Exploring women’s roles behind and beyond the camera

Regretfully, not too many are aware of these early women filmmakers, as their work is rarely screened or even referred to by the media.

Although one of the most powerful writers in Indian literature, her works have seldom made it to big screen, barring a few notable exceptions.

Photo: SNS

Mahasweta Devi was born into cinema because she was born into the family that produced one of the greatest filmmakers in India —Ritwik Ghatak. But her interests lay in writing, editing her own journal for tribal people, and short stories and novels. Her powerful stories about the dispossessed along with her activism on their behalf have made her one of the best-known, and most frequently translated, of India’s authors. She passed away on 28 July 2016 in Kolkata.

Even though several films have been adapted from her works, the stalwarts of Indian cinema shied away from translating Mahasweta Devi for the silver screen. Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ghatak, Tapan Sinha and Ajoy Kar did not make any of her works into a film. Neither have Shyam Benegal, Ketan Mehta or Basu Bhattacharya. Why is that so? Is it because it is difficult to convert her incisive writings into film? Or because those filmmakers were not so acquainted with her works to conceive of a film based on any of her writings? Maybe, they felt her stories wouldn’t appeal to the general populace in big cities because they dealt mainly with the marginalised of society.

Advertisement

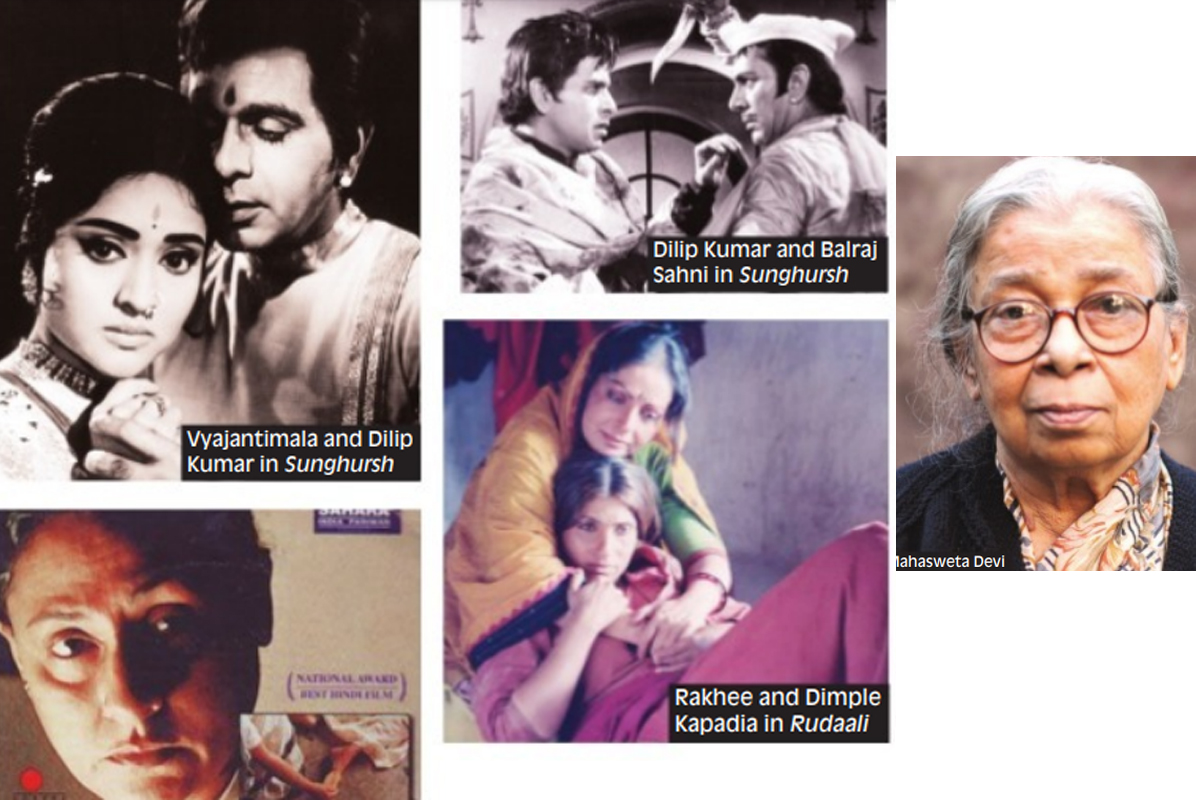

There are exceptions of course, but they are few and far between. Among filmmakers in India, the three exceptions are HS Rawail, who made Sunghursh (1968) a period costume drama based on Mahasweta Devi’s historical fiction Laili Aasmaner Aina; Govind Nihalani who adapted her famous novelette Hazaar Churashi-r Maa in a Hindi film called Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maain 1998, and Kalpana Lajmi’s adaptation of the short story Rudali to the film Rudaali (1993).

