Cutting Red Tape

Transformative technological innovations of the twenty-first century have changed the way business is done the world over.

Hergé’s books appear as a colourful panorama of human civilisation offering the reader both information and entertainment in a most unobtrusive way

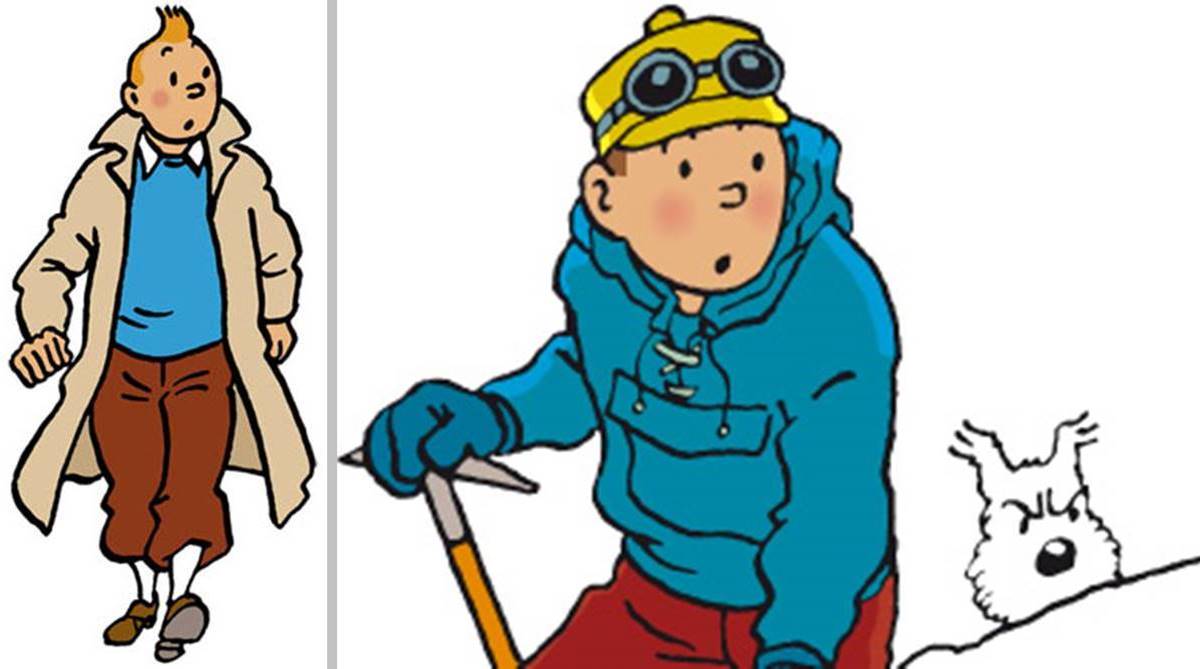

Tintin strips could not be continued after its creator Herge’s death. (Photos: Tintin.com)

It is celebration time for comic-book and graphic-novel lovers the world over. One of their all-time favourite characters, Tintin — a young reporter famed for his exotic adventures exposing skullduggery across the world and recognised for his trademark quiff and wire fox terrier Snowy — turns 90 this year. His hometown Brussels, just like many other cities in Europe and elsewhere, is buzzing with programmes that pay tribute to the evergreen creation of Herge. Wherever you go in Belgium today, the golden-tufted young reporter, the hero if Tintin comics, will hail you.

Belgium is celebrating the 90th anniversary of one of its most popular exportable products in a lavish way. There are souvenirs galore, and stamps, mementos and posters sparkle with the picture of the king of comic strips. All this love’s labour proves beyond doubt that Herge’s work will endure.

Advertisement

There are certain characters in fiction upon whom vagaries of time can leave hardly any marks, and all of them are known even to the man in the street. Of these, mention can be made of Shylock, Romeo, Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan and Tintin. If Shylock represents greed, Romeo stands for love; if Holmes represents modern detection, Tarzan stands for jungle adventure.

Advertisement

Last but not the least is Tintin who represents both adventure and boyhood curiosity, and in whom we find both sharp intelligence as well as youth’s fallibility — a charming figure bent on unravelling a mystery with dogged tenacity and untiring aplomb. Although Tintin saw the light of the day 90 years ago, when his creator Hergé began to publish Tintin comics in Le Petit Vingtieme from January 1929, the young reporter’s popularity has shown no sign of wane till date.

