BJP MLA Accuses Munde Of Rs 300-Crore Agri Scam And Transfer For Cash Racket

BJP MLA Suresh Dhas also produced a "bribe rate card" which Munde had allegedly charged to give favourable transfers to officials in the Maharashtra Agriculture ministry.

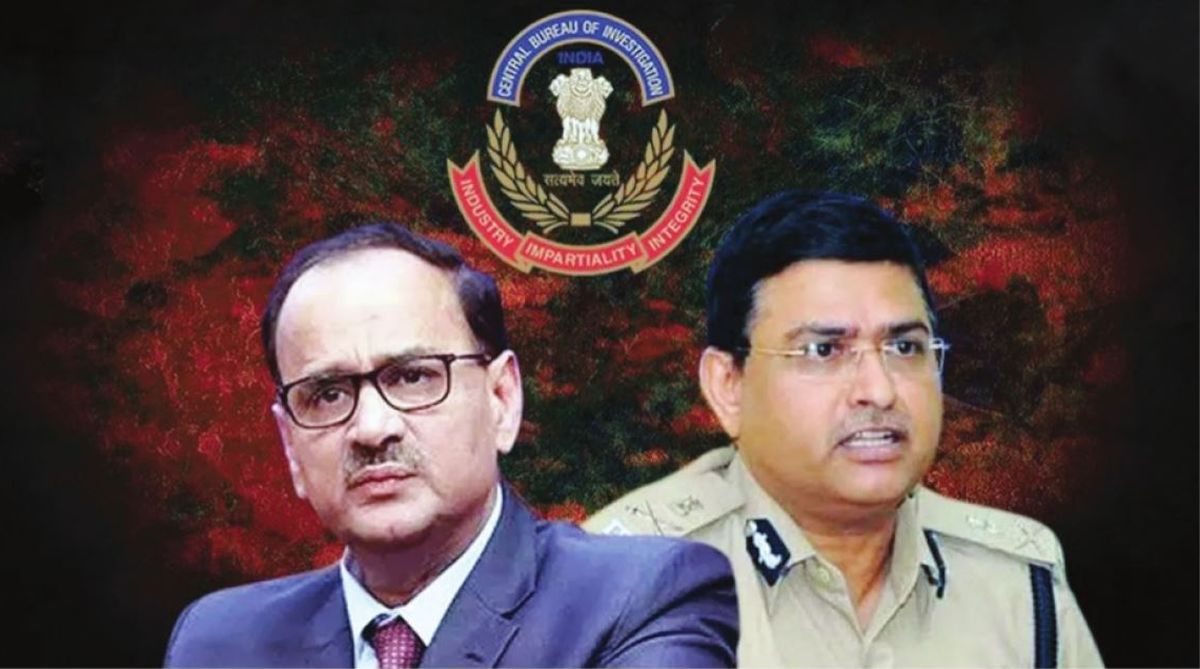

There is a need for drastic overhaul of the manner in which the Central Bureau of Investigation operates, says Ashok Kapur.

The unimaginable has happened. The Centre’s premier investigation agency, the outfit that was reputed to be “incorruptible” and absolutely above board has virtually collapsed, exposing the deep rot within. So many skeletons have tumbled out of its ivory closet that it is now competing with the state police forces which are, by and large already notorious for endemic corruption and gross abuse of authority.

The most embarrassing aspect of the entire drama is that the fall from grace has been so steep and sordid that it may take years to nurse it back to health and credibility. Meanwhile, investigation into important cases, including those having international ramifications and involving serious fraud will have to be either entrusted to state police or to some other Central agency. Either way, it is a fearsome thought. It will impact the entire criminal justice in the country, as will be argued presently.

Advertisement

A recent World Bank study has reconfirmed the obvious, that nations are governed by institutions, howsoever weak and not by individuals, howsoever bright. In the criminal justice system, investigation is the key to eventual success, or failure of prosecution. Undoubtedly, there are other actors also that are part of the chain in the justice system – lawyers, independent courts of law, competent and fair prosecutors etc. But fair and objective investigation is the keystone of the edifice of criminal justice.

Advertisement

In a functioning democracy, institutions cannot be allowed to die. The CBI is virtually dying, long live the CBI. But the resurrection must be thorough and radical, howsoever long and painful. Otherwise, cosmetic surgery will only cover the inner contradictions, and it will be business as usual. A new Director will be posted, a police officer of “unimpeachable integrity” who will be “expected” to resist all “political interference”. Brave words indeed, the nation has heard them ad nauseam. But this time, it has to be a new structure, a result of fresh and innovative thinking.

