Nicole Kidman opens up on teaming with 19 female directors since 2017

Kidman surpasses her #MeToo-era pledge, working with female directors 19 times since 2017 to support women in Hollywood.

The conviction of Bill Cosby shows that denouements are possible in cases of sexual misconduct by powerful persons, say Joyeeta Banerjee and Rajdeep Banerjee.

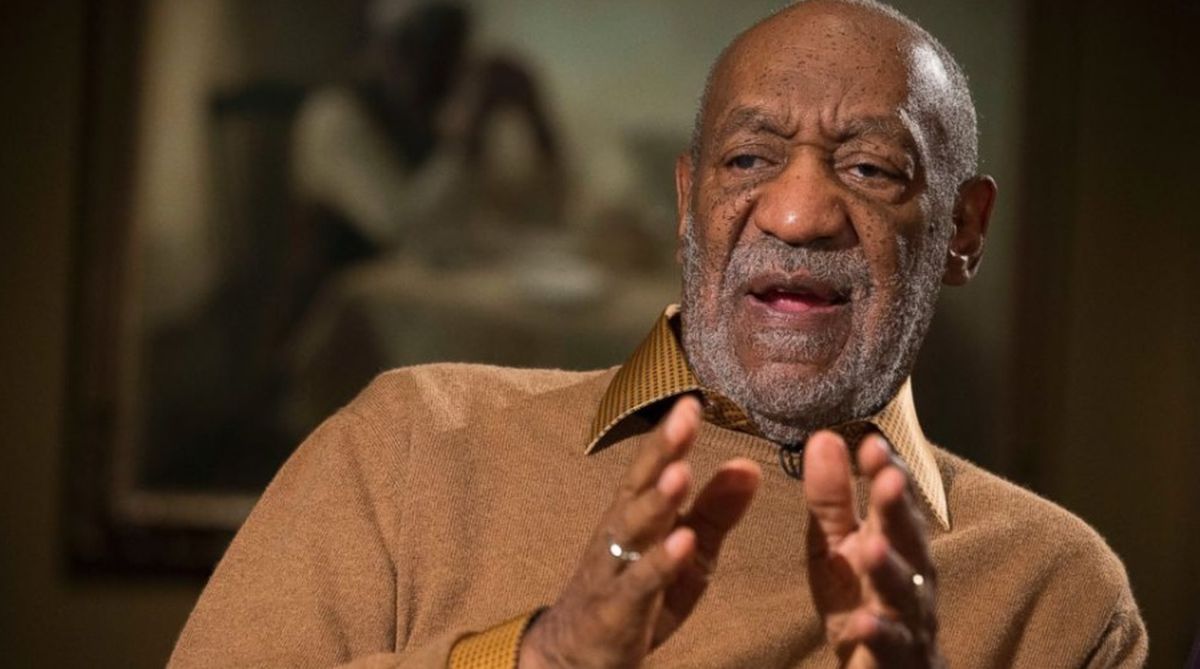

Bill Cosby (PHOTO: Facebook)

‘I won’t go away, there is a lot more I will say.” This tweet from Andrea Constand in 2014 has finally culminated in the criminal prosecution against Bill Cosby and his conviction. But punishing the powerful entertainer for his wrongdoings was not at all easy.

Cosby too filed many cases before various courts to prevent his sexual crimes from being punished. A large number of women – more than 60 – have come forward and accused Cosby of sexual assault with the earliest assault allegations taking place in the 1960s.

Advertisement

Most of the alleged crimes have passed the limitation period for criminal prosecution. Cosby’s first criminal trial, on three counts of indecent assault of Andrea Constand ended in a mistrial due to a hung jury in June 2017. But in the retrial which was post the #MeToo movement, Cosby has been convicted and sentenced. During this retrial five additional victims recounted similar abuses.

