Cold storage association demands storage rent rise from govt

West Bengal Cold Storage Association held their 60th annual general meeting on Wednesday.

An ongoing research project |involving the Universities of Calcutta and Oxford looks at the aristocratic zamindari homes of South Bengal — their unbridled affluence, inevitable decay and possibilities of resurgence.

Photo: SNS

West Bengal is not usually associated with stately homes, unlike Rajasthan or other parts of India. The state is known for the deltaic mangrove forests of the Sundarbans and the hilly areas of Darjeeling and Kalimpong while Santiniketan, Rabindranath Tagore’s “Abode of Peace”, offers cultural salvation to thirsty palates as does the annual Durga Puja each autumn.

That said there has been a recent surge of international interest in the erstwhile European settlements along the River Hooghly, namely Hooghly-Chinsurah, Chandernagore, Serampore, Bandel and Barrackpore cantonment. Murshidabad and Bishnupur are heritage towns that also attract visitors.

Advertisement

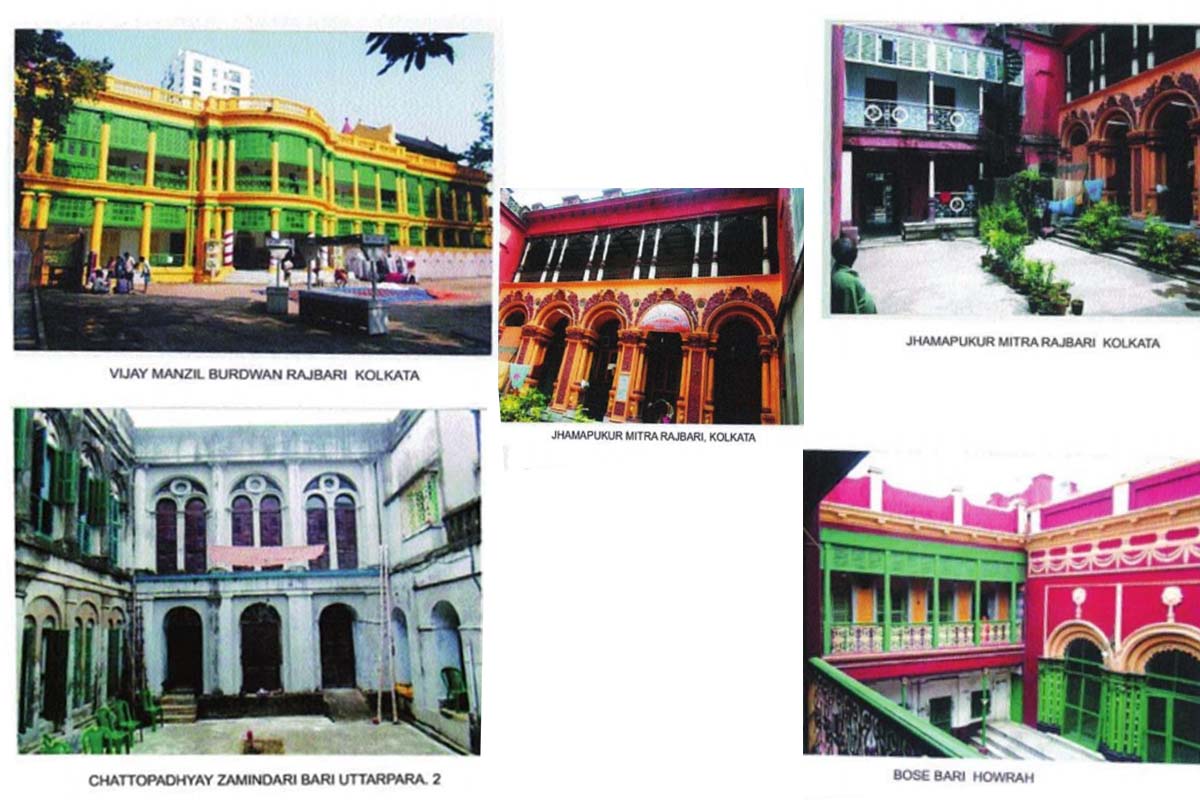

What of the plenitude of stately homes — zamindari houses, rajbatis and palaces — that dot the cultural landscape of rural and urban Bengal? The old houses of Kolkata have long attracted much attention, especially the time-worn icons at Sobhabazaar, Jorasanko and the Marble Palace on Muktaram Babu Street. However, the stately homes of the districts still have surprises in store for the adventurous traveller.

