Nayanthara reveals how she fell in love with Vignesh Shivan

Superstar Nayanthara, who made her Hindi cinema debut with the Shah Rukh Khan-starrer box-office juggernaut ‘Jawan’, has recollected how she and her husband, Vignesh Shivan fell in love.

The ubiquitous staircase has captivated the imagination of both mainstream and avant-garde filmmakers for generations and they have used it as a site to either articulate a play of passion or to accentuate the expression of power, tension and drama between characters differentiated by gender, ranks and hierarchy.

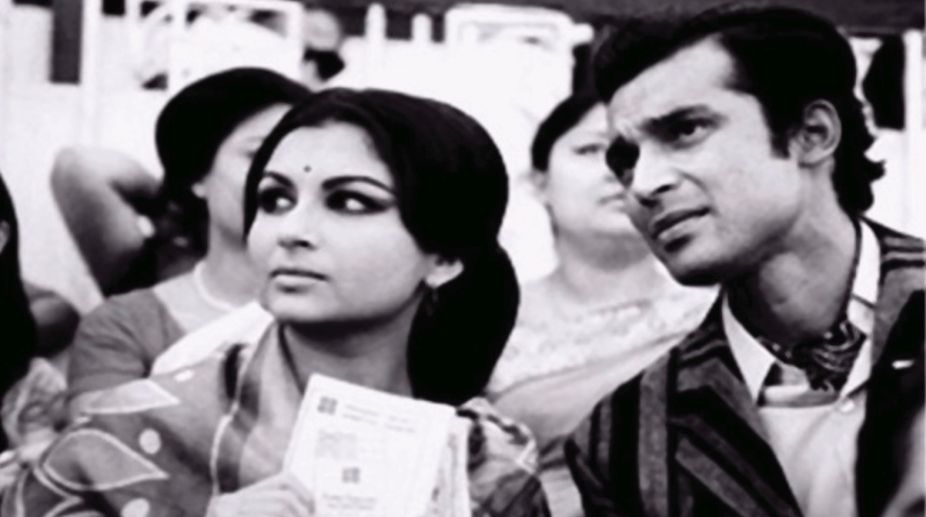

Satyajit Ray’s Seemabaddha.

‘Stairs are very photogenic.” Alfred Hitchcock’s sardonic remark made before Truffaut wasn’t a hyperbole. Hitchcock’s oeuvre is a testimony: at least ten of his films have stairways that dominate either the climactic scenes or act as potent symbols in the course of the narrative. In both cases the pictorial aspect of the simple architectural feature mutates into something sinister and dark to heighten inner contradictions and flaws in a character’s personality.

The master of horror isn’t alone in his fascination, though. The ubiquitous staircase has had captivated the imagination of both mainstream and avant-garde filmmakers for generations and they have used it as a site to either articulate a play of passion or to accentuate the expression of power, tension and drama between characters differentiated by gender, ranks and hierarchy.

A flight of stairs has also been used as an aesthetic tool to mark a moment of history or to emphasise socio-cultural conflicts.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Consider for instance the poignant use of the staircase in Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 masterpiece Battleship Potemkin. In what is celebrated as the ‘Odessa Steps’ sequence, Eisenstein utilises a flight of steps to heighten the dehumanizing effects of imperialist forces by gradually building up the tension through diverse camera angles along with a shifting variety of shots ranging from long, medium and close-ups: A series of conflicting perspectives that underscore the doom that awaits the people at the face of the rampaging soldiers marching down the ‘Odessa Steps’.

Amidst the bloodbath and chaos, a mother climbs up the stairs with the body of her dead son in her arms — a defiant image of a subtle protest that offers a hope of resistance to the future mutineers for a just cause.

Ascent against all odds, however, isn’t always a cause of celebration. The climb up can be ironical, if not amusing, when pertinently contextualized. In Satyajit Ray’s Seemabaddha (1971), the lead Shyamalendu returns home to share the news of his promotion to his wife.

But a power outage has stranded the elevator and to access his luxurious apartment he has to use the staircase. Shyamalendu sets off cheerfully, covering a number of steps of the staircase that connects the different floors, but eventually his pace slows down from exhaustion— a wry representation of the cost of the futile rat-race in which he has willingly participated in.

Access. A defining word in relation to a staircase. For entering either a palace or a simple heath, a place of worship or a venue of passion often involves covering the vertical space as represented by a flight of steps, a momentary journey that carries both metaphorical and symbolic meanings.

Such a voyage acquires a further dimension when the emphasis is on the cosmic passage between life and death, a journey that from a believer’s perspective could end up either in paradise or hell depending on one’s karmic cycle.

