Writing for the United States Supreme Court in 1938, Justice Harlan Stone asserted that “prejudice against discrete and insular minorities” may call for a “more searching judicial inquiry” when it tends to “curtail the operation of those political processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minorities”.

These observations were only contained in a footnote of the Carolene Products case but it gained so much traction that it is now widely recognised as the most famous footnote in American constitutional law.

Advertisement

The idea developed in ‘footnote four’ of the ‘Carolene Products’ case can be traced back to basic political and constitutional theory. To protect minorities from the excesses of the majority, rights embodied in the constitution are entrenched and put beyond the pale of bare majorities.

An unelected judiciary is then handed over the power to police those boundaries with the hope that its independence both from the people and from the government will insulate it from popular sentiment and will ensure that decisions are made strictly based on the text of the law and not on the desire and preferences of the people. The judiciary is therefore intended to serve as a counter-majoritarian device that protects minorities.

There is a big problem when the very institution that is supposed to protect these minorities turns its back on them. That is precisely what has happened in ‘Maulana Allah Wasaya vs. Federation of Pakistan’ decided by Justice Shaukat Siddiqui of the Islamabad High Court, a decision which is unparalleled for the astonishing level of invidiousness it contains against a particular minority.

To take just one example, the judgement blames the Ahmadis for “corruption of Pakistan’s democracy” and for creating “regional imbalances” that resulted in the loss of East Pakistan.

The text and tone of the decision could have been more moderate and impartial if the court had tried to solicit representation from the group that it was about to condemn.

Three religious scholars — all Muslims per Article 260 of the Constitution — were appointed as amici curiae. No one from the minority group was invited or appointed to provide an alternate viewpoint.

No wonder the court concluded that citizens should not be able hide their “real identity and recognition” because masking one’s belief was (somehow) found to be inimical to the state’s interests. This conclusion might have turned out a bit differently if the court had given the other party an opportunity of hearing.

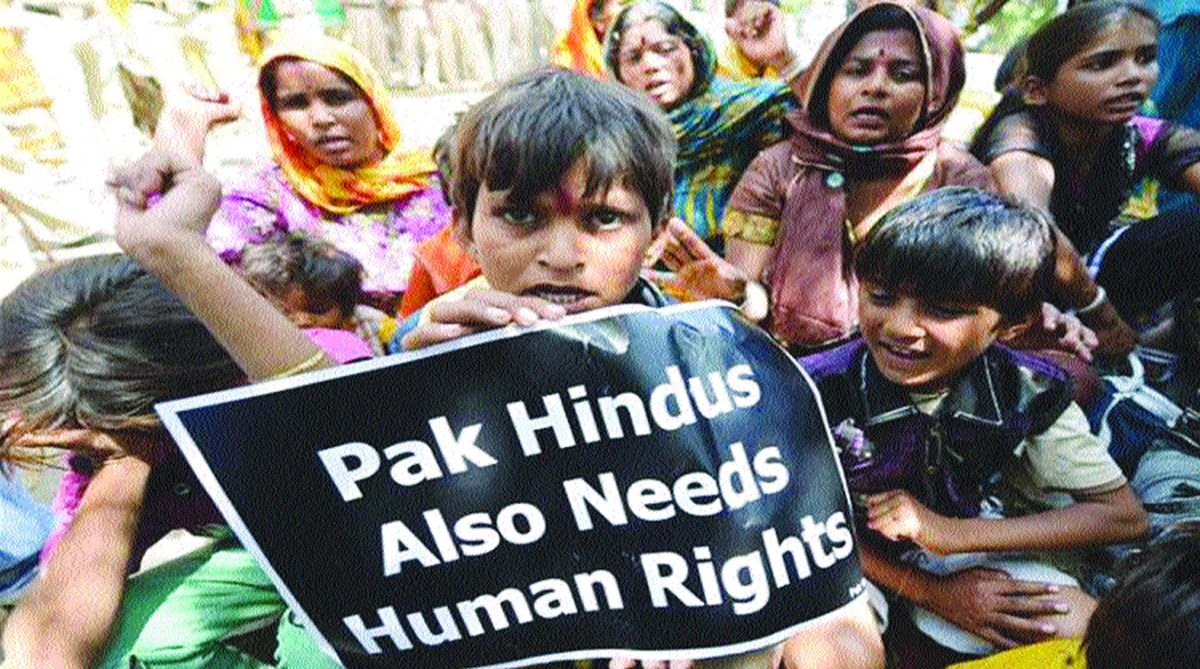

The court, for instance, fails to acknowledge how past state practices may have pushed Pakistan’s minorities to the point where they can no longer live openly and freely without having to suppress their true beliefs, where the freedom to profess and practise their own religion rings hollow, and where their places of worship are unsafe, insecure and at the mercy of the majority.

In a country where the state and its law-enforcement agencies stand as silent bystanders while the places of worship of our minorities are pillaged and ransacked, the only means of escaping this insecurity is to assimilate with the majority; to become less salient in society.

In addition to the court’s failure to appreciate these nuances, the court fails to support its decision with the law of the land. It holds that “Qadianis should either be stopped from using name of ordinary Muslims or in the alternative Qadiani Ghulam-e-Mirza or Mirzai must form a part of their names” but provides no authority that allows the state to tell citizens what names they can and cannot keep.

For how could it? The law does not permit state intrusion in matters involving such deeply personal choices. It is an affront to the dignity of man which is protected by Article 14 of the Constitution. Every citizen has the right to determine what name he wants to be identified with; the state has no business substituting its own choice for his.

Another troubling conclusion that the court arrives at is that every citizen has the right to know what religion people holding key government posts belong to. On this basis, the court directs the government to obtain a declaration of faith before making any such appointment and make that record public.

The court’s animus towards a particular minority is evident from this decision as the state has no reason to inquire into the religious beliefs of those serve it. An attempt to thrust salience upon any minority by judicial fiat must fail.

In these circumstances, the caretaker law minister’s decision to challenge the judgement before the Supreme Court must be welcomed. It offers the highest court of the land a historic opportunity to accept past wrongs and lay down the protections our minorities must enjoy under the Constitution. Who knows, perhaps, this could be our ‘footnote four’ moment?

The writer is a lawyer.