In Varanasi, the holy city where the Ganges winds its way past time-worn ghats and ancient temples, a profound daily ritual takes place along its shