Solitary confinement is a form of punishment that can make a person feel like “a caged animal” and cause severe psychological problems. John Galsworthy wrote a play in 1910 to graphically bring out the excruciating mental pain, humiliation and helplessness felt by people subjected to such confinement. Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary, and RugglesBrise, head of the Prison Commission, saw the play and were moved. The result was that the period of solitary confinement was reduced to 1 to 3 months.

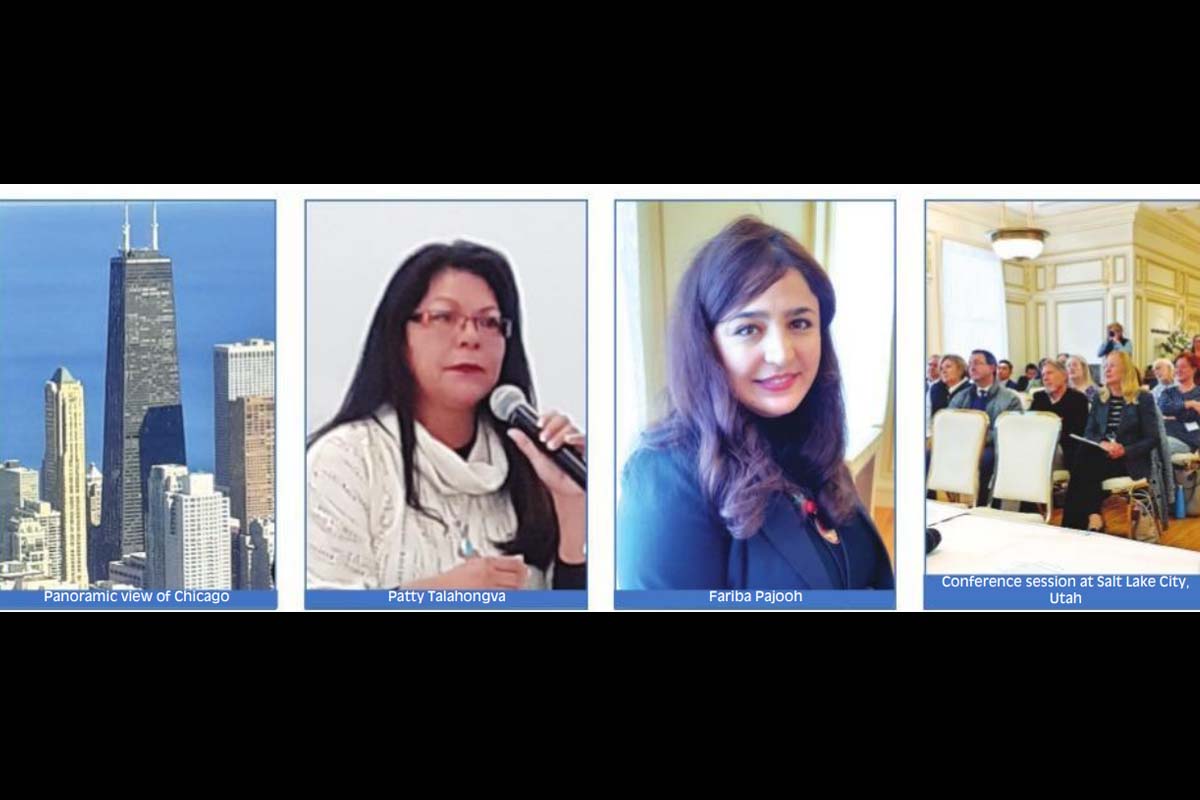

It is still resorted to in our times to crush the feeling of human dignity, selfrespect and the spirit of independence. I met one such victim at Salt Lake City, Utah in the US while participating in a global conference on religious-political conflicts and tackling them. Her name is Fariba Pajooh, a young woman journalist from Iran, who had to go through the infernal agony of solitary confinement in her country. She was charged with collaborating with foreign media to malign the country. But, what she did, according to her, was nothing but presenting facts that she could glean as a conscientious journalist and dispatched her reports to a foreign media she was working for.

Advertisement

The powers that be were, however, not convinced and she was awarded the sentence of solitary confinement in a small, sunless cell. For the first few days she was so traumatised that she only “cried, cried and cried.”

“The whole world was shut out to me. My cell was enveloped in the silence of the grave,” she closed her eyes and travelled in her mind to the cramped cell years after her confinement. The only human contact she had was when the jail guard brought her distasteful meals. That was no solace at all. She lay huddled up in one corner of the cell and was all the time greeted by a deafening, intolerable silence.

“Then one day I heard a sound. I jumped up and strained my ears in utter desperation. First, it was a very faint thud, but then it gradually reached a crescendo of a banging sound. I leapt up in joy. At last there was a sign of some activity, some life. The sound declared the presence of some human being for the first time since I had been thrown into the cell a few days back.

“The only thought that ran across my mind was that at least I am not alone. I had a companion in the form of a dull, inarticulate thud. And I was so grateful! For the rest of the period of my confinement stretching into months this rhythmic banging reassured me I was not alone, I had a companion nearby, somewhere in the same part of the prison I was lodged in,” Fariba reminisced as if she were re-enacting the sordid scenes.

After her release she frantically tried to find out the cause of the sound. She was driven by her journalistic instinct as well as her sense of gratitude to the maker of the sound. She came to know it was none other than a fellow victim of solitary confinement, an American woman social activist held captive. It was she who realised through her own pain how invaluable even a dull sound can be to those suffering like her. So, she tried to send the message across through her mad banging that there was still a sign of life in the horror world of deadly silence in the solitary cells.

As Fariba spoke, her sweet, captivating smile never deserted her face. When I asked her how she could retain such a bubbly spirit, she told me the solitary confinement had taught her the value of cheerfulness in life.

Patty Talahongva is a Hopi journalist, documentary producer, and news executive. She was the first Native American anchor of a national news program in the USA and is involved in Native American youth and community development projects. The daily digital news platform ~ Indian Country Today ~ covers the indigenous world, including American Indians and Alaska Natives.

She is a fluent speaker with a melodious voice and is proud of her indigenous origin ~ Hopi. “I am an Indian, a Red Indian. I am so glad to meet you, a greater Indian,” she told me exuding warmth.

“Yes, Columbus’ mistake has brought you and me within the same Indian brackets, though we live thousands of miles apart. That is the beauty of his error in judging where his ship finally anchored,” I replied and she broke into rippling laughter

While asserting the religious belief of her people, she explained how nature has got integrally linked with their religion. So much so that it has given a new connotation to the fight for the preservation of ecological balance and against global warming.

For the indigenous people whose cause she espouses, climate change is an onslaught on their religion too. The snow-capped region in Alaska they live in is so sacred to them and the raw nature is part of their religious consciousness. When global warming causes the ice to melt, it’s not simply an environmental issue for them, but primarily a profound religious question. Patty gives an entirely new dimension to the global fight against climate change.

The writer is co-ordinating editor, The Statesman, Kolkata.