Indian Shakespeare~I

We call him Shakespeare of India. We regard him as the greatest poet and playwright of ancient India. The world recognises him as one of the greatest poets of all time.

Of the numerous mind-boggling ifs in English literature, a truly notable one is what Charles Lamb might have been like as man and writer if in a fit of madness his sister had not slain their mother when he was only 21.

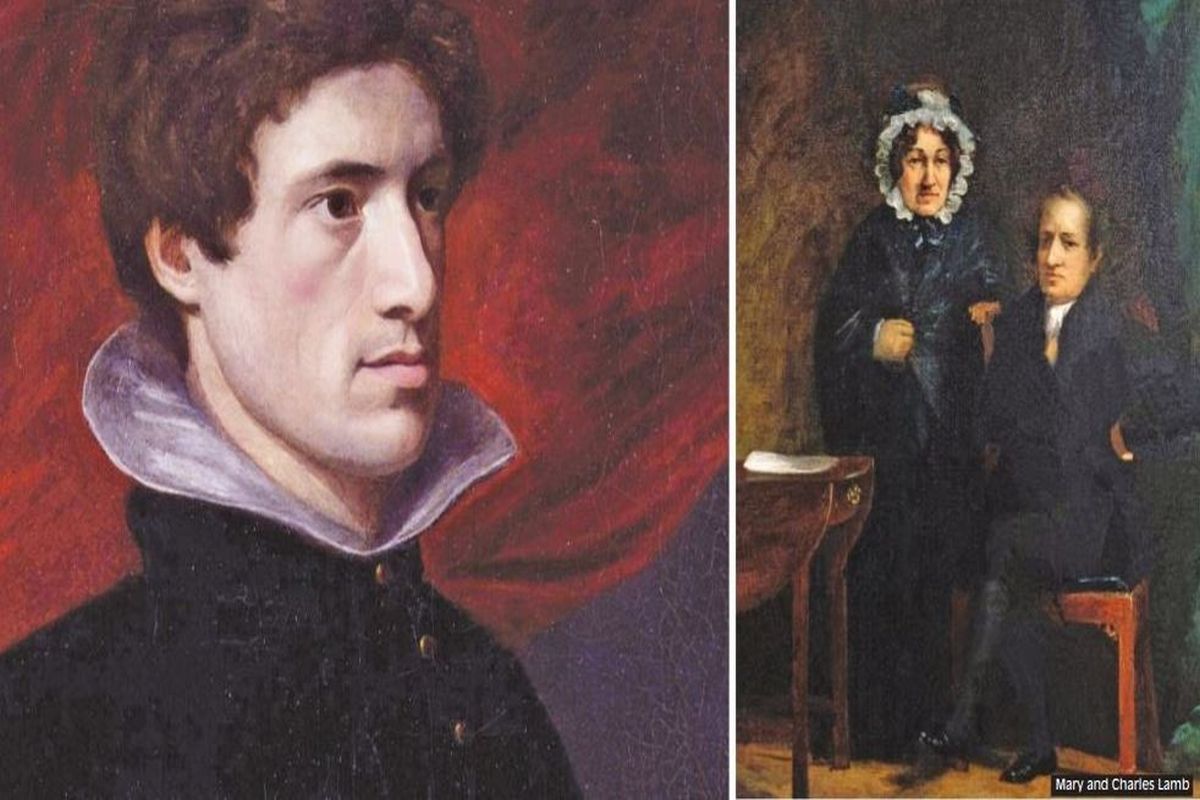

Mary and Charles Lamb.

Is there any limit to the list of innumerable “ifs” and “buts” in our life or in the world we inhabit? From experience, one can fairly say, no. Life does not always move the linear way and the hand of destiny often comes in the way of wish fulfilment.

And when it comes to literature, this amazing list baffles readers and critics ad infinitum. What if John Keats lived a long life like William Wordsworth or Samuel Coleridge’s Kubla Khan had been finished? The Romantic period in English literature, in particular, is full of such strange yet interesting “ifs” and “buts”.

Advertisement

Of such numerous mind-boggling “ifs”, a truly notable one is what Charles Lamb might have been like as man and writer if in a fit of madness his sister had not slain their mother when he was only 21. It is quite well-known that the “gentle Elia” the world loves was the product of ungentle and terrible events. He was the stepchild of a calamity as bloody as any to be found in the most bloodstained Elizabethan dramas of which Lamb was later to become a champion. To a tragic extent, Lamb’s life and hence Elia’s character was carved out for him by the knife, which poor deluded Mary drove straight and deep into their mother’s heart. Surely never in the strange annals of authorship has the world gained so much in pleasure or an innocent man lost more in freedom than in the instance of the catastrophe, which resulted in Lamb becoming the most beloved bachelor of letters literature has produced.