Advertisement

In fact, Constand had in 2005 sued Cosby saying that he drugged and sexually assaulted her at his Montgomery County home. During the discovery process, Cosby was questioned regarding his relationships with other women. The Court had then passed an interim order in November 2005, wherein it required the parties to file under seal their discovery motions and any supporting documents. But the Court denied a permanent seal.

The parties later settled the case in 2006 as per a Confidential Settlement Agreement. As per the terms of the agreement the parties were not to disclose to anyone, via written or oral communication or by disclosing a document, in private or public, any aspect of the litigation, including the events or allegations upon which the litigation was based as well as the information that they learned during the criminal investigation of Cosby or discovery in the content of Cosby’s and Constand’s depositions in the litigation, and information about Cosby and/or Constand gathered by their agents.

After Cosby and Constand reached a confidential settlement in late 2006 the case was dismissed. Thus, the Court could not rule on whether the documents could remain sealed permanently and hence the interim sealing order continued. In such circumstances the District Court’s Rules required that the Clerk of Court to send a notice to the attorney for the party who submitted the sealed documents stating that the documents would be unsealed unless an objection was filed but eight years passed without any such notice being sent.

Then in December 2014, Associated Press requested that such a notice be issued. A notice was put on the District Court docket stating that the documents would be unsealed within 60 days unless an objection was filed. Cosby then filed an objection and the question before the Court was whether the court documents which included Cosby’s deposition could be made public. This assumed significance as his deposition included admission of providing drugs and then having sex.

The Court quoted Goldstein v. Forbes (In re Cendant Corp.), 260 F.3d 183(3d Cir.2001) wherein it was observed that it was well-settled that there exist, in both criminal and civil cases, a common law public right of access to judicial proceedings and records as the public’s exercise of its common law access right in civil cases promote public confidence in the judicial system by enhancing testimonial trustworthiness and the quality of justice dispensed by the court.

The Court observed that the party seeking a protective order bear the burden of showing good cause and the courts should consider various factors as suggested in Pansy v. Borough of Stroudsburg, 23 F.3d 772(3d Cir.1994). These include whether disclosure will violate any privacy interests; whether the information is being sought for a legitimate purpose or for an improper purpose; whether disclosure of the information will cause a party embarrassment; whether confidentiality is being sought over information important to public health and safety; whether the sharing of information among litigants will promote fairness and efficiency; whether a party benefitting from the order of confidentiality is a public entity or official; and whether the case involves issues important to the public.

Rejecting Cosby’s argument the Court observed that the documents were not technically sealed at that time as the Court had initially sealed them temporarily in its efforts to resolve the outstanding discovery disputes and also indicated that the seal would lapse if not definitively extended. Commenting on the privacy interest, the Court observed that there is a curtailment of the interest for persons holding public office and though this does not expressly extend to “public figures” who are outside the category of office holders, earlier precedents suggested that the privacy interest may be diminished when a party seeking to use it as a shield is a public person subject to legitimate public scrutiny.

As Cosby had freely entered the public space and thrust himself into the vortex of public issues, he did voluntarily narrow the zone of privacy that he was entitled to claim. Also, Cosby had publicly denied the various allegations made by several women and had further doubted the motives of the victims and thus by joining the debates about the cases, had further diminished his entitlement to a claim of privacy.

Associated Press’s interest in obtaining Cosby’s depositions was held legitimate as the primary purpose for which the deposition was sought was not merely commercial gain or any prurient interest in exposing the details of his personal life. Rejecting the contention that the very nature of the allegations which included drugs and seduction cloaked the case and the depositions with an automatic seal of silence, it observed that such a construction could then create a new category of cases which because of its inflammatory subject matter would always lie outside public scrutiny. Cosby thus had a diminished privacy interest which was outweighed by the Associated Press’s and the public’s interest in gaining access to his testimony.

The Court also rejected Cosby’s suggestion that releasing the deposition testimony could have a chilling effect on other settlement agreements as then parties would not be able to rely on the persistence of confidentiality. The Court pointed that the parties could have ensured the permanency of a seal by simply requesting a court order to that effect.

