Divya Dutta on industry sexism: “Still a long way to go”

In a recent chat with IANS, the actress got real about gender disparity in the film industry, historical storytelling, and the exciting projects she has lined up.

Regretfully, not too many are aware of these early women filmmakers, as their work is rarely screened or even referred to by the media.

SANJUKTA DASGUPTA | Kolkata | March 4, 2024 4:14 pm

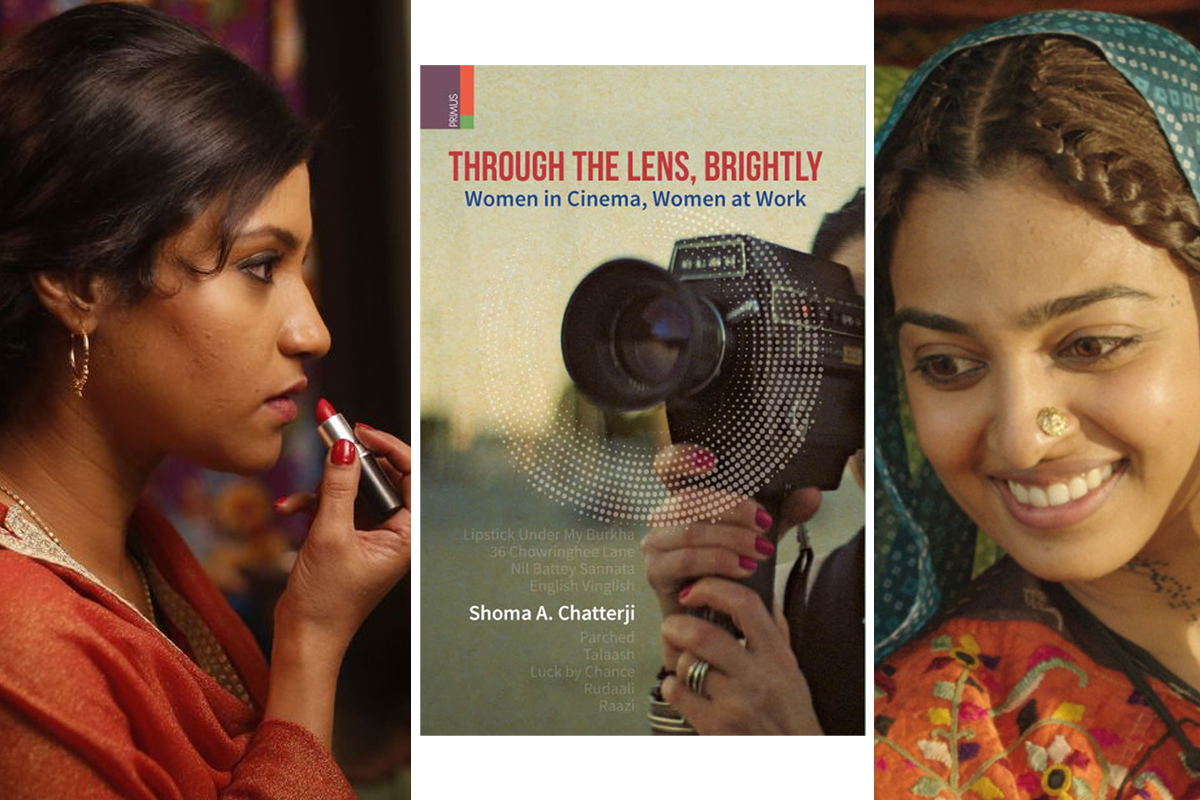

Ace film critic, writer and translator Shoma A Chatterji’s recent book on Indian women filmmakers and their representation of working women in their films in varying ecosystems is an outstanding study of the gendered patriarchal structures that women film directors have deconstructed since the 20th century. Through the Lens Brightly Women in Cinema, Women at Work is a worthy addition to film studies as it provides a comprehensive overview of the pioneer female film directors who began setting up film companies and directing films as well in British India. The historicising of the significant contribution of women filmmakers during the colonial period opens up windows of perception about the confidence of women directors in taking on the onerous task of filmmaking in a predominantly male-dominated film industry. Regretfully, not too many are aware of these early women filmmakers, as their work is rarely screened or even referred to by the media.

Interestingly, the very first chapter of Chatterji’s book, titled “The Evolution of Women Directors in Indian Cinema”, begins with fascinating details about Fatima Begum, who was the very first woman director who had begun her career in the era of silent films. In 1926, she set up her own film company, Fatima Films, and eventually went on to direct a total of nine films in all. Moreover, Fatima broke free from the practice of sustaining the hegemonic presence of mythological films and moved over to the domain of making fantasy films that were inspired by the Arabian Nights. A remarkable attribute of the films directed by Fatima was her shifting of focus from a male protagonist to a female protagonist. In the 1920s, this was truly a remarkable reversal of the stereotype of the active male-doer and the passive female-preserver of customs and traditions.