Advertisement

Sunghursh, produced, directed and scripted by Rawail, had an incredible cast and crew. Shakeel Badayuni wrote the lyrics, which were set to music by Naushad while Gulzar wrote the dialogues with Abrar Alvi. The film’s star cast was led by Dilip Kumar and Vyjayanthimala as the star-crossed lovers with Balraj Sahni, Sanjeev Kumar, Jayant, Ulhas and Sapru in negative roles, supported by Sundar, Deven Verma, Durga Khote, Sulochana, Padma Khanna and Iftekar all of who did justice to the responsibility they were given. The story of Laili Aasmaner Aina was written much before Mahasweta Devi had stepped into her tribal milieu but still had a social agenda. Her works in fiction were often based on history and this was no exception.

The story had all the ingredients for a lavishly mounted period costume drama. Set in Banaras, the fast-paced film portrays thugs, who were a terror in Northern India in the 19th century. They mostly belonged to priestly families but under that disguise, would rob unsuspecting pilgrims. Rawail, loyal to the original story, addresses the looting that goes on at pilgrim centres in the name of faith. The film demonstrates how the ritual of sacrifice is misused for personal gain and how men compromise love for spiritual virtues — issues that are relevant even today.

Nihalani’s Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa perhaps comes closest to the original story. But he becomes self-indulgent by extending the original in an attempt to give it a contemporary flavour, which does not work at all and spoils the statement it was trying to make. The director suddenly took a time leap into contemporary India, showing the mother of “1084” committed to activism to help those Naxalites who were tortured and imprisoned during the movement. This shifted the focus and became discordant. He also “resurrected” the character of the husband played by Anupam Kher, which struck the wrong note. It did not appeal to the audience either as a mainstream or off-beat film and died a quiet death. Jaya Bachchan, perhaps not familiar with Mahasweta’s Bengali writings, despite being a great performer, somehow retained her charisma as a star.

Another classic novel named Rudali was adapted by Kalpana Lajmi into a Hindi film. Professional mourning has a long tradition in parts of India and Rajasthan in particular. Before the affluent dying man actually dies, he is left uncared for and neglected, often left to sleep in his own excrement. But once he is dead, the family gives him the grandest of funerals as an elaborate and ostentatious statement on its so-called power, fame and wealth within the village or small town. Mahasweta Devi’s primary focus is the portrayal of the community life of Ganjus and Dushads, who form the majority in the Tahad village in the original story.

Though Rudali is a novelette, its powerful story covers a range of issues such as abject poverty, the caste system and Indian funeral practices as well as the role of women in a strongly patriarchal society. Lajmi’s film remains loyal to the spirit of the original but fails in execution, presentation, approach and treatment. She chooses two glamorous actresses of Indian cinema to play the mother and daughter, respectively — Raakhee and Dimple Kapadia, whose starry glamour remains undisturbed despite the no-make-up look Lajmi invests them with. This defeats the very purpose of the film and story’s strong statement.

The music by Bhupen Hazarika imposes Assamese folk music on the Rajasthani ambience but it works well. But too many songs make it a musical and hinder the film’s political statement. The male characters are equally important, as exploited and marginalised as their women are, when placed in the larger canvas of the social structure ridden by caste restrictions and taboos, and Lajmi gives them adequate space. Rudaali, the film, is an independent piece of work by Kalpana Lajmi while Mahasweta Devi’s Rudali, the story, is another independent piece of writing.

Of the Bengali adaptations and the two small Doordarshan efforts by filmmaker Buddhadev Dasgupta, namely Arjunand Choli Ke Peeche in Hindi, the less said the better.

Sanat Dasgupta made a feature film in Bengali called Janani adapted from Mahasweta Devi’s story. It was one of the earliest films featuring Roopa Ganguly. It was about a girl born in adom family but since she was fair-skinned with light eyes, when babies in the neighbourhood began to die, her own clan labelled her a “witch” and cast her out. That film too bit the dust.

Mahasweta Devi made significant contributions to literary and cultural studies in the country. Her empirical research into oral history as it lives in the cultures and memories of tribal communities was the first of its kind in India. Her powerful, haunting tales of exploitation and struggle have been seen as rich sites of feminist discourse by leading scholars. Her innovative use of language has expanded the parameters of Bengali as a language of literary expression, by imbibing and interweaving tribal dialects.

Advertisement