What accounts for a formally simple structure to achieve such nuanced meanings? In her essay ‘Stairways of the Mind’ Juhani Pallasmaa writes: “…The staircase is simultaneously a stage and an auditorium. It is also a vertical configuration of the labyrinth with consequent associations of vertigo, and getting lost.”

Filmmakers who explored such allegorical aspects in relation to a staircase owed a debt to German expressionism, the influential artistic genre which reshaped the aesthetics across different art forms and took the lead in evoking sinister and cynical images.

Impacted by the movement, many émigré filmmakers in Hollywood used the staircase as a leitmotif and turned it either into a site to heighten the psychological tension of a warped character or a zone to play out the tension of a crime.

Let’s recall Edgar G. Ulmer’s masterpiece, The Black Cat, a film in which a spiral steel staircase acts as a defining emblem to frame the evil as embodied in Poelzig, a priest whose darkness is veiled by a mask of civility. In another German classic, Pandora’s Box, the staircase with its serrated shadows exemplified the cutting nature of the killer’s mind.

Two decades later, Film Noir also employed the staircase as a zone to play out dark and emotionally saturated drama. A classic example is the final scene of Billy Wilder’s 1950 epic Sunset Boulevard where in the climactic scene the silent-era actress Norma Desmond is seen descending down a grand staircase in response to the staged call of ‘Action’ which she takes as real (she, in the meanwhile years, has lost touch with reality) and thereby pauses to claim her happiness to be in films again and rounds up the declaration with the telling words: “Alright Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up”. Here the flight of stairs acts as a metaphor of Norma’s descent into a life of total insanity.

Taking the cue from these lessons, Hitchcock weaved his repertoire of horror and complexities by relying often on a staircase as a motif to either emphasise escape as in Shadow of a Doubt, or to bring out an inherent psychological dimension as in the fear of heights in the film Vertigo.

In Psycho, a film with varied psychological nuances, the staircase becomes a leitmotif and recurs to situate differing emotions. Take for instance when on the trail of a suspect we see detective Arbogast hurrying up the staircase leading to the entrance of a building.

Once inside the room he confronts another staircase, but this time around he ascends it with apprehension without the earlier bounce in his walk. The audience is prepared for a tension ahead and it bursts forth when Norman, a deranged man who had killed his mother and now dresses up as her, jabs the detective’s face with a knife and sends him tumbling down the very stairs that he had climbed with suspicion. The outer and the interior staircases thus become two disparate zones to present two different moments of a character’s fate.

*

Beyond the socio-psychological aspects, staircases are also utilised in building salient love sequences. In James Cameron’s Titanic the wooden staircase acts as an unobtrusive and yet a recurrent background to dramatise the critical moments of the narrative between the two lovers differentiated by their class and positions.

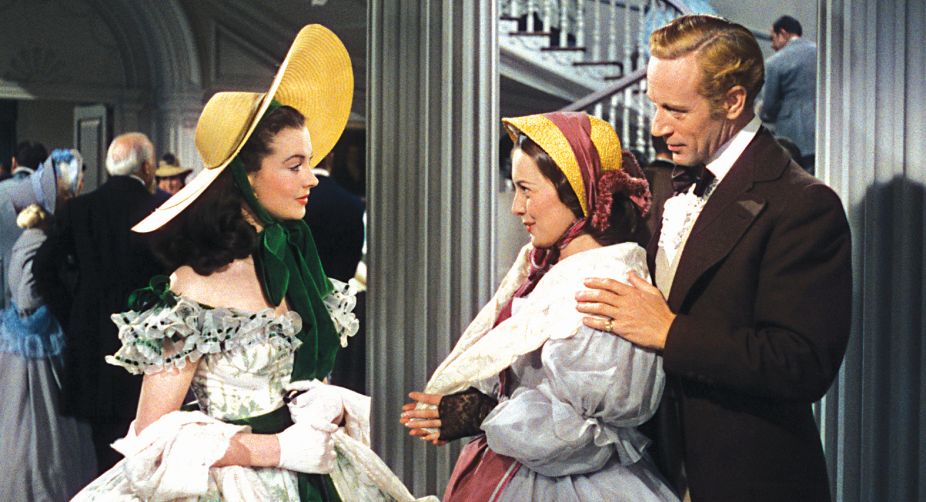

Depiction of a charged romantic moment fraught with tension and passion also comes alive on a grand red-carpeted staircase in Gone with the Wind. Here, the descent and the ascent both act a binary to frame two conflicting emotions. In the first we see Scarlet walking down the flight of steps with a dejected look.

In that mood of gloom she gets into an argument with Rhett Butler who eventually resolves the tension and then in an act of controlling gesture takes her in his arms and walks up the staircase with a now compliant Scarlet.