Advertisement

It was the afternoon of 22 September 1796. Lamb quit his desk at the East India Office and started to walk home through the London he loved, yet his mind was full of worries. His sister Mary, 10 years his senior, had already shown symptoms of insanity. In any case, Mary’s condition was sufficiently disturbing to have sent Lamb, on his way to walk that very morning, in search of a doctor who was not to be found. Aware though he was of the gathering clouds, Lamb could not have been prepared for the violence of the storm, which had broken out in the house where he lived with his old father, his invalid mother, his sister, and his Aunt Hetty.

The sight, which Lamb beheld when he opened the door, was of tabloid gruesomeness. Above the bustle of Little Queen Street, he may have heard the cries of his father and the shrieks of Mary and her apprentice as he approached his home. The room in which the table was laid for dinner was in turmoil. Charles’s aged aunt was unconscious on the floor, “to all appearance like one dying”. His senile father was bleeding from a wound in his forehead. His mother was dead in a chair, stabbed to the heart by Mary, who was standing over her with the case knife still in her hand. Lamb arrived only in time to snatch the knife from her grasp.

What had provoked this scene no one knows. Perhaps as a professional seamstress, Mary had been overworking, and the stress of a dependent household had become too great for her. Perhaps the final straw had been the additional cares, which had come her way because of the leg injury suffered by her brother, John, her elder by a year and a half. Perhaps, as moderns have hinted, an ugly long-suppressed animosity between her and her mother had at last erupted. In any event, Mary had had an altercation with the young woman who, in her mantua-making, was her helper. Mary had reached for the knives and forks on the table, throwing them at this frightened girl in the hope of driving her from the house. It was one of the forks thus thrown, which had struck her father.

Her mother might have been spared had she not attempted to intercede in the apprentice’s behalf. “I date from the day of horrors”, wrote Lamb to Coleridge soon after the disaster. Although by this he meant merely to place in time events described in his letter, he unwittingly summarised the rest of his adult life. To these sensational occurrences, which cost him dearly, we owe, in part at least, the writer we cherish as one of the least sensational of authors. For the next 38 years, Lamb lived a gallant and, on the whole, a cheerful prisoner to the happenings of that fatal afternoon. In no sense of the word a tragic hero, he emerged as the hero of a tragedy. We pity him the more because he was without self-pity

There are people, luckless mortals, who by the injustices of circumstances or because of a certain granite in their character, are doomed to be caryatids for the suffering of others. Charles Lamb was one of them. He could have fallen back on the law and allowed his sister to be committed to a public insane asylum. He could have walked out on Mary. He could have done what his elder brother John did and wanted him to do. Yet even when John washed his hands of the whole problem, Lamb was able to rise, “not without tenderness”, to his brother’s defence. He knew John to be “little disposed … at any time to take care of old age and infirmities”. Charles went so far as to persuade himself that John, “with his bad leg, had an exemption from such duties”

From the outset, Lamb was determined — regardless of the sacrifices — that Mary should not be sent to an asylum. Instead, he took full responsibility for her. Because of this utter devotion, his own life was altered inescapably. Had it not been for Mary, age would not have fallen so suddenly and totally upon him.

Without her, we might be able to imagine Lamb as a young man rather than always picturing him as a smoky and eccentric oldish fellow, settled in both his habits and his singleness, whose youth had come to an abrupt end with his childhood. Without Mary, Charles’ dream-children would have been real. The “fair Alice W–n,” she of the light yellow hair and the pale blue eyes for whom he claimed to have pined away seven of his “goldenest years,” might have been the “passionate… love-adventure” he once described her as being instead of a reference, true or fanciful, which biographers have been unable to track down. He might not have waited so many years to propose to Fanny Kelly, the actress with the “divine plain face” and Fanny might even have accepted him

How much did Charles lose in terms of happiness in life or of literary achievements as fate struck him? Without his “poor dear dearest” Mary, Charles might have continued longer to try his hand at poetry and not so soon have “dwindled into prose and criticism”. His spirit would have been gayer, his laughs less like sighs. He might not have been so “shy of novelties, new books, new faces, new years.” The present, not the past, might have been his delight. He would not have been driven, as driven he was by the events of that appalling afternoon, to find happiness by thinking back to happier days.

