“Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.” These famous words of John F. Kennedy were reiterated by President Obama while endorsing the Iran Nuclear deal formally known as Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

In 2015, Iran and the P5+1 (United States, China, France, Russia, and UK, plus Germany), along with the EU, reached an understanding on a Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) to address concerns over Iran’s nuclear programme.

Advertisement

It was the culmination of political and diplomatic efforts to find a negotiated solution to curb Iran’s alleged efforts to develop a nuclear weapon and guaranteeing that the programme is exclusively for peaceful purposes.

It is a comprehensive, long-term deal with Iran that will prevent it from obtaining a nuclear weapon. The JCPOA was the culmination of several months of hectic negotiations between the parties. This JCPOA was endorsed by Security Council Resolution 2231.

This Resolution comprised more than 100 pages of text which included the entire JCPOA text as an annexure. The Security Council Resolution observes its commitment to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and the need for all States party to that Treaty to comply fully with their obligations.

The full implementation of JCPOA would ensure the exclusively peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear programme. Iran also reaffirmed under JCPOA that under no circumstances would it ever seek, develop or acquire any nuclear weapons. As per the terms of JCPOA Iran had many obligations including modifying the core of its Arak reactor so as to disable it from the capability of producing weapons-grade plutonium.

Iran had agreed to ship the spent fuel from the reactor out of the country for the lifetime of the reactor and it is further forbidden from building new heavy-water reactors. Constant international supervision has been made mandatory including supervision of its centrifuges. Iran has been further prohibited from using its advanced centrifuges to produce enriched uranium for another 10 years. Iran has to destroy most of its stockpile of enriched uranium.

The European Union and European Union Member States also terminated provisions of Council Regulation (EU) No 267/2012 implementing all nuclear-related sanctions or restrictive measures, terminated provisions of Council Decision 2010/413/CFSP.

The United States under the JCPOA committed to cease the application of, and to seek such legislative action as may be appropriate to terminate, or modify to effectuate the termination of, all nuclear-related sanctions and further to terminate Executive Orders 13574, 13590, 13622 and 13645, and certain sections of Executive Order 13628.

The UN Security Council resolution terminated all provisions of previous UN Security Council resolutions on the Iranian nuclear issue i.e. 1696 (2006), 1737 (2006), 1747 (2007), 1803 (2008), 1835 (2008), 1929 (2010) and 2224 (2015).

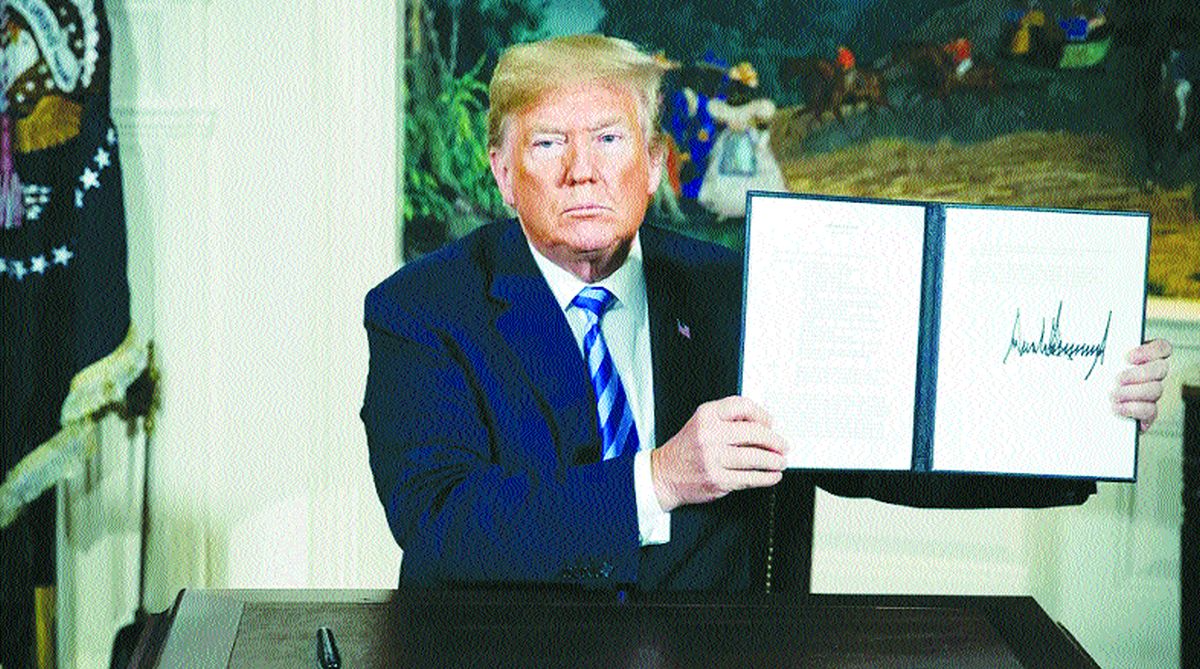

Now the United States has unilaterally withdrawn from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and has further declared that it is set to impose the ‘strongest sanctions in history’ against Iran. Other parties to the JCPOA have condemned the US action.

The Joint statement by High Representative Federica Mogherini and Foreign Ministers of E3 (France, Germany, United Kingdom) on the re-imposition of US sanctions due to its withdrawal from JCPOA observes that JCPOA was working and delivering on its goal i.e. ensuring that the Iranian programme remains exclusively peaceful, as confirmed by the IAEA in subsequent reports.

JCPOA has been a key element of the global nuclear non-proliferation architecture, crucial for the security of Europe, the region, and the entire world. The Joint statement supporting the lifting of nuclear-related sanctions states that it was an essential part of the deal which boosted not only trade and economic relations with Iran but also improved the lives of the ordinary Iranian people.