To enumerate its present form and structure, the CBI is exclusively a police agency, manned exclusively by policemen in mufti. In the overall architecture of Government, it is a specialised directorate which is supposed to report to the controlling ministry, i.e. the Department of Personnel. The latter is manned by civil servants who are, it needs reminding, all trained and experienced magistrates.

The Director of the CBI is the senior-most IPS officer who heads the ‘force’. Under him are several senior officers, all IPS who are junior to him and supervised by him. For all practical purposes, it is a ‘force’ that functions like a uniformed service with strict hierarchical control. Since it is ‘armed’ with wide powers of a police force, including arrest and prosecution, the need for strict discipline can hardly be overstated. It has all the attributes of a police force minus the uniform.

The cause of the present implosion is a raging blood feud between the top two IPS functionaries. Earlier, all the dirty linen was being bleached inside. Reportedly, there were serious allegations of bribery and corruption against its Special Director, number two senior officer. In accordance with the law of the land, an FIR was registered against him by his own organisation, i.e. the CBI. An irony of ironies, the hunter has become the hunted. In what appears to be retaliatory fire, the number two made counter allegations against his superior officer, the Director who is the head of the organization. The former related his tale of woes directly to the Cabinet Secretary.

Meanwhile, as allegations and counter-allegations started flying thick and fast, back and forth, the Government, in a midnight swoop summarily removed both the Director and the Special Director from the scene. It was a very unwise move. The accused and the complainant were put at par, in other words. The Special Director has accused his superior officer, the Director of, inter alia, “interfering” in his work. This is, in the context of working of modern organizations extraordinary conduct – subordinates judging their superiors. It is sure to damage the CBI maybe even permanently.

Such misconduct on the part of a subordinate is all the more serious in an organisation that works on strict hierarchies. There is another questionable conduct on the part of the Special Director. He has written directly to the Cabinet Secretary, which is against the rules. The controlling department is the Department of Personnel which monitors the day-to-day working of the CBI. The Personnel Secretary is the appropriate authority to judge the conduct of the officers serving in the CBI, not the Cabinet Secretary. In another unwise move, the Government has dragged in the NSA, who is an extra-Constitutional authority in the case.

Assuming that there were serious allegations against the Director, a subordinate has no administrative authority to pass judgment against his superiors. Based on this misconduct alone, the Special Director should have been given the marching orders. By treating the two at par, an unhealthy precedent has been set. It can only breed insubordination and worse. The Special Director should have recorded his views on the file, and if the superior officer still overruled him, carry out his written orders without delay or demur. Or, seek a transfer.

After the removal of the two, an interim Director has been appointed. His very first summary order was to transfer a junior officer into exile – Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Admittedly, a superior officer has the right to transfer a junior but he should not have abruptly ordered what appears to be a punitive transfer. Secondly, transfers in the Government generally take place towards the end of the academic season, so that the children’s schooling is not disrupted. There does not appear to be any specific charge against the junior.

Another junior officer has been repatriated prematurely to his parent organization. It is widely reported in the national media that the only ‘charge’ against these officers was that they were investigating serious allegations against the Special Director at the ‘behest’ of the Director. If this be so, it is no charge at all. They were merely carrying out orders of the head of the organisation. To victimize junior officers through arbitrary or punitive transfers is to destroy the morale of the organisation.

The rot in the CBI is much deeper. Another FIR has been filed, this time against a deputy legal head of the agency for forging her record of service. Apparently, legal experts are now part of the CBI who not only prosecute cases in the courts of law on behalf of the agency but tender expert advice on the completion of the criminal investigation. In other words, CBI now has in-house law experts as a part of the prosecution, presumably under the Director.

Such an organisational structure is inherently flawed, in terms of the letter and spirit of the basic law in India. The CBI investigate cases under the Criminal Code (1860) of the nation, the oldest statute in the book. It is an all- India law that was adopted verbatim by independent India after the Constitution was promulgated, both by the Centre and the states, even though ‘police’ is a State subject under the Constitution. It is, arguably, the finest Criminal Code in the democratic world today.