READ | The Tintin saga continues

For such a perennially young man, always in a hurry to right the world’s wrongs, it may however be strange to hear that Tintin has spent nine decades fighting bad guys around the world. From his earliest adventure in 1929 in the land of Soviets to report on the excesses of Stalinism, the young journalist’s exploits have been translated into 70 languages, and at last count sold more than 20 million copies around the world.

What accounts for the great popularity of Tintin books is, however, not merely the lovable character of the golden-tufted boy, but also a host of other funny characters like the mercurial Captain Haddock, the ever-failing detective duo Thomson and Thompson, the cute, little dog Snowy, the hard-of hearing scientist Professor Calculus, and the greatly arduous singer Madame Castafiore.

Tintin’s world seems to be the wonderland of Peter Pan where nothing changes. Wherever Tintin goes — be it a glitzy European city, the Arabian Desert, under the sea, in the land of mountains, or even the moon, readers wait for another tour de force from the boy reporter in his mysterysolving or crime-busting mission. Down the years, Tintin has achieved such great popularity that once Charles de Gaule famously said, “My only international rival is Tintin. We both are little people who are not afraid of big ones”.

Tintin’s creator, George Remy, or Hergé, drew wonderful sketches right from his childhood. His first illustration was published in his school’s scouts’ magazine, Jamais Assez. At 16, Herge illustrated the cover of the Belgian magazine, Le Boy Scout Belge. In 1926, Hergé presented his very first comic strip in this paper, illustrating daring adventures of a tiny boy scout, Totor, who is, in a sense, the predecessor of Tintin.

The young Belgian reporter’s first adventure was set in Russia where he encountered the ruthless Bolsheviks. The anti-communist flavour of Tintin in the Land of Soviets has much to do with the conservative, Roman Catholic standpoint of the Siecle magazine where Tintin strips were published.

The paper used to call itself “Catholic and National Newspaper of Doctrine and Information”. So Hergé was virtually forced to send Tintin to the communist land to caricature the Bolsheviks and portray their brutal methods of ruling the country. Although Hergé called this first Tintin adventure his “sin of youth”, controversy raged on, especially because of Hergé’s closeness to Degrelle, who later became the head of the fascist party of Belgium. Yet, despite the lack of finesse and subtlety in the finished work of Tintin in the Soviets, much of Herge’s criticism of Soviet corruption has stood the test of time. As The Economist observed in 1999, “The land of hunger and tyranny painted by Herge was uncannily accurate, even though he had never been there.”

READ | From Howrah to Darjeeling, Tintin stays on in Bengal

But Hergé incurred criticism not only for a single book, or for any particular relationship. There are a few Tintin books where critics have found racist elements. In the book, Tintin in Congo, Africans have been presented in less than-flattering light and the whole text seems to vindicate the ruthless rule of the whites over the black and native inhabitants of Africa. Hergé himself was aware of the prejudiced attitude of the book. So he wrote, “For the Congo as with the Tintin in the Land of Soviets, the fact was that I was fed on prejudices of the bourgeois society in which I moved… It was 1930. I only know the things about these countries that people said at that time – ‘Africans were great big children…. Thanks goodness for them that we were there…’ etc. And I portrayed these Africans according to such criteria, in the pure paternalistic sprit, which existed then in Belgium”.

Critics also came down heavily on Tintin’s thoughtless killing or torturing of wild animals, which Hergé seemed to offer to the adventure-loving young readers. Some scenes that present Tintin as killing timid antelopes, or stoning wild buffaloes, or drilling dynamite sticks into a rhinoceros’s body are truly appalling. Hergé himself was apologetic about it, “I felt remorse for having killed or caused to suffer too many animals in Tintin in the Congo.”

Some elements in this book are truly offensive to the black people. In it, black people are presented as possessing really low levels of intelligence, and are adept only in strife and violence. It is hinted in the book that they can only be guided properly by white men, and even a white dog can perform this task. In 2007, Commission for Racial Equality recommended a ban on the book, saying that such a book, so full of crude racial stereotypes, can get a place only in some museum to be displayed as obsolete, racist rubbish.

