Shabana Azmi reveals she was hesitant to star in ‘Fire’ due to its homosexual content

Shabana Azmi reveals she was hesitatant over starring in ‘Fire.’ Even though she liked the script, she was hostile towards starring in it.

(Photo credits: Twitter)

Vast areas of land get submerged under water due to flood. Land, property, cattle get eroded and crops are destroyed. “Why do we sow seeds if the flood is going to destroy it anyway?” asks young Dhunu to Basanti, her mother. The mother reasons with her emphasising that sowing crops is the ‘karma’ one must continue doing even though life may be hard since there is probably no other option. “Work is religion to us,” she tells Dhunu, “Hard work is all we have.” In a separate scene in another mother-daughter private, intimate moment Basanti tells Dhunu that the latter’s father was drowned in the flood because he was not brave enough.

It is bravery, she continues which rotates life and revolves it round the mortal destinies of life and death, the natural calamities and the heavenly misfortunes. The intellectual pretences of the middle-class elite may find this resigning to fate contrived yet the reality of large sections of the ‘Bharat’ within the ‘India’ is to succumb to it simply because of the unnerving repetitiveness of the same.

Advertisement

Set in Dahgaon Kalardiya in Assam’s Chhaygaon, Rima Das’s Village Rockstars (Best Feature Film, 65th National Film Awards, 2017 and India’s official entry in the foreign language film category at the Academy Awards in 2019) shows life in a placid yet idyllic village where the basic amenities are rare. The children go to government schools and spend most of their time under the vast expanse of sky in the lap of nature.

Advertisement

The serene divinity of the environment probably fosters them to remain simple and still pursue individual dreams. Yet, this story is not the typical fairytale about struggles, human-conflicted misfortunes, hurdles laid down on the beaten track climaxing to transcendence. There are moments of glory though they are almost private and personal.

There are sombre heartbreaks as well which in spite of being intimate also resonate at a universal level. But one thing that stands apart is the apparent nothingness of the narrative progression and the serene stillness of rural Assam which acts as a lush grand narrative itself much larger than the mortal existence of individuals. In a sense Village Rockstars makes one remember Haobam Paban Kumar’s Lady of the Lake (2016) which also has a docu-fictional element in its form, a tranquil stagnancy of camera and an absolute flat narrative tension.

Both of them may qualify as Indian ‘Slow cinema’ which is important since in the mainstream media culture this type of cinema is absolutely a non-vogue thing to try out. That director Rima Das is almost self-taught and she being the singleperson crew for the film (apart from some help from her cousin as an assistant and the young actors of the film) probably helped her not only to experiment but also to follow her vision and pursue it to the end.

In the Indian context Rima is indeed an exception and can even be termed as marginal. She spent quite a number of years in Mumbai hoping to become an actress but that never happened. Coming from the hinterlands of a state which is itself marginalised in Indian politics and have no worthwhile cinematic culture to bank upon, Rima’s chances in Mumbai were realistically bleak.

She is never fluent in Hindi and her demure looks are not the ones that Bollywood follows as convention. Coming up with Village Rockstars from that perspective is invigorating and challenging at the same time. The milk of emotion, both human and nature’s, in the film is so genuine and raw that it touches the vulnerable strands within. This ingenuity is so affecting that one will feel the difference from Manas Mukul Pal’s Sahaj Pather Gappo(2017) – the variance is in the auteurs’ personal and first-hand experiences.

While Pal’s film is arresting in parts and is indeed one of the better Bengali films in recent years, yet his middle-class, urban ethos come through in his art. For Rima, in spite of living in big cities significantly she could tap the innocent beauty of her village where she stayed as a kid and returned during the making of this film. If Rima Das and her second feature film in discussion mark the triumph of the outsider in the mainstream in ways more than one another woman director along with the subject of her second feature is also in a way veering on the fringes.

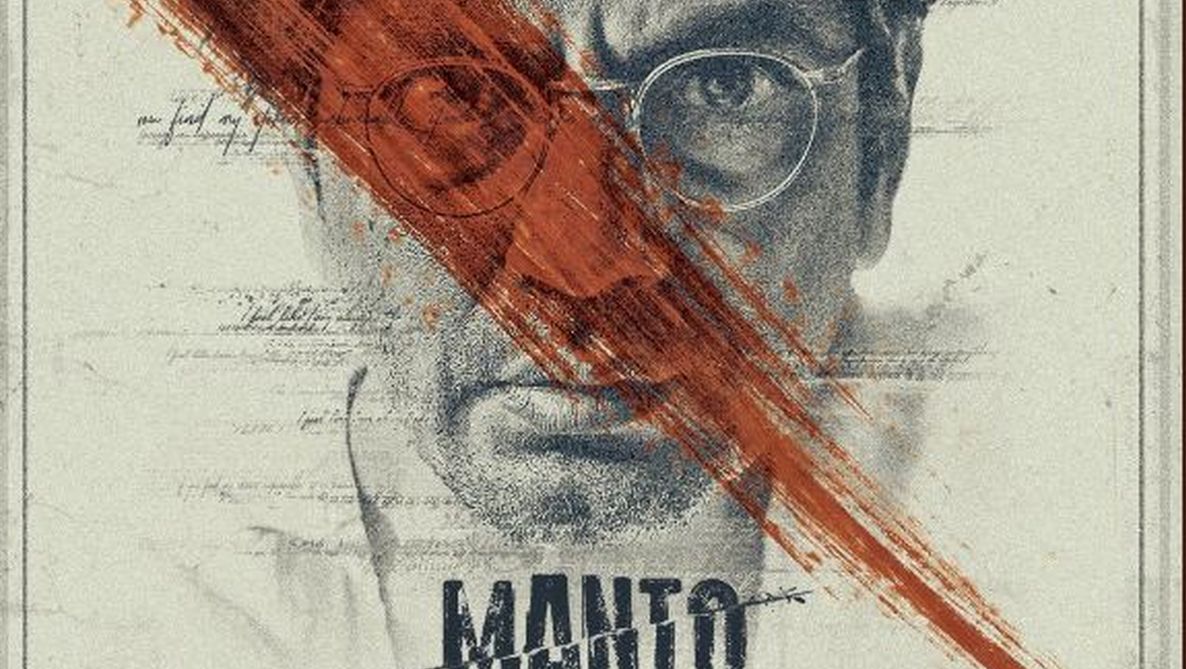

Nandita Das is an actress par excellence, an activist, a social worker and yet she chose to remain on the edges of mainstream Bollywood. In selecting Saadat Hasan Mantoas the subject of her second film Manto she essentially put forth an enigma who was always at the brink of life. Nandita narrowed down Manto’s life to a few years for her film – the ones immediately before the Partition of India in 1947 and shortly after that when he moved to Pakistan.

Nandita mixed Manto’s life with the characters of his short stories juxtaposing them with care and sensitiveness. Yet, there is a feeling of depression for the writer who fought against a regressive society for his art more than anything else and who slowly but surely succumbed to alcoholism out of frustration which dumped him eventually.

Incidentally, three years back in Pakistan Sharmad Khoosat acted as and directed Manto(2015) that was eventually extended as a television series Main Manto. Khoosat’s film didn’t dwell much on Manto’s Bombay life and emotional pull due to Partition and the deep wound that created in his heart and mind. It based significant part of the reel time to Manto’s withdrawal to a mental asylum and his closeness to melody queen Noor Jehan.

These two distinct portrayals of Manto keeping the basic pivot on his agitated soul but trying to find different routes to reach it makes Manto, the most controversial story writer of the sub-continent, even more complex and complicated. It has to be borne in mind that the power of the audio-visual rests largely in the fact that we as audience tend to buy the historicity that is sold to us in biopics. That is why the trigger that initiated Manto’s shift to Lahore after Partition remains shrouded in confusion.

Was it the altercation with his actor friend Shyam Chadda that prompted his exile, as hinted in the film? It will haunt the audience as to why so many Muslims working in the Bombay film industry could stay back in India but Manto had to leave? As a conjecture, probably that dichotomy of fate and in his character is what in essence sums up Manto, the rebel who chose his epitaph -”Here lies buried Saadat Hasan Manto in whose bosom are enshrined all the secrets and art of short story writing.

Buried under mounds of earth, even now he is contemplating whether he is a greater short story writer or God.” Nandita’s film ends with just the hint of Manto landing up in a mental asylum where he wrote his last story ‘Toba Tek Singh’ that was published in 1955 after his death. Set in a mental asylum where the lunatic men were being exchanged as part of a scheme between the governments of India and Pakistan after Partition, the story holds the two nations on a bigger canvas of madness.

As Bishan Singh, a lunatic and main character of the story falls in a ‘no-man’s land’ between the two countries since he is unable to decide which country has his hometown, Manto cries to his own battered soul that is cut into halves during the farce in the name of independence. Nandita Das’s Manto has have been critically acclaimed since its release though there is no surprise in that. Manto as a person is like the conscience of a nation, his denunciation of the society he lived in is one of the most powerful indictments of the system that must make every educated and intellectual Indian feel ashamed.

This is because with all our theoretical intellectualizations we, the urban elite, constantly expect our battles to be fought out by others on our behalf. Saadat Hasan Manto is that medium of our self-ablution, that phantom of self-pity for a life which we don’t wish to have but would love to sympathise. In the film, Manto tells multiple times that he just holds the mirror and reflects the society at large because the dirt is in essence embedded in it. This goes well with our hypocritical moral standards and hence there is no doubt that more than his nerve-chilling stories, the idea of a fallen hero who is an anathema to the society, an anti-establishment rebel for our drawing room debates is what drives home. But that is not essentially Nandita Das’s fault.

It is our urban film-viewing experience and a collective, social amnesia to accept and perpetuate the darkness of life outside us so that our lives and homes remain lighted, in glory. This is precisely why our media gorges us with negative news, horrific depressing accounts and maddening sick stories twenty four hours a day, for seven days in a week. In the process we have tended to dispel the amazing fortitude of our own people.

We have disremembered that along with bleakness and devastation there is an amazing spirit of rural India, that for every Manto we also have a Dhunu and her dreams of becoming a rockstar. That, besides the stories about films churning hundreds of crores with several roles with interchangeable responsibilities, there is also an Assamese film made and managed by only one individual that can also act as a mirror. It is us – the urban, intellectual, know-all Indians who are less enthused to look into it.

Advertisement