KMC focus on slum area development for next fiscal

With emphasis on women-centric projects, the city’s slum areas are slated for an infrastructural development in the next fiscal.

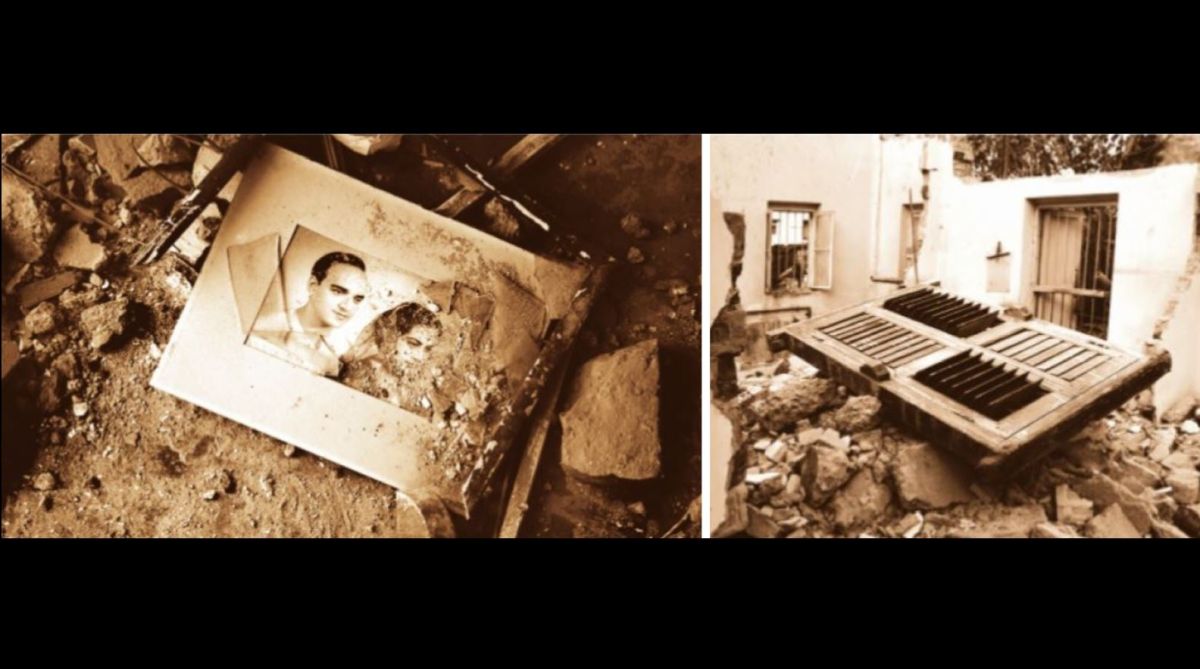

As old buildings are razed to ground overnight, they disappear into rubble and with it a piece of the citys history, culture and way of life too vanishes. In a documentary titled Khawto (The Wound) lensman Bijoy Chowdhury captures the demolition of one nondescript old house to tell a story of a city losing its identity.

Burdened by demographic pressure and the realtor-politician nexus, Kolkata is forced to sacrifice its old buildings. Old houses that gave the city its uniqueness are being pulled down to make way for space-efficient eyesores.

Sometimes rambling and apparently abandoned old houses that gave Kolkata its uniqueness are spotted standing mysteriously against modern-day eyesores, waiting to disappear suddenly one day. We call these new houses eyesores not because they are modern, but because the new high-rises in Kolkata do not match up to the benchmarks of what we see across the world.

Advertisement

Kolkata’s old houses are not just mansions of the social gentry or aristocratic Bengali families whose younger generations left the city for good. They are often a row of houses in a north Kolkata lane or even a south Kolkata neighbourhood.

Advertisement

Kolkata is not about a few humongous British era buildings like Victoria Memorial or Governor’s House. Its’ interesting collage is of the houses built by our forefathers of all economic strata and yes, some gems built by the wealthy social gentry as well. They came up over two centuries. The mélange of small, medium and big houses form the city’s signature neighbourhoods that now face the onslaught of mindless destruction.

The buildings are recognised by their green slatted french windows, curved balconies, wrought iron works, beautifully designed cornices. Many of these houses were painted either yellow or red. But then who cares if Kolkata’s signature canvas fights a losing battle against criminal apathy towards its heritage?

So the question is sometimes, does an old family picture, hanging on one of the damp walls of the centuries-old house become important enough to be carted away to be hung in the swanky apartment of a modern condominium? Old kitchen utensils, bric-a-bracs that come with an attached memory, which were so important in the old house turn into trash in the face of modern gadgets in the luxurious apartment.

Lensman Bijoy Chowdhury, who has been working on various aspects of Calcutta/Kolkata for the past 35 years, captures all that in his documentary Khawto, meaning the ‘wound’ in English.

Chowdhury’s camera has chronicled the process of wrecking the city’s urban legacy but choosing the fate of one such house. Every blow that demolishes the house chunk by chunk razing to dust a part of our social heritage, a viewer would suffer as if the blows are raining on him. But he has not been content in documenting the loss. He has delved into the human side of this destruction. He has captured the forced rejection of memories that were once dear to us.

Old family photographs left damaged on the walls of an abandoned dwelling awaiting demolition, old kitchen utensils, small artefacts of everyday life, left behind because they cannot be taken with the owners to the cramped new highrise flats where modern appliances enjoy a vaulted position.

The heart-wrenching demolition of a house he captured belonged to his own friend who later settled abroad. And he captured more than just demolition of the house.

“My camera followed also those people whose livelihoods have been affected owing to the demotion of the old city,” said Chowdhury.

“These migrant workers have left the faded glories of their own once culturally and architecturally rich towns, such as historic Murshidabad,” he said referring to the workforce that was part of creating those beautiful old houses and mansions.

“The film intends to hold the intuitive knowledge of how to frame them to provide more than a documentary of the changes in the urban fabric and its displaced inhabitants that once gone will never return, and the mysterious beauty of the man-made ruins that mark the transition from the Calcutta of authentic tradition to the so-called new ‘modernity’,” said Chowdhury. The documentary is relevant as more Kolkata buildings are razed to ground.

While the city celebrated Durga Puja this year (2018) and people went overboard over the pandals that are created so meticulously by our artisans, always drawing from our rich architectural heritage across the country, in south Kolkata perhaps the city’s most beautiful house was torn down by the realtors.

The magnificent building that belonged to once famous Sanskrit scholar Gurupada Haldar, considered an authority in Sanskrit studies, was demolished during the Pujas while the court was in vacation. According to an English daily, 60 per cent of the house at Kalighat was demolished as the youngest heir of the family alleges that a developer, to whom other family members illegally sold off their portions, embarked on the demolition although he had won a case at a lower court for keeping the house.

A few social media protests by concerned groups of people are perhaps too insignificant and feeble voices against the army of powerful people waiting to benefit from the rubble of old Kolkata. People visiting Kolkata do not come for watching its goofy wax museum or even an eco-park. They come for a cultural experience. That is what the investment parched city and the state can offer even now.

As old buildings are razed to ground overnight, they disappear into rubble and with them a piece of the city’s history, culture and way of life too vanishes. The wound of demolition history will never heal, as the documentary by Chowdhury captures so starkly.

IBNS

Additional reporting by Sujoy Dhar and Uttara Gangopadhyay.

All Images by Bijoy Chowdhury are part of his documentary.

Advertisement