Advertisement

“Stately Homes of South Bengal” is my ongoing research project at the Centre for Urban Economic Studies, University of Calcutta and studies the conservation, regeneration, urban and regional development of the districts of the southern area of West Bengal, south of the Ganga, in addition the Kolkata Metropolitan Area. It is focused on the palaces, zamindari stately homes and Kolkata town houses, villas and palaces of the landed aristocracy in an area that had declined economically from about 50 years ago but will rise again. It involves 60 stately homes, two or three in every district, including 35 houses in the districts taken together while 25 houses are being looked at in Kolkata.

The fieldwork commenced about a year ago and I have so far completed a coverage of the zamindari buildings and palaces of six districts, including Jhalda and Hensla Rajbatis in Purulia, Halisahar Rajbati and Taki in North 24 Parganas; Birbhum District, namely, Hetampur, Raipur, Taltore and Surul Rajbatis, the Gani family zamindari building in Dhaniakhali, the Mankundu Khanbari, and Bansberia Deb Roy Garhbari in Hugli, Narsing Dattabari and Bosebari in Howrah as well as Mahishadal, Tamluk and Kelomal in East Medinipur. As far as Kolkata is concerned, I have interviewed and surveyed the Narail zamindari family, the Santosh, Jhamapukur, Mullick, Sil and Thanthania Laha rajbaris and Wasif Manzil, the home of Shahanshah Mirza, descendant of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Lucknow. I plan to complete my field work in the districts between October and January and the project should be complete in two years.

The project has several advisors, including Partha Ranjan Das, conservation architect and member, West Bengal Heritage Commission; professor Chitta Panda, historian and former secretary-curator, Victoria Memorial Hall, an authority on zamindari, and senior geographers from my department at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom, with reference to conservation, planning, urban and regional development.

It takes heed of the Rajasthan model and the UK stately homes, the UK National Trust and the Oxford Preservation Trust and Green Belt network. I would particularly like to appreciate the interest of Dr Ian Scargill, my supervisor at Oxford and urban geographer, and Professor Andrew Goudie, my former head of department and emeritus professor of geography, Oxford. My supervisor at Calcutta University, Suprova Ray, is taking a keen interest as well.

The project also looks at pictorial views and colour and black-and-white photographs, including the collections of the British Library and the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), London. The research involves a detailed questionnaire survey by quota sampling of each family studied with interviews and photographs of exteriors, interiors, old buildings, family views and social events.

The project will probably culminate in my seventh book and, to the best of my knowledge, is the first research project on the subject. Both the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage and the Centre for Built Environment, Kolkata, are involved. The contemporary development of urban and rural areas is studied, taking the stately homes as focal points following the UK National Trust and Rajasthan models.

The cultural landscape produced by humankind on the surface topography of the Earth includes buildings, transport arteries and other forms of social spaces. The distinctions in the significance and physical appearance of such cultural forms are generally due to differences and dichotomies in the extent of power in the control of individuals or social groups.

Buildings and power have been the subject of extensive research in the Anglo-American world (for example, Thomas A Markus’s Buildings and Power, Routledge, 1993), but recent research on similar themes in India has been relatively restricted to travel accounts and occasional studies of important buildings, palaces and forts in particular cities, towns and citadels. This research attempts to assess the nature, condition and future usage and importance of stately homes, mostly zamindari and princely palaces and buildings in South Bengal. The subject has not been considered in much detail by geographers or in the context of the work of academics such as Michel Foucault, Henri Lefebvre, David Harvey, Denis Cosgrove, Stephen Daniels and Nuala Johnston. It should therefore be of academic and practical interest, especially in post-Communist West Bengal after 2011.