It declared that it was determined to protect European economic operators engaged in legitimate business with Iran, in accordance with EU law and with UN Security Council resolution 2231 and it thus brought into force the European Union’s updated Blocking Statute to protect EU companies doing legitimate business with Iran from the impact of US extra-territorial sanctions.

As the JCPOA was made a part of the UN Security Council resolution 2231, questions are being raised on the legality of the unilateral withdrawal of the United States. The United States maintains that it is not legally binding. The US contends that there are various multilateral initiatives which are not legally binding.

Few examples of such initiatives include Proliferation Security Initiative which is an effort involving more than 100 countries aimed at stopping the trafficking of weapons of mass destruction.

Vienna Declaration on nuclear safety is also an initiative to prevent nuclear accidents and mitigate their radiological consequences. Missile Technology Control Regime is also an association of various countries to coordinate export licensing efforts to prevent the proliferation of unmanned delivery systems capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction.

Hague Code of Conduct Against Ballistic Missile Proliferation is another multilateral arrangement involving many countries to curb ballistic missile proliferation worldwide. The U.S.-Russia framework to remove chemical weapons from Syria (2013) similarly outlines the steps for eliminating Syria’s chemical weapons.

There has been controversy regarding the binding nature of the Security Council Resolutions. The International Court of Justice in the Case Concerning Questions of Interpretation and Application of the 1971 Montreal Convention arising from the Aerial Incident at Lockerbie (Libya v. United Kingdom) (1998) has observed that not all Security Council resolutions can have legal effect as a Security Council resolution which was adopted before the filing of the Application could not form a legal impediment to the admissibility of the application as the World Court held it to be a mere recommendation without any binding effect.

Article 25 of the UN Charter states that the Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the Charter. Speaking on the interpretation of the Article, the World Court has observed that when the Security Council adopts a decision under Article 25 in accordance with the Charter, it is for member States to comply with that decision, including those members of the Security Council which voted against it and those Members of the United Nations who are not members of the Council.

The World Court in its Advisory Opinion in the Legal Consequences for States of the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970) has categorically rejected the contention that Article 25 of the Charter applies only to enforcement measures adopted under Chapter VII of the Charter.

It observed that Article 25 is not confined to decisions in regard to enforcement action but also applied to the decisions of the Security Council adopted in accordance with the Charter reasoning that the Article 25 is placed in that part of the Charter which deals with the functions and powers of the Security Council and not in Chapter VII.

It further observed that the language of a resolution of the Security Council should be carefully analysed before a conclusion could be made as to its binding effect. Providing a guiding principle, it observed that in view of the nature of the powers under Article 25, the question whether they have been in fact exercised is to be determined in each case having regard to the terms of the resolution to be interpreted, the discussions leading to it, the Charter provisions invoked and, in general, all circumstances that might assist in determining the legal consequences of the resolution of the Security Council. It has to be analysed whether the Security Council resolutions are couched in exhortatory rather than mandatory language.

As the text of the preamble of resolution 269 (1969) mentioned that the Security Council was mindful of its responsibility to take necessary action to secure strict compliance with the obligations entered into by States Members of the United Nations under the provisions of Article 25 of the Charter of the United Nations, the Court reached the conclusion that certain decisions made by the Security Council were consequently binding on all States Members of the United Nations, which were under obligation to accept and carry them out.

Not with standing Security Council resolution 276 (1970), on the legal consequences arising for States from the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia the Court observed that a binding determination made by a competent organ of the United Nations to the effect that a situation is illegal cannot remain without consequence.

Once the Court is faced with such a situation, it would be failing in the discharge of its judicial functions if it did not declare that there is an obligation, especially upon Members of the United Nations, to bring that situation to an end. The decision thus entailed a legal consequence, namely that of putting an end to an illegal situation.

Generally, the question whether an agreement results in a binding commitment under international law or not is not easy to answer and there remains ambiguity in the tests formulated for determining this. The Obama Administration treated the plan of action as a nonbinding political commitment for which congressional or senatorial consent was not required. Under the domestic law of the United States, President Trump can withdraw from the JCPOA. But some international law experts argue that the U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231 had converted certain provisions in the JCPOA into obligations that are binding under international law.

The US Congress instead of directly approving the JCPOA, passed the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act which authorises the President to certify every 90 days that Iran is transparently, verifiably, and fully implementing the agreement, including all related technical or additional agreements; it has not committed a material breach with respect to the agreement or, if it has committed a material breach, has cured the material breach; it has not taken any action that could significantly advance its nuclear weapons programme; and the suspension of sanctions related to Iran pursuant to the agreement is appropriate and proportionate to the specific and verifiable measures taken by Iran with respect to terminating its illicit nuclear program and vital to the national security interests of the United States. If the president withholds the certification or reports that Iran has committed a breach, then Congress can introduce legislation re-imposing the nuclear sanctions.

The President possesses authority to terminate the United States’ participation in the JCPOA and further to re-impose the sanctions on Iran by declining to renew waivers or through executive order. But there is no clear answer whether such action is fully compatible with the International Law regime considering the inclusion of the JCPOA in the Security Council resolution 2231.

Now in Alleged violations of the 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights (Islamic Republic of Iran v. United States of America), Iran has instituted proceedings against the United States before the ICJ with regard to the dispute concerning this decision of the United States to re-impose in full effect and enforce sanctions and restrictive measures which the United States had previously decided to lift in connection with the JCPOA, alleging breach of multiple provisions the Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights between Iran and the United States. A World Court’s determination on this issue could bring more clarity to this complex and fragile situation.

The writers are Mumbai-based advocates and legal consultants.