On the metaphysics of alienation

In metaphorical terms, alienation stems from a lack of place or disavowal of community. Kalpna Singh-Chitnis communicates this alienation with grace and sincerity.

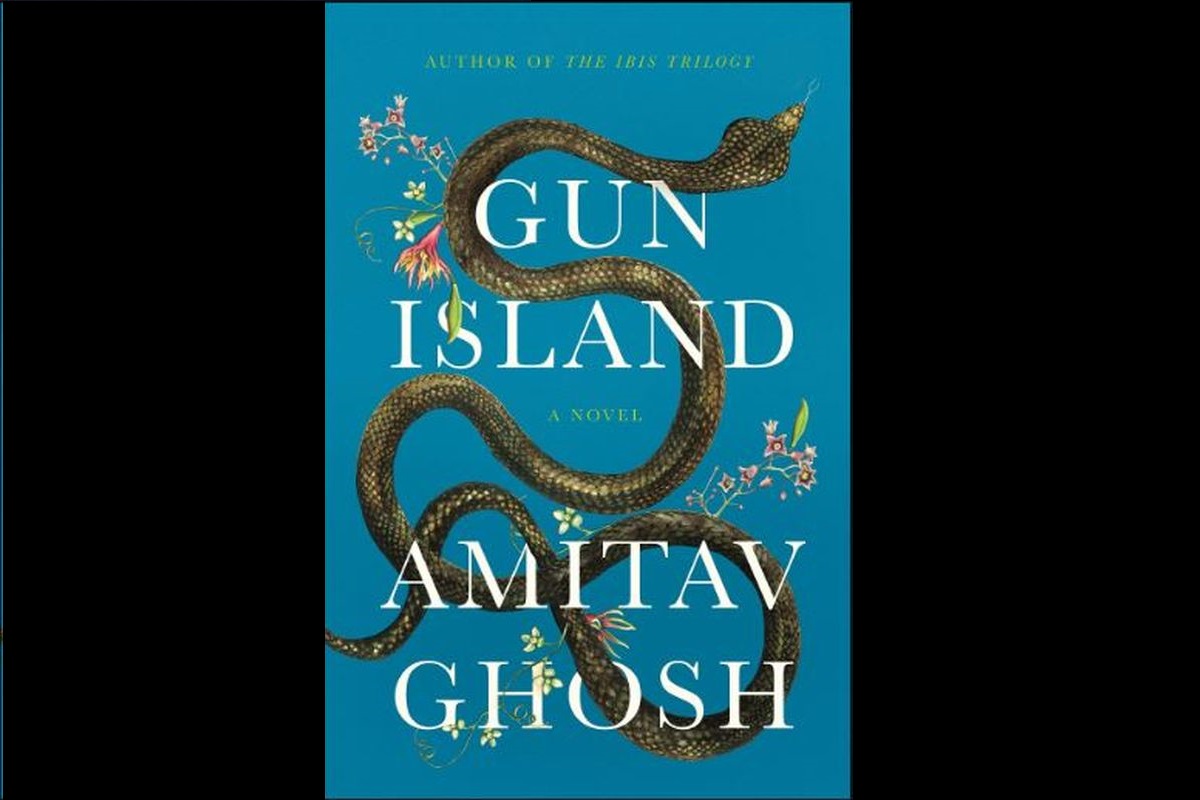

Gun Island is engrossing and almost reads like a whodunit, thus reiterating Ghosh’s talent as a master story teller and a craftsman of words. It is amazing how he can thread his ideas about climate change, ecological disasters, crossborder migration and global movement of refugees in search of a better life elsewhere all together in his narrative… A review

( SNS Photo)

In 2016, Amitav Ghosh had published a book of non-fiction called The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. Analysing how climate change has reversed the temporal order of modernity and how it is no longer possible to exclude this dynamic even from places that were once renowned for their distinctiveness, the author questions: “Can anyone write about Venice any more without mentioning the acqua alta when the waters of the lagoon swamp the city’s streets and courtyards?

Nor can they ignore the relationship that this has with the fact that one of the languages most frequently heard in Venice is Bengali: the men who run the quaint little vegetable stalls and bake the pizzas and even play the accordion are largely Bangladeshi, many of them displaced by the same phenomenon that now threatens their adopted city ~ sea level rise. Behind all of this lie those continuities and those inconceivably vast forces that have now become impossible to exclude, even from texts.”

Advertisement

The reason for beginning this review with such a long quotation is that in the present novel Amitav Ghosh is actually elaborating on these ideas along with the use of history, myths and transnational migration that is plaguing our world at present. So what is Gun Island about? The first person narration of the novel begins with Dinanath Dutta aka Deen who is a rare book dealer in Brooklyn, New York and who during a visit to his birthplace Kolkata accidentally finds himself in the Sunderbans chasing the myth of Bonduki Sadagar (Gun Merchant) and Manasa Devi, the goddess of snakes and poisonous creatures. As the mythical story goes, during the reign of the Mughal emperor Jahangir, the Bengali merchant Bonduki Sadagar had started on a voyage to avoid the rage of Ma Manasa. On the way he was captured by Portuguese pirates who chained him and sold him off as a slave.