Countering the argument of Cosby that releasing the deposition could impact jury selection in another case, the Court relying on Shingara v. Skiles, 420 F.3d 301 (3d Cir.2005) observed that ordinarily the district court is able to select a fair and impartial jury in cases even where there has been pre-trial media attention to the case.

It quoted the Third Circuit which had refused to countenance the generalised concern that disclosure would affect a fair and impartial jury where the defendants did not present any evidence to support their argument, drawn from the information already published, that there will be difficulty selecting a jury in the case or evidence that if additional information is published there would be such difficulty.

Thus, the Court after balancing all the pertinent Pansy factors found that Cosby had failed to articulate any specific, cognizable injury that would result upon the documents’ release to the public and thus ordered the documents to be unsealed.

In another action Cosby claimed breach of contract and unjust enrichment against a number of parties to the settlement agreement, including Andrea Constand, alleging that they have violated the agreement. One of the issues before that Court was to the extent that the Confidential Settlement Agreement purported to prevent its signatories from voluntarily disclosing information about crimes to law enforcement authorities. It observed that where the enforcement of private agreements would be violative of public policy, it was the obligation of courts to refrain from such exertions of judicial power.

In Fomby–Denson v.Dep’t of Army, 247 F.3d 1366 (Fed.Cir.2001), the United States Army had hired Ms. Eloise Fomby-Denson but later on because of certain forgery charges, Army terminated her employment. When she challenged the action, Fomby–Denson and the Army entered into a settlement agreement wherein the Army agreed to cancel her termination and to pay her an amount. Terms of the settlement agreement specified that its terms would not be publicised or divulged in any manner, except as is reasonably necessary to administer its terms. The Army then referred the allegations of Fomby-Denson’s forgery to local law enforcement authorities for investigation and possible prosecution and in the process disclosed some of the terms of the settlement agreement with those authorities. When Fomby- Denson attempted to enforce the settlement agreement the Court refused to do so.

The Supreme Court in W.R. Grace Co. v. Local Union 759, 461 U.S. 757 (1983) had observed that the public policy interest at stake in the reporting of possible crimes to the authorities is of the highest order and is indisputably well defined and dominant in the jurisprudence of contract law. The Supreme Court had observed in Roberts v. United States, 445 U.S. 552 (1980) that concealment of crime has been condemned throughout history. The citizen’s duty to raise a `hue and cry’ and report felonies to the authorities was an established tenet of Anglo Saxon law at least as early as the 13th century.

The court took note of few judgments such as Lachman v. Sperry-Sun Well Surveying Co., 457 F.2d 850 (10th Cir. 1972) wherein the defendant informed a third party of the plaintiff’s possible misappropriation of certain oil and natural gas deposits belonging to the third party. The plaintiff sued for breach of a non-disclosure agreement but the courts dismissed the action on the basis that public policy will never penalise one for exposing any wrongdoing.

Again in Berman v. Coakley, 243 Mass. 348 (1923) the Court had observed that a private agreement made in consideration of the suppression of a criminal prosecution will neither be enforced nor abrogated by a court of equity as the doctrine is founded upon the public policy that the course of justice cannot be defeated for the benefit of any individual.

The Court thus observed that as it was a long-standing principle of general contract law that courts will not enforce contracts that purport to bar a party. The Court held that the United States Army could not be stopped from reporting another party’s alleged misconduct to law enforcement authorities for investigation and possible prosecution. The Cosby Court thus held that to the extent the Confidential Settlement Agreement purported to prevent its signatories from voluntarily disclosing information about crimes to law enforcement authorities, it was unenforceable as against public policy.

The multitude of cases and motions by Cosby to stall the trial and conviction but his inability to succeed clearly indicates that sexual-assault victims cannot be simply disbelieved anymore and sexual abuses by powerful men will no more be tolerated in the society and will be punitively dealt with.

The writers are Mumbai-based advocates and legal consultants.

Advertisement