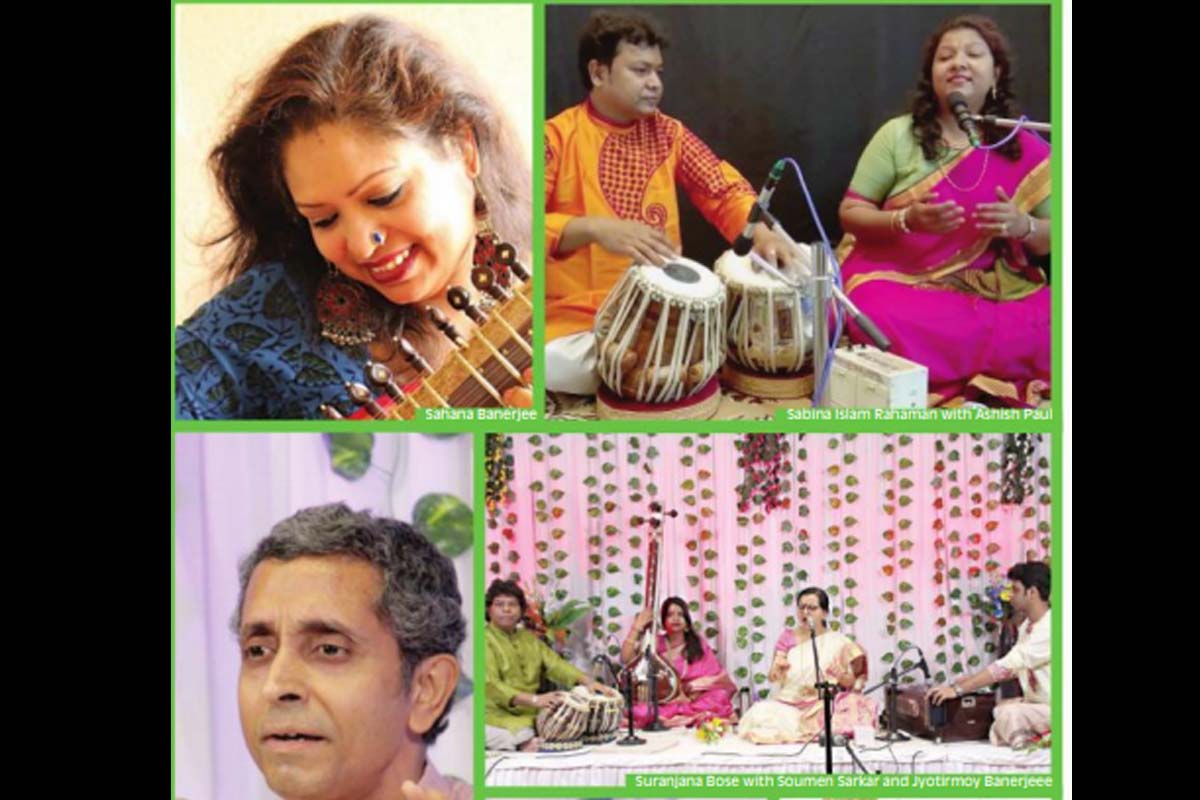

Kalakar Arts, a United Kingdom based organisation operating under the guidance of vocalist Chandra Chakraborty, recently hosted an online event on Facebook featuring two women artists par excellence. It was interestingly designed with intermittent chats during live recitals.

The opening session saw Agra gharana exponent Sabina Mumtaz Islam Rahaman reminiscing her days of initial training by her father Janab Nurul Islam and later with Ustad Jainul Abedin, Pandit Sunil Bose, Vidushi Subhra Guha and Pandit Vijay Kichlu. She also discussed how, under her gurus’ guidance, she imbibed the aesthetics of modifying the forceful gayaki of her gharana to suit a female voice.

Advertisement

To prove her point, she began with an elaborate nom-tom alap in Gara, a rarely heard raga. Her slow ektal khayal traversed the well-sequenced vistar, behlawa and taans displaying different grains before turning to drut teental studded with fast-running taans. Her next choice was a famous composition in raga Nat Bihag called Jhanjhanjhanjhan payal baaje, replete with delightful layakari, bolbaant and taans.

Later, a seasonal Hori set to medium-paced deepchandi tala led to a thrilling tappa in Khamaj. Ashish Paul’s responsive tabla helped enhance the beauty of the presentation. In the final session, sitarist Sahana Banerjee belonging to Rampur Senia gharana, began with a brief aochar in raga Basant and went ahead to play a medium-paced gat studded with taans.