Advertisement

Also, in 1936, Jaddanbai, mother of the renowned film heroine Nargis, set up the Sangeet Film Company. Furthermore, she was the first woman to set up a film production company. She not only produced and directed films but also acted and sang in them, and she is known to have played a double role in one of her films. In the mid-1930s, with talkies taking over from the silent film era, another stalwart woman director, Shobhana Samarth, not only acted in films but was a successful film director and producer. Film critic Chatterji provides interesting biographical details about these early women filmmakers, their families, and their daughters who became actresses, such as Nargis, Nutan, and Tanuja, among others. In fact, the archival research by Chatterji gestures towards the necessity of producing biopics of these pioneer women filmmakers, who were undoubtedly game changers. She also refers to Bengali women film directors Manju Dey and Arundhuti Devi and their stellar contribution to Bengali language films through their contributions as versatile actors and talented directors.

Advertisement

Despite the evidence that women directors of repute can be located from the 1920s onwards, almost 100 years later, in 2024, the contribution of women filmmakers still remains in the margins. A film critic had remarked in a Filmfare article about the systematic marginalisation of women filmmakers, as she commented, “While female directors and executives in Hollywood continue to fight for equal representation in the film industry, female filmmakers in India are waging a similar battle against their own country’s long-standing patriarchy. Women filmmakers are challenging the status quo across the wildly diverse landscape of Indian cinema, spanning countless genres and nearly a dozen languages, whether at the art house, regional cinema, or within mainstream Bollywood. However, even by the still unequal international standards, female representation behind the camera remains abysmally low.”

Chatterji’s book is divided into three parts. The first part, divided into two chapters, provides historical data about the early women filmmakers, followed by some interesting inputs about 20th-century Assamese, Marathi, Bengali and Kannada-language women filmmakers who had been remarkably successful in the making of regional films that won recognition and awards. In the concluding section of this chapter, Chatterji refers to the diasporic filmmakers Deepa Mehta, Mira Nair, Gurinder Chadha, and Tanuja Chandra. She comments, “Films by women are distinguished for their subtle accommodation of gynocentric perspectives and interpolation of issues related to Indian women’s lives, along with a critique of social customs and taboos arising from prejudicial cultural practices.”

The second chapter in this first part deals with women and work, the challenges faced by working and non-working women, unpaid labour, reproductive labour entailing the bearing and rearing of infants, and caregiving. Chatterji also briefly refers to the falling ratio of women workers in the organised sector and the employment of women in the unorganised sectors, mostly due to economic distress rooted in severe patriarchal ecosystems.

The second and third parts of this book include a riveting gender-specific critique of filmmaking by women and a content analysis of selected women-centric films. In their conception and visualisation of the female protagonists by women filmmakers, the underpinning is feminist, but the overt mode often gestures towards conciliation, appeasement and compromise in one way or another. In Part Two, chapters one and two deal with Aparna Sen’s classic film 36, Chowringhee Lane, about an elderly Anglo-Indian teacher, and Kalpana Lajmi’s Rudaali, which focuses on a professional mourner in rural India. Both of these films are outstanding in their representation of the female protagonists, maintaining the pertinent and permanent value systems that are showcased with remarkable poise and finesse.

Part Three of the book comprises seven chapters that render a close reading of the feminist film texts and that raise and resolve questions about women and paid work that have hitherto been elided in films made by women. This is undoubtedly a paradigm shift in the representation of women as paid labour that debunks the stereotype that for women’s labour, the defining phrase is the much-glorified concept of the exclusive labour of love. The films Luck by Chance, English Vinglish, Taalash, Parched, Nil Batti, Sanata, Lipstick Under My Burkha and Raazi by Zoya Akhtar, Gauri Shinde, Reema Kagti, Leena Yadav, Ashwiny Iyer Tiwari, Alankrita Shrivastava, and Meghna Gulzar, respectively, have triggered new vistas of perception and optics about the politics and problematics of representing women as the Foucauldian desiring subjects in feature films.

Interestingly, Shoma Chatterji’s incisive observation of the rural women represented in the films directed by women deconstructs many myths about the self-effacing, illiterate, and voiceless women who reside in Indian villages. Referring to the film Parched, directed by Leena Yadav, Chatterji comments, “Parched throws up an outstanding and unconventional vision of the sex-starved lives of these women, across age, occupation, courage, or the lack of it. These colourful women derive vicarious thrills by talking dirty, talking sex in their own way…It destroys the myth of unlettered women being naïve and simple.” Elsewhere, Chatterji further comments, “The film is a feminist pitch against patriarchy that defines a woman’s life, its double-edged title as sharp as a knife that cuts both ways.”

This remarkably exhaustive and intensive critical assessment of the film texts created by women filmmakers by the redoubtable film critic Shoma A Chatterji, spanning the wide trajectory from the colonial period to the postcolonial and thereafter the era of globalisation, will be a boon for researchers, students and teachers of South Asian film studies, gender studies and cultural studies. Moreover, Through the Lens, Brightly Women in Cinema, Women at Work can be used as a core text or a reference text in women’s studies research centres, globally and locally.

The reviewer is professor and former dean, department of English, University of Calcutta

Advertisement

In a recent chat with IANS, the actress got real about gender disparity in the film industry, historical storytelling, and the exciting projects she has lined up.

'Dacoit - Ek Prem Katha' is a pan-India action drama that follows a convict's quest for revenge against his betraying ex-lover. The film blends intense action with emotional twists.

Anupam Kher teams up with Prabhas for an upcoming film directed by 'Sita Ramam' filmmaker Hanu Raghavapudi. It is backed by Mythri Movie Makers.

Advertisement