When love is involved then dreams or daydreams naturally dominate the visual vocabulary. In the context of Hindi cinema one such striking moment is the song sequence ‘Ghar Aaya Mere Pardesi’ in Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (1951).Clad in a white costume Rita leads the thief Raj up on a staircase – an emancipating journey for Raj under the behest of a pure soul like Rita’s.

One can read such ascent as the mark of liberation for a character. Inversely, directors often underscore a character’s moments of hopelessness and despair by showing him or her walking down a stairway, hands on the banister, their pace either unsteady or lethargic.

However, in Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Neeta’s descent exhibits none of the clichéd pain and anger usually expected of a character after a traumatic experience. Moments before this poignant scene Neeta has discovered her lover’s deceit.

Regardless of the pain and humiliation of knowing that he is in love with her own sister, Neeta walks down in slow measured steps without any tears or restlessness. Her reaction is of grace and inner grit, twin aspects that bestow on her a solemn dignity. The sound of whiplash in the background acts as a heart-wrenching crack on the audience.

There cannot be any standardised modes of depiction through either symbols or gestures. Many a time depending on the director’s perspective, and demands of the narrative, the visual idiom changes.

Take for instance Shekhar Kapoor’s Bandit Queen (1994), a quasi-biopic on the infamous but legendary women dacoit, Phoolan Devi. In one scene, we see her rushing down a flight of stairs with spring steps to meet an aide. The news from the messenger acts as a body blow: her gang has been neutralised by the police. In the subsequent frame we see her ascending the same staircase, but looking vulnerable and defeated, her face shorn of any bravado.

Running down a staircase to greet a lover is a typical moment in mainstream Hindi cinema. The rush, the emotion, the desire compounds when the character is meeting an estranged or a dying lover regardless of the social and marital status. Such was the case with Paro in both versions of the hugely successful film Devdas. In both Bimal Roy’s 1955 version and Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s 2002 edition, the staircase acts as the virtual bridge connecting, even if momentarily, Devdas with Paro, a communion that remained impossible in their mortal lives.

Conjoining two different set of impulses with a staircase in view comes alive in the song ‘Na Main Dhan Chahoon Na Ratan Chahoon’ in Vijay Anand’s Kala Bazar (1960). While Raghuvir’s mother and family sit about a deity singing a song that speaks of the need eschewing earthy treasures, we see her son, a black marketer on a staircase, his hands brimming with the spoils of his trade.

His hesitant pauses on the steps, the surreptitious climb up the steps, his inner conflict for having strayed and deceived his mother ~ all act as a catharsis that would eventually lead him to move away from his identity as a black-marketeer. Such a nuanced depiction of a staircase within one’s home is lacking in the popular and commercial Hindi cinema.

More often than not the private staircases in many films act as markers of opulence of the owner and are deployed more as a spectacle than any symbolic utility. In Mr. India (1987), the villain Mogambo’s grand ‘durbar’ had a flight of stairs to his throne whereas in Hum Aapke Hain Kaun..! (1994) and Hero Number 1 (1997) the magnum internal staircases give the audience an idea about the wealth the characters own.

The staircase thus becomes a symbol of economic mobility and dominance. It not only sets apart the haves from the have-nots, but also creates a circle of inner dominance as often exemplified by a father or a dominant figure standing at the head of a staircase looking down on his kin with both authority and a feudal mindset.

One can recall hundreds of Hindi films where a curved staircase rises up from the drawing room. And it is used to underscore the confrontation between the different agents of patriarchy — the typical ‘father-son’ conflicts in Hindi cinema.

Have staircases lost their functionality and metaphorical presence in an age of chic buildings and high-rises where elevators and escalators are the preferred modes of vertical commuting? Artists, however, always find a way to extend a symbol’s potency.

In the hands of new filmmakers, stairways have continued to be a central focus in many films and with interesting variations. A quick survey would include, the use of the ‘Penrose Stairs’ (also known as the impossible staircase because it seems to turn into itself with no end) in the film Inception – an apt image for a movie that involves dreams.

The perpetual ascent and descent is also the marked feature of Jim Henson’s film Labyrinth that uses a staircase that echoes M.C. Escher’s iconic drawing of never ending stairs. In the asylum scene in Shutter Island, the staircase again returns to evoke the chaos and confusion and the eventual descent in to madness by the main character.

This gentle reminder from Michelangelo perhaps is the most apt conclusion: “My soul can find no staircase to Heaven unless it be through Earth’s loveliness.”

Amitava Nag is a writer, film critic and poet based in Kolkata

Shiladitya Sarkar is a writer, painter and art critic based in Mumbai

Advertisement