Power transmission, distribution losses in J&K highest in country: CM Omar Abdullah

Chief Minister Omar Abdullah on Wednesday said that at 50 per cent, the transmission and distribution losses in Jammu and…

The reviewer is associate professor of English, Brahmananda Keshab Chandra College, Kolkata and is secretary, Intercultural Poetry and Performance Library, Kolkata.

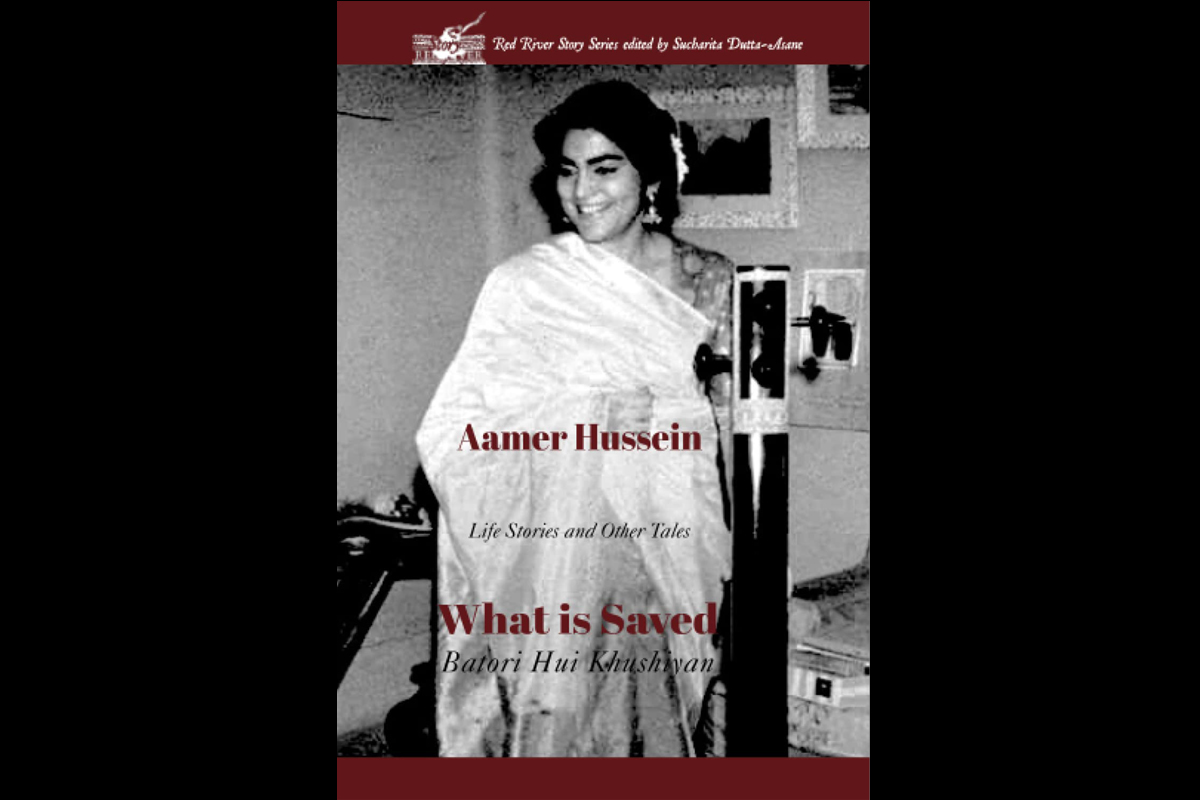

Writers writing about their works, about their life stories, and about things that find ways into their writings have always been interesting. They reveal, at times, aspects of their life and art, of their thoughts that find ways into their writing. Aamer Hussain’s What is Saved is one such work. A British-Pakistani writer, Hussein is well known for his collections of short stories – The Blue Direction, Insomnia, 37 Bridges and Zindagi Se Peble, and two novels – Another Gulmohar Tree and The Cloud Messenger and a collection of essays on Urdu literature – House of Treasures.

What is Saved consists of writings that have been previously published in two other collections: Hermitage and Restless: Instead of an Autobiography. Some of the short stories in the volume have been earlier published as well. Born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan, Hussein spent some years in India as well before he moved to England. The work under review is a collection of stories that weave memoir, fiction, and poetry, revealing Hussein’s literary art and work. In an afterword to the volume, Hussein notes that “writing about fictions risks becoming another fiction . . .” He then, however, goes on to speak of the stories in the volume and how they began, as well as the genre.

Advertisement

Another group of stories about illness and the pandemic move back and forth between memory and imagination, between faithful chronologies and an unfaithful relationship with real time. ‘A Convalescence’ and ‘The Yellow Notebook’ stay very close to life, and yet I categorise the former as a story and the latter as memoir, but the slipper term autofiction perhaps covers them all.

Advertisement

The stories in What is Saved carve a huge historical space, beginning in 1857 and moving on to the present, to the pandemic that has been so much a part of our lives. Literary and historical figures, people from his life, and characters from fiction all come together in them. “Uncle Rafi” speaks of his mother’s maternal uncle, “whose delightful; volume of short stories, Kehkashan, was published only after his early death at the age of 33.” It speaks of Uncle Rafi, whom his mother called Mamu Mian, of his life and work, and of how he would have reacted to the historical change.

Would his liberal attitudes have hardened into dogma, or would he have swung to conservatism in the Pakistan to which his brothers migrated, as he too probably would have? Or would his fiction have echoed the calm voice of conscience?

The stories speak of relationships, of music, of place and time; some lead on to other stories, much in the tradition of storytelling. .” In the third paragraph of “The Yellow Notebook” Hussein writes, “But let me try to begin at the beginning,” a line that then takes us into stories, to memories recreated.

The interior landscapes of the human mind create new ways of looking at life around them. The “Hermitage,” for instance, speaks of how Mridul finds himself in a new place that is in stark contrast to his own life. The verdant space of the hermitage begins to influence him: “But one morning he became aware of a change that had been taking place in the air around him. Written in a conversational style, the piece brings together seemingly disjointed ideas.

All my life, I’d believed the book of life was interleaved, like those bilingual editions that carry different facing pages—happy moments on one side, perhaps on a gilt-edged page, and sorrows on the other, edged in black.

The stories weave in movement across continents and across spaces that linger on and influence life in its various forms. There are bonds and friendships forged at various points in the pandemic that shook us to the core of life as it unfolded. Written in a variety of styles, some conversational, some narrative, and some in the nature of journal entries, the stories also bring in the history of the Indian subcontinent. “The Cusp” is written in the manner of journal entries, and Hussein mentions in the afterword that it is a “lived experience reimagined” and that it belongs to the “realm of fiction.”

“Last January, my year of mourning wasn’t over. I hated lockdown and isolation, the dark, short days, and the deaths. Those writings came from a time of grief and separation. These days I watch the sun rise and the sky change colour, and I wait for February and early pear blossom.”

Red River is an independent publisher that has been publishing poetry in India for some years now and has carved a place for itself when it comes to English poetry in India. This volume is their first venture in their new imprint called Red River Story. Wonderfully edited by Sucharita Dutta-Asane, the stories create colourful tapestries of life and fiction.

Advertisement