Data sources include historical texts on land records, zamindari and land revenue accounts as well as the district gazetteers of Bengal of British and contemporary times, geographical texts on the physical and social landscapes of south Bengal, maps and photographs. To date, the only relevant texts are by art historian Joanne Taylor (Forgotten Palaces of Calcutta, Niyogi, 2006) and The Great Houses of Calcutta by Joanne Taylor and architect Jon Lang (Niyogi, 2016). The social and cultural historical geography of south Bengal with Kolkata as a pivot from the 17th century onwards and particularly from the era of the 19th century Bengal Renaissance, the babu culture, Tagorean culture, the patronage of aristocratic pursuits such as the arts and hunting, sport and game, the development of alternative seats of Bengali upper class power in urban forms such as the hill stations of Darjeeling and Kurseong, tea plantations and the club culture of Kolkata, Darjeeling and other cities are discussed.

The research studies rural and urban employment, crafts development and transport connectivity, agrarian economies and local political situations. It focuses on the urgent need to conserve and preserve these vital heritage structures as part of state and national cultural heritage, which could refuel the economy and earn revenue, including foreign exchange, as well as investment in urban and regional development planning as a part of sustainable development from heritage tourism and cultural, urban and social regeneration with Indian, British, American and other international expertise and consultancies. There is also ample scope to replicate the model of development in east and north West Bengal as well as study its scope in Bangladesh, where several of the Bengal aristocratic families originate and have links, such as the Teota, Santosh and Tagore dynasties.

Some of the stately homes of south Bengal have already been redeveloped as heritage hotels (Itachuna in Hooghly and Bawali in South 24 Parganas), homestays (Balakhana in Nadia and Amadpur in East Bardhaman) and museums (Mahishadal), while others are used as venues for weddings (Vijay Manzil: Burdwan Rajbati), parties and conferences or educational institutions (Hetampur, Birbhum and Burdwan Palace, East Barddhaman). I am studying these in detail and also exploring the possibility and feasibility of extending the concept of heritage hotels, handicrafts emporia, cafes, restaurants, souvenir shops and museums with better regional roads in a wide-ranging context, and subsequently the rest of West Bengal with possibilities for replication in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

The research is turning out to be fascinating and I have learnt much about the impact of Rajput and other royal dynasties in the western areas, including the Malla Debs of Jhargram, the Singh Deos of Purulia and Singh Roys of Chakdighi, East Barddhaman. Raja Vikramaditya Malla Deb of Jhargram told me about the need for governmental support, better roads and other aspects for his heritage palace hotel. Ronodhir Palchoudhuri of Balakhana and Ambreesh Singh Roy of Chakdighi are developing their properties. The Mahtab family of Burdwan has huge estates still and has gifted their main rajbati in Burdwan to the university. The Singh Deos of Jhalda are descended from an old Rajput warrior clan dating back to 80 AD who stopped off at Jhalda on their way to Puri when a queen gave birth to the future dynastic head.

Not all the stately homes originate with Lord Cornwallis’ Permanent Settlement of 1793. The Banerjee Halisahar Rajbati dates back to Mughal times. Some of the stately homes originated in wealth accumulated in trade between families and the East India Company, such as the Sarkars of Surul Rajbati, Birbhum, whose ancestors traded with John Cheap, an English agent. Ramnidhi Chattopadhyay and Joy Krishna Mukherjee of Uttarpara were wealthy zamindars. The Mukherjees of Tala and Mitras of JhamapukurShyampukur were descended from wealthy businessmen and traders who had links with the British. Sita Ghosh, descendant of Raja Digambar Mitra of Jhamapukur, took me to her ancestral homes as well as the Pathuriaghata Ghosebari, which could be a charming heritage precinct. It should be noted that not all the families with stately homes want intrusions into their privacy with visitors.

Advertisement