Meticulously woven together, this comprehensive biography of Naina Devi delves deep into the vicissitudes of life that wrought upheavals into the protagonist’s existence and she had to grapple with the time and again.

Mathur has accomplished a commendable task with her fitting descriptions of the numerous, diverse people and unusual circumstances that impacted Naina’s life, while keeping her central character always firmly in place.

Advertisement

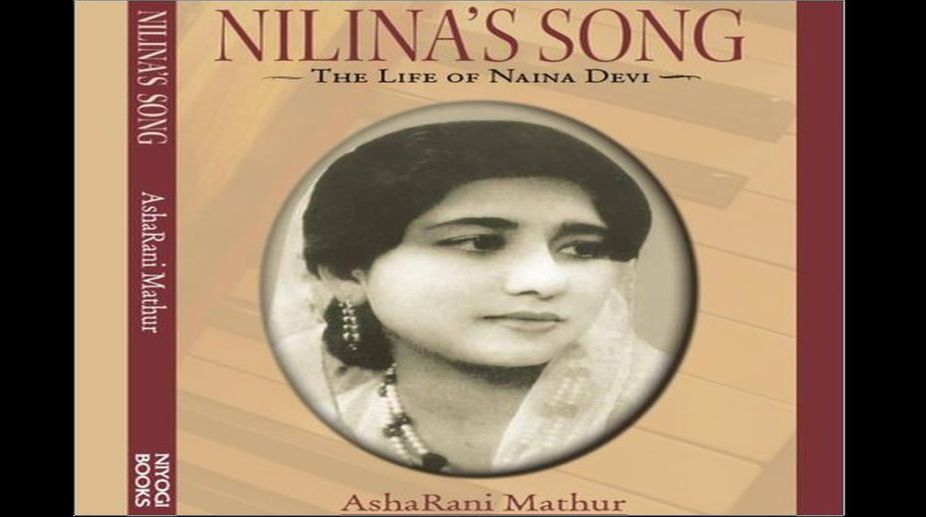

The jacket features an enchanting portrait of a young dewy-eyed Naina Devi; her innocent face looks soft and vulnerable, expressing unfathomable longing.

The book simultaneously explores the social fabric of India of the 20th century, chronologically revealing the lives of dynamic reformers who changed the course of a British dominated country to the time of the post-Independent era.

Divided into the three main segments that reveal the transformation of Nilina into Nina and finally to Naina, the book also features rare black and white photographs. Apart from those of Naina, many include eminent persons linked to her life, or with india of that era.

The reader gets an intimate picture as she evolves from a young girl in a sheltered and protected life to a mature woman who turned protector and offered refuge to needy musicians and artistes in her later years.

In the ‘Introduction’, Mathur describes how as the seasons changed, the garden in front of Naina Devi’s house was “transformed into a cultural canvas where musicians would throng to celebrate Chaiti…”

She writes: “Naina Devi was passionate about thumri and reprimanded the author when she referred to it as a genre of ‘light, classical music’. She rebuked her by saying, ‘There is nothing light about it. The greatest thumris display and exact extraordinary “taiyyari”, the skill born of years of practice in their performance.’

The author initially faced ‘gaps’ when researching on Naina Devi’s life but these were generously filled with enthralling stories recounted by her sons, daughters, students, friends, and many others who treasured her charm, grace and compassion.

This is the evolution of a woman who turned into “three avatars”, reinventing and adapting herself through each phase she passed through three different personas ~ Nilina Sen, Rani Nina Ripjit Singh and Naina Devi.

Her story commences in Calcutta, then the ‘glittering first city of the Raj’ in the beginning of the 20th century. Nilina’s grandfather, Keshub Chandra Sen, was among the most prominent figures of the Brahmo Samaj; his mentor was Debendranath Tagore (father of Rabindranath Tagore), also a leading light of Brahmo Samaj.

Around 1875, Keshub Chandra Sen met Hindu mystic Shri Ramakrishna who affected him deeply with his concept of Motherhood of God. A rare photograph of the latter in a trance at the former’s house on 21 September 1879 captures the essence rather effectively.

Young Nilina’s home was steeped in music; she was being trained by the distinguished Girija Shankar Chakravarty. Married at a young age to Kanwar Ripjit Singh from the Kapurthala royal family in Simla, she now became Rani Nina Ripjit Singh. However, music was forbidden in the house and looked upon as the ‘art of tawaifs’ (courtesans) and her beloved passion had to be relegated to the backstage in her life.

But they made visits to Lucknow which she enjoyed. Nina’s heart, conditioned by the influence of her grandfather, Keshub Chandra Sen, responded to the ‘syncretic nature of the legacy of the Nawabs’, who understood that Muslim practices and Hindu practices could be harmonized. In her Lucknow house, Nina endeavoured to revive an old tradition of music.

There would be mujras where famed baijis of the city would entertain the men with their performances. On these occasions, Nina would listen intently from behind the chilman (screen) “soaking in every nuance of the songs, the gestures and expressions”.

After the performance, Nina would personally interact with the baiji and note every inflection and subtlety of Urdu diction. Indeed, a large part of the repertoire that Nina carefully built up over the years for her own performances was sourced right here, from these functions.

It also seeded in her a passionate interest in the tawaif, the baiji, the courtesan. She illuminated it very aptly in her own words on a paper she wrote in 1991: “Thumri is more suited to the female voice… and was performed by tawaifs and baijis from Banaras, Lucknow and Gaya.

It enabled them to musically emote the overwhelming injustice of their third-class status as artistes and human beings, and also act as spokeswomen for their more economically privileged sisters imprisoned in the zenana, whose menfolk come to the ‘kothas’ for an evening of diversion and entertainment.”

Words like ‘injustice’ and ‘imprisoned’ perhaps were references to her own memory of music in her life and its denial, of women who faced the heavy odds of society. However, tawaifs and baijis were a fading tradition even when Nina heard them in Lucknow.

She was a doting mother to her four children (Rena, Ratanjit, Nilika and Karanjit) and her family enjoyed an idyll life at Chapslee. But her world turned upside down when Rip, her husband, succumbed to cerebral haemorrhage.

She was just 32 when he passed away. To add to the trauma, her father-in-law turned against her and wanted custody of her children. Nina was looked upon as an ‘outsider of dubious intent’.

Fortunately, her old friend Sharda and her husband, CB Rao entered her life like guardian angels at this time and advised her, “You have such a beautiful voice. You can rebuild your life… You must sing.” Following their words, she auditioned for All India Radio and travelled to Delhi for the recordings. It was time for Nina to move on.

Her life changed dramatically and henceforth she took the name of Naina Devi ~ ‘seeker of music’. But she had to give up her palatial home in Simla for a tiny two-room apartment in New Delhi. And it was here, under trying circumstances that Naina finally found her true calling, when she was finally ‘liberated’.

A rented house for Bharat Kala Kendra on Pusa Road was also home to Naina (she stayed in two rooms in one part of the building) and was appointed Resident Director. The best part was it ensured endless music. The house hummed with soirees, with dance and music, as illustrious artists visited, stayed and taught many students, all activities of the Kendra.

The book is liberally filled with evocative black-and-white photographs that trace Naina Devi’s life through her youth to her last days. A special extract from her own article “Women in Traditional Media” presented at the ‘Empowering Women through Media’ in 1991, gives a stirring account of her perception of thumri, and why it is more suited to the female voice… (and) the reason why this was practiced by courtesans, tawaifs and baijis from Banaras, Lucknow and Gaya.

The unique life of this exceptional woman has been artfully illuminated through this book; her three charismatic avatars ~ as Nilina, then Nina and finally Naina Devi, when she could thrive in the melody of ‘thumri’, her lifelong passion and treasured dream.

The reviewer is Features Editor, The Statesman, Kolkata