puja when weapons of the Goddess are worshipped. This puja goes back to the time of the Hindu classic text, between 400 and 600 BC.

Notwithstanding Valmiki, sages and rishis in ancient times often lived in solitude, in the foothills of the Himalayas, and composed hymns, originally in Sanskrit, in praise of the Almighty.

The Vedas form the genesis of Indian literature and go way back to 1400 BCE. Prayers from excerpts of the Vedas are recited by pandits and we are reminded that similar religious incantations in our country have continued uninterrupted and steadily over the centuries and millennia.

Over 2,000 years stand as a testament to the fact that our religious practices will not change. Indeed, this reflects Albert Einstein’s space-time, which explains that we may carry out what we wish to in the space around us, but time cannot be brought back. We may note and adhere to the past, but that is all. Thousands of years of old religious practices remain unaltered, unchanged and constant.

Advertisement