In The Blue Lotus, Hergé presented a picture of Japan’s aggressive imperialism, which was hell-bent on conquering neighbouring China in a brutal way. The Japanese diplomats protested to the Belgium foreign ministry against the book, while one Belgium general commented, “This is not a book for children … It’s just a problem for Asia”.

Although Hergé had previously held a prejudiced view of China which, according to him, “was peopled by a vague, slit-eyed people who were very cruel, who would eat swallow’s nests, wear pigtails and throw children into rivers”, his attitude to this country changed after coming into contact with a Chinese student of sculpture, Chang, who came to study at Academie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1934. Hergé wrote, “Chang was an exceptional boy… He made me discover and love Chinese poetry, Chinese writing… I owe to him a better understanding of the sense of things: friendship, poetry and nature”. In The Blue Lotus, Hergé gave ample hint to the fact that he was gradually coming out from portraying stereotyped characters to present more realistic persons in his book.

In spite of criticism and controversies, Tintin books enjoy popularity that is rarely achieved by any other comic strip. Hergé strips were the products of painstaking research, immaculate sketches, attractive cover-page illustrations, breathtaking plots, and charming characters. There are a number of reasons, from a comic book perspective, why Tintin books are important. Tintin was the first comic book series in Belgium and led directly to the beginning of the comic book industry there.

In France, meanwhile, Herge’s style, known as the ligne claire or “clear line” (a clearly drawn style with little shading), was hugely influential on comic book artists. Herge was an innovator in terms of using word and thought balloons, and as per recent research, he pioneered their use in Belgium. He also developed and expanded the use of symbols such as “speed lines” (the little lines that denote movement) in comics to give further meaning to his drawings.

Reading Tintin comics also develops visual literacy, which is becoming increasingly important in modern society. One of the central appeals of Herge’s work is its relish for Tintin’s own daring-do, the character pursuing Holy Grails, Maltese Falcons and Hitchcockian MacGuffins from Tokyo to the Andes, navigating a world of spies, gangsters, dowagers and aristocrats.

The Dalai Lama conferred “Truth of Life Award” to the Hergé foundation for the book Tintin in Tibet. This is a unique incident when a religious leader honours the creator of comic strips.

Apart from this award, Hergé and the Hergé Foundation received many awards like the Swedish government’s Adamson Award, and in 2003 Comic Book Hall of Fame et al. Although Hergé has taken help from many books, in the field of story-telling we find a distinct individuality with the dialogue being grammatically correct, colloquial and humorous. All the characters have a marked individuality: Professor Calculus is filled with self-confidence; Castafiore’s utterances are full of feminine vanity and affectation; the two detectives are quite gullible although they pretend to be omniscient; one of Haddock’s specialties is his choicest expletives like “blistering barnacles” and “thundering typhoons”.

In Tintin books, we get a host of issues related to life and knowledge — science fiction, supernatural events, politics, crime, archaeology, arts and culture, human rights and many other topics. No other comic strip hero has had to go through so many different types of adventure — some take place in polar regions, in desert lands, or in the land of aborigines, while some others take place in the land of Pharaohs or in the snow-capped Himalayan region.

Although Tintin’s creator had got help from the artists in his studio in the matters of garments’ design, background, sketches of cars and planes and other things, Herge’s presence was indispensable in the matter of creating major characters. Therefore, Tintin strips could not be continued after Herge’s death in 1983. Herge once wrote, “There are certainly a number of things which my collaborators can do without me and many that they can do better… but to breathe life into Tintin, Haddock, Calculus, the Thom (p) sons and the others, I believe that only I can do that. Tintin is me, as Flaubert said, ‘Madam Bovary c’est moi!’ It is highly personal work, in the same way a painter’s or novelist’s. If others were to continue Tintin, they might do better, they might do worse. One thing is certain, they would do it differently and so it would not be Tintin any more”.

Tintin strips ended in 1976. In his books, Herge nicely mixed the late 19th and early 20th century settings and issues with those of his time. If there were the old dynasties of Europe, we also have here the oil barons of his and our times. Herge’s books appear as a colourful panorama of human civilisation offering the reader both information and entertainment in a most unobtrusive way.

Last but not the least, in Tintin, every reader finds his boyhood spirit of adventure and with whom he can set off for a long journey to a distant land that involves both pleasure and perils.

Advertisement