The texture, the range, the very tone and temper of his work would have been different. From the moment of his mother’s murder and the time that he stepped forward to become Mary’s legal guardian, Lamb knew that he and Mary were “in a manner marked”. There was no hushing their story. No shelter could be found from the nudgings, whisperings, stares, and embarrassments it provoked. Fortunately, theirs was a relationship based upon more than the perilous stuffs of gratitude or an embittered sense of obligation. They were united not only by misfortune, but by shared tastes and minds which, in spite of dissimilarities, were complementary. Their devotion to each other was genuine and abiding. It shines through their letters.

In a letter to Coleridge, Lamb wrote, “Of all the people I ever saw in the world my poor sister was most and thoroughly devoid of the least tincture of selfishness — I will enlarge upon her qualities… in a future letter for my own comfort… and if I mistake not, in the most trying situation that a human being can be found in, she will be found uniformly great and amiable”. No brother and sister in history are more inseparably linked than Charles and Mary. To Lamb, their life as old bachelor and maid was “a sort of double singleness”

Through its knowledge of Charles as the “gentle Elia” the world does Lamb an injustice. Gentle he was always with Mary and in most of his writings. It was, however, his strength, which enabled him to be gentle and not any softness that forced him into being so. “For God’s sake,” wrote Lamb to Coleridge, “don’t make me ridiculous any more by terming me gentle-hearted in print or do it in better verse… The meaning of gentle is equivocal at best, and almost always means poor-spirited”.

Lamb knew that physically he was “less than the least of the Apostles”. But there was iron in his “immaterial legs.” His slight body contradicted the largeness of his spirit. The portion of the Earth that Lamb loved best was not green. He preferred cobblestones to grass. He was a city man if ever there was one; a cockney in every inch of his person. The nightingale never released a song so sweet to his ears as the sound of Bow Bells. The pleasure Wordsworth found in a daffodil, Lamb derived from a chimney- sweep.

He dared to write to Wordsworth, of all people, “Separate from the pleasure of your company, I don’t much care if I never see a mountain in my life.” Nature to him was “dead”; London, living. The sun and the moon of the Lake District did not shine for him as brightly as the lamps of London. He, to whom much of life was denied, often shed tears of joy on his night walks about London at encountering so much life.

Since truth to Lamb was as personal as everything else, facts enjoyed no immunity from his prankishness. His love of mystification was one of the abidingly boyish aspects of his character. It pleased him in his essays to mislead his readers by false scents; to write Oxford when he meant Cambridge; to make Bridget his cousin, not his sister; to merge Coleridge’s boyhood with his own; or to paint himself as a hopeless drunkard when, as a matter of fact, he was a man who, though he loved to down a drink, was seldom downed by drinking.

Lamb’s essays are but the “shadows of fact,” yet Lamb was present in their every phrase and sentence. Yet, in the essays, he was not the whole man, though an important part of him was present. The highly self-conscious artist we cherish as Elia emerged late in Lamb’s life as the flowering of his varied career as a professional writer. By that time Lamb had long since mislaid, except for album purposes, the poet of slight endowment he had started out by being. Years before, too, he had discarded the novelist whose all but the nonexistent talent for narrative stamped Rosamund Gray and his contributions to Mrs. Leicesters School as no more than apprentice work. He had also buried the dramatist with “no head for playwriting” whose blank-verse tragedy, John Woodvil, was but the feeblest of Elizabethan echoes, and whose little farce, Mr.H. was so disastrous a failure that its author had joined the hissing. In the same way, Lamb had outgrown those un-Lamb like Tales from Shakespeare upon which he had collaborated with Mary. Although he had predicted such a potboiler would be popular “among the little people”, he had never guessed how enduring its popularity would prove among those grownups of little courage who, apparently, are grateful for anything which spares them Shakespeare in the original.

But the same Lamb who had abandoned poetry early in his career wrote as a poet when he was at his best as a critic or correspondent. The stuttering, jesting, smoking, drinking little fellow, valiantly linked to Mary, was little in an abidingly big way. He was big of heart, large of mind, and unique in his endowments. Victim of life though he was, he was never victimised by it. He lived an interior life externally. Perhaps Walter Pater, another stylist, wrote the best summary of Lamb in these words, “Unoccupied, as he might seem, with great matters, he is in immediate contact with what is real, especially in its caressing littleness, that littleness in which there is much of the whole woeful heart of things, and meets it more than halfway with a perfect understanding of it.”

Advertisement