During her chat with Chakraborty, she admitted that her first love is vocal music because her mother Chhabi Banerjee was a vocalist. Later, father Pandit Santosh Banerjee initiated her to sitar. As a result she was encouraged to adopt vocals in sitar, but gave importance to tantrakari even while playing compositions meant for vocal music. To elaborate, she played raga Yamans teental bandish, Main vari vari jaaun and showed how the taan-based mukhda blended instrumentalism beautifully.

The composition was decorated skillfully with fast-paced taans of different varieties.

She concluded in a lighter mood set by raga Tilak Kamod. The brief introduction delightfully covered three octaves and enhanced the meandering gait of the raga. After a deepchandi-based composition, she concluded with a fast teental.

All these short but sweet pieces were sensitively supported by Amit Banerjee’s tabla.

Reviving lost values

Shrutinandan, the musical kingdom of Pandit Ajoy Chakrabarty, recently organised its third consecutive annual thumri festival. The first and second ones were held at Rabindra Sadan, Kolkata at a grand scale, but this year due to the pandemic situation, it was streamed live from the Guru Jnan Prakash Ghosh Sanctum within the Shrutinandan premises.

The motto of the festival remains “Ras bhav rang, thumri ke sang”.

It is true that the essence of rasa (sentiments), bhav (expression) and rang (colouration) go hand in hand in thumri. Chakrabarty is striving to revive and rejuvenate this essence by holding these festivals with much pomp.

He knows that introducing lay listeners to classical music appreciation is quite challenging.

Moreover, even the most renowned vocalists as well as their seasoned listeners are not always able to follow the rich lyrics of genres like dhrupad and khayal, let alone predominantly literature-based idioms like thumri, kajri, chaiti etc. Thanks to the modern education system, the Hindi-speaking belt is as ignorant of the spirituality governed by culture, seasons, seasonal festivals, rituals, relationships (with or without social sanctions) and dialects of the Ganga-Yamuna region – the birthplace and playground of Indian classical music and especially thumri.

In thumris, raga, the intangible king, reigns supreme with its intrinsic rasa, the mood which is another intangible but empirical subject. Hugely influenced by their joint impact, even erudite vocalists often undermine the importance of the sahitya of bandish or the lyrics of compositions – the only medium which actually defines the tangible beauty of the raga, at times by crossing the boundaries of its inherent mood.

This tangible world, obviously, is much more interesting because it portrays age-old Indian culture, with its spiritual, ritual, social, familial and moral values that still exist in the remote rural pockets of this vast land.

Maybe, to cling on to the old heartwarming values, even the top-ranking instrumentalists resort to sing the lyrics of compositions meant for vocalists. And even if they don’t sing, their playing techniques emote the vocalised form with the same stress points, the same way of bending notes and by using the same phraseology. To emphasise the importance of the sahitya or the melodic literature of Hindustani classical music, such thumri festivals will go a long way.

The handpicked artists of the evening mesmerised audiences with colourful presentations.

Young vocalist Atri Kotal sang a thumri in Mishra Khamaj. Her confident and melodious rendition was beautifully accompanied by Soumen Sarkar and Jyotirmoy Banerjee on tabla and harmonium respectively. Asmita Mitra was on tanpura. It was followed by the recital of khayal and thumri exponent Sanjukta Biswas, a worthy disciple of Vidushi Subhra Guha.

She presented compositions in rarely heard ragas. Commencing with a thumri in Pancham se gara, her next performance was a seasonal Hori in Sindhura Kafi and she concluded with Bin piya nindiya na aaye ho Rama, a famous chaiti.

Deep emotions flowed through all her renditions which were sensitively supported by Ashoke Mukherjee’s tabla, Gourab Chatterjee’s harmonium and Paramita Roy’s tanpura. Khayal and thumri singer Shantanu Bhattacharya, the sole male participant of the evening, began his rendition with a thumri in Pilu and followed it up with another thumri in Khamaj that turned into a bandishi thumri.

After yet another thumri in Manjh Khamaj, he concluded with the dadra called Koyeliya gaan thaama ebar. Sudhir Ghorai (tabla), Chatterjee (harmonium) and Mita Bhattacharya (tanpura) provided him excellent support.

As the final artist of the evening, yet another renowned khayal and thumri exponent Suranjana Bose too chose to begin with a thumri in Pilu but with a different composition (Dhoom machi hai) that celebrated the season. Her second piece was a chaiti and she concluded with Jiyara na maane mora, a dadra in Bhairavi.

The emotion charged with a languid and melodious approach remained her hallmark. Sarkar (tabla) and Banerjee (harmonium) once again rose to the occasion by providing superb support. Vocalist Anol Chatterjee introduced all the singers and accompanists and conducted the programme in his melodious style.

The writer is a senior music critic.