Advertisement

A merchant named Iliyas purchased him. After that they try to do business in various islands with exotic names but face either epidemics or hardships of various kinds. In the end when the Gun Merchant arrived in Venice, Manasa Devi spots him. Feeling terrified of her he returns to Bengal and comes to the Sunderbans to build his own brick sanctuary. Cut to the present time. When Tipu takes Dinanath to this place he finds that the panels of the temple still recount the legend of the Gun Merchant’s feud with goddess Manasa. Syncretically all the local people still sing hymns orally and recite from the panchali about this legend as it was apparently dictated by the merchant that they could not be written down.

After that a string of occurrences take place when Tipu is bitten by a king cobra. He survives but is often attacked by strange premonitions which link the ancient world with the modern, the east with the west, and human with the nonhuman. He often hallucinates and predicts unnatural events taking place in the human and non-human world. Yearning for a better life in the west, Tipu and his friend Rafi leave the Sunderbans through the help of touts and human traffickers. After a lot of perilous journeys together, they get separated and eventually Tipu lands up in Venice. The story of his illegal migration in search of a better life elsewhere is so topical that it doesn’t read like fiction at all.

Through his story Ghosh asks important questions about what migration and movement means, how human rights issues that are plaguing many countries are actually problematising the idea of closed borders and xenophobia and destroying the peace and tranquility of people who are especially residing in the Global South.

The other major player in the story is Cinta, who is a brilliant academic from Venice with a long celebrated career and a tragic personal history. It is through her that Deen manages to land up in Venice where he grapples with both the mysterious and the brutally real in equal measure. As a very knowledgeable professor, Cinta is in many ways Deen’s emotional and intellectual mentor. At one place she tells him not to ‘underestimate the power of stories’ because ‘there is something in them that is elemental and inexplicable.’

At one point early on in the novel Cinta berates Deen for rubbishing a folk tale in a jatra performance as “superstitious mumbo-jumbo.” She says, “Why do you use all these religious words like ‘superstitious’ and ‘supernatural’? Don’t you know that it was the Catholic Inquisition that put these words into currency?” When Deen objects that it is all semantics, she replies that “the whole world is made up of semantics and yours are those of the seventeenth century. Even though you think you are so modern.” Ghosh also gives us a series of increasingly uncanny episodes that seem to dissolve the borders of the human and the non-human.

Ghosh states that issues like climate change and accelerating impacts of global warming resulting in ‘ecological refugees’ had worried him since the time he was writing The Hungry Tide but now it seemed to him that those problems have far wider implications. He admits that this subject figured only obliquely in his earlier fiction. Though certain characters like Piya, Kanai, Nilima Bose, Moyna, Fokir’s son Tutul (now called Tipu) reappear in this novel as well, it can in no way be considered a sequel.

The characters move on in time and place and actually add to Ghosh’s discussions of the hard life in the Sunderbans and how many events of the novel, which seem magical, can be explained by rationality and logic. Piya the cetologist explains why the Gangetic dolphins behave in an unnatural manner and land up near the shore to die. We are also told how a sudden tornado destroys all human habitation on its path.

Going back once again to a statement expressed in The Great Derangement: “This then, is the first of the many ways in which the age of global warming defies both literary fiction and contemporary common sense: the weather events of this time have a very high degree of improbability. They are not easily accommodated in the deliberately prosaic world of serious prose fiction.” So we read about a wildfire raging in Los Angeles; when Deen goes to the sea beach with the Italian lady Gisa and her two children then their pet dog fetches something from the waves in his mouth and it happens to be a yellow and black snake that is usually found further down south in warmer waters; again a very poisonous spider known as loxosceles reclusa is found in Cinta’s apartment in Venice; woodworms and black beetles destroy buildings.

All these signify that global warming has seriously affected non-human existence also. In an interview Ghosh had reiterated that all that he wrote was the reality of his life and many other people spread across the planet and it was in no way ‘speculative.’ At the end of the novel the protagonist Deen realises that he has to accept both the rational and the mysterious side by side.

Readers of the Ibis Trilogy often felt that though Ghosh moved across continents and easily traversed through different terrain, the burden of history or historical research in those novels was quite heavy on the casual reader. Though he cannot do away with historical and literary references in some sections of this novel too that range from Tarantism, the Aztecs to the Catholic Inquisition, such heaviness is more or less absent.

Here Ghosh moves easily from the early historical to the modern era with ease, making his characters feel essentially located in different geographical terrain ranging from the Sunderbans to Venice to Los Angeles. He tangles myth with fact to bring home to the readers that the world as we know is in the grip of unprecedented change and if we ignore it then our doom is close at hand. He had earlier mentioned that “the climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination” and through this novel he tries to prove it.

Gun Island is engrossing and almost reads like a whodunit, thus reiterating Ghosh’s talent as a master story teller and a craftsman of words. It is amazing how he can thread his ideas about climate change, ecological disasters, cross-border migration and global movement of refugees in search of a better life elsewhere all together in his narrative. His earlier refusal to accept the Commonwealth Prize has been adequately compensated by the recently given Jnanpith Award to him for his outstanding contribution to English literature. He really deserved it.

( The reviewer is Professor of English at VisvaBharati University )

Advertisement