Under the Code, a ‘Prosecuter’, somewhat of a misnomer is generally a senior Government lawyer who is not a part of the prosecution authority but independent of it. This is a wise arrangement to ensure that a prosecution agency gets independent advice on the findings of its own investigation. Should there be any deficient or doctored investigation, the case is not pursued in a court of law, innocent public servants are not harassed and it is nipped in the bud, so to say.

Any number of cases filed by the CBI have resulted in the honourable discharge of the “accused”, which may happen after several years. Meanwhile, reputations are destroyed and the precious time of courts of law wasted. As it is, Court dockets are overflowing. And the most tragic aspect of such a manner of functioning is that police officers who investigate and pursue these cases are seldom if ever held accountable. Scarce manpower is wasted in pursuing these false or frivolous cases. In the same breath, there is a constant chant for more and more staff – the agency is forever complaining of “shortage of staff”.

It is shocking that the Law ministry allowed the scheme of in-house legal counsel which is against the letter and spirit of the Criminal Code. As stated, it is a basic tenet of modern criminal jurisprudence that a Public Prosecutor is somewhat of a misnomer. He is not a part of the prosecution but an “officer of the court” whose task is to assist the court in finding out the truth, not to somehow secure a conviction. A prosecutor as an integral part of the prosecution agency will have little or no credibility in an independent court of law.

Such a sorry state of affairs as exists today in the CBI is symptomatic of lack of any supervision or oversight of the police agency by the Government. It is often reported in the national media that the CBI has filed a charge-sheet in a court of law running into several hundred pages! Such marathon charge-sheets have an implanted device of securing a predetermined result – ‘advantage accused’. No one, least of all a court of law has the time to read such lengthy dissertations.

A highly disturbing fallout from a near-total absence of any oversight, is that somewhere down the line, the agency, in an extraordinary act of conferring a self-serving accolade, has branded itself as the nation’s foremost “anti-corruption” agency. It is indeed a premium brand, it now emerges! A police agency declares itself as the vanguard of anti-corruption crusade in the country, maybe even the sole agency. Evidently, it has conveniently bypassed a recent Transparency International report which has conferred the distinction on police as the most corrupt Government department in India.

In reaching this momentous finding, the international anti-corruption watchdog interviewed the general public, to make a relative assessment of various public institutions in India. Several thousand respondents, almost unanimously rated the police as the most corrupt. If such a purely police entity were to brand itself in such a manner, it can only facilitate the gradual slide of a functioning civilian democracy into an “efficient” police state!

A sideshow in the recent exposé is the bitter infighting amongst senior CBI officers on deputation from same State cadre. As happens in uni-functional services such as police, they serve in the same department throughout their career – there are bound to be personality clashes and differences. When officers from the same State together serve in the CBI, apparently they carry with them some unsavoury baggage from the states. The spillover from the same had so vitiated the working environment in the CBI that a side war was on, as the nation now learns.

Lenin had famously raised the question, after bringing about the overthrow of the corrupt Czarist government: ‘Now what is to be done?’. We must ask ourselves a similar question. A complete overhaul of the CBI must be done, not merely cosmetic changes. It is an investigation agency manned exclusively by police – it should not be headed by a police officer. It should be headed by an IAS officer. It needs to be reiterated that all IAS officers are trained and experienced civil magistrates.

There are several advantages in this innovation. First and foremost, it enshrines a fundamental democratic norm that armed services of the state must be accountable to the civilian executive, a basic certitude of democracy. The police accountability will be in-built. Secondly, he will come with a fresh mind and a fresh approach, unencumbered by any baggage from the police department which police officers bring from their states. The IAS is a multifunctional service with a much wider exposure and the broader vision of a magistrate. He has greater merit: ‘One does not succeed in the IPS, one fails in the IAS.’

Thirdly, there would be an in-built check on the excesses being committed by the CBI police – witness the recent suicide by the entire family of a deputy director general rank officer of the GOI at the hands of named senior officers of the CBI. In the ongoing crisis, it is now reported that a DySP rank officer had summoned a witness several dozen times to ask the same set of questions.

Fourthly, there will be an inbuilt check on such brazen violation of law – charge-sheets running into hundreds of pages. Half a century ago, the Supreme Court had laid down that a criminal charge must be “as concise and as precise as possible”.

The situation is indeed dire. In the memorable words of the Hon’ble Chief Justice of India: “We are shocked at nothing”.

The writer is a retired IAS officer.

Advertisement