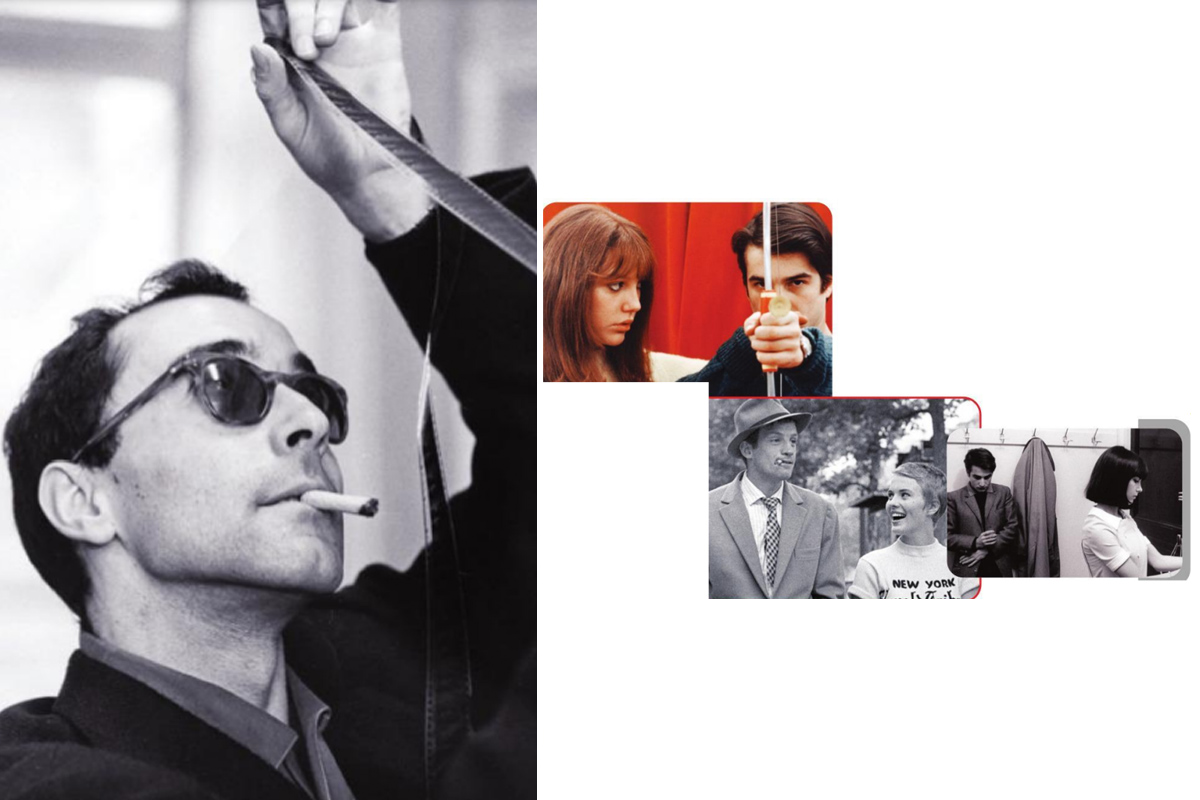

Imagine Jean-luc Godard walks into a bar, orders a shot of absurdity, and serves it to us in a cinematic chalice. Godard, the French New Wave’s enfant terrible, has left an indelible mark on the cinematic landscape, wielding a camera like a surrealist’s paintbrush and crafting narratives that defy predictability like a cat dodging raindrops. From his groundbreaking debut, Breathless, to the audacious political statements embedded in Weekend, Godard’s oeuvre forms a tapestry of complexities, where every frame is a puzzle piece waiting to be deciphered. Born on 3 December 1930, in Paris, Jean-Luc Godard initially aimed for advanced mathematics at Lycée Buffon. However, the allure of the cinéclub scene led him to a cinematic passion, diverting from his academic path. After a failed baccalaureate exam in 1948, he returned to Switzerland, explored modern art, and faced strained familial relations. Successfully completing the baccalaureate, Godard returned to Paris in 1949. Although he initially enrolled in ethnology, he later abandoned formal studies for a deep dive into cinema. Rejected by IDHEC (The French Institute of Cinema), he honed his skills at Cinématheque Francais and Ciné-club Quartier Latin, forming lasting bonds with fellow cinephiles, including Francois Truffaut and Jacques Rivette. Their routine of consuming multiple films daily became a means of escaping their lives, encapsulated in Godard’s words, “The cinema screen was the wall we had to scale.”

THE FRENCH NEW WAVE AND GODARD

Advertisement

Jean-Luc Godard stands as a vanguard figure within the French New Wave, a cinematic movement that emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s. At the heart of this movement was a group of young, rebellious filmmakers, including Godard, Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol and Jacques Rivette, who sought to redefine cinema and break away from the conventions of traditional filmmaking.

Godard’s influence on the French New Wave is profound, characterised by a departure from classical narrative structures and a rejection of established cinematic norms. One of the defining features of Godard’s approach was his innovative use of jump cuts, a technique that involved abrupt transitions between scenes, challenging the smooth continuity prevalent in classical cinema. In addition to his experimental editing, Godard was known for his unique narrative structures.

His films often lacked a linear plot, opting instead for a fragmented and episodic approach. This departure from traditional storytelling allowed Godard to explore themes of existentialism, alienation and the complexities of human relationships.

Godard’s visual style was equally revolutionary. He embraced handheld cameras, natural lighting and on-location shooting, moving away from the controlled environment of studio filmmaking. This approach not only added a sense of immediacy to his films but also reflected a desire to capture the spontaneity of life.

Politically engaged, Godard used his films to critique contemporary society and challenge the status quo. Weekend and La Chinoise are notable examples where Godard explores Marxist ideologies, consumerism and revolutionary fervour, mirroring the social and political upheavals of the 1960s. Godard’s influence extends beyond his directorial work; he played a crucial role in shaping the auteur theory. Embracing the idea that a filmmaker’s work reflects their personal vision and thematic preoccupations, Godard’s films became a canvas for his intellectual musings and artistic experimentation.

GODARD S INCLINATION TO START FROM SCRATCH

A pioneer of the French New Wave, Godard’s cinematic oeuvre is a kaleidoscopic tapestry, each film a unique brushstroke in his avant-garde canvas. Breathless (À bout de souffle), his debut feature, serves as a cinematic manifesto.

The film not only introduced the audience to Godard’s audacious style that eschewed traditional storytelling but also signalled a departure from the polished productions of the time. Godard ushered in a new cinematic vernacular, employing jump cuts to disrupt the flow of scenes, giving the film a rhythm that mirrored the impulsiveness of its characters.

The film’s unscripted, improvisational feel was a departure from the meticulously planned productions of the time, marking a paradigm shift in film aesthetics. Pierrot le Fou continued this trajectory, showcasing Godard’s penchant for experimentation with colour, composition and narrative structure.

The film’s vibrant palette and surreal narrative underscored Godard’s commitment to pushing the boundaries of cinematic expression.

The film’s uninhibited blend of romance, violence and existential musings showcases Godard’s ability to seamlessly integrate disparate elements into a cohesive and thought-provoking whole. His collaboration with cinematographer Raoul Coutard, characterised by handheld shots and a documentary-like immediacy, further solidified his reputation as a visual trailblazer.

As Godard delved deeper into his filmography, works like Weekend exemplified his embrace of politically charged storytelling.

The film’s infamous long take of a traffic jam and its surreal narrative detours underscore Godard’s commitment to challenging traditional storytelling norms.

This film, a scathing critique of consumerism and bourgeois society, demonstrated Godard’s ability to infuse his cinematic creations with profound social commentary. The use of long, uninterrupted takes, coupled with surreal and grotesque imagery, created an immersive experience that challenged the audience to confront uncomfortable truths.

La Chinoise reflected Godard’s engagement with radical political ideologies, exploring the intersection of Marxism and youthful idealism. The film’s distinct use of colour, stylised visuals and ideological debates showcased Godard’s ability to weave complex themes into the fabric of his storytelling. Through these films, Godard didn’t just tell stories; he used cinema as a medium for exploring the intellectual and emotional landscapes of the era.

In examining Godard’s films, one encounters a filmmaker unafraid to experiment with form and content, using the medium to provoke intellectual and emotional responses. The juxtaposition of highbrow intellectualism and pop culture references in Contempt or the self-reflexivity in Masculin Féminin demonstrates Godard’s ability to weave complex themes into the fabric of his storytelling.

The author is a journalist on the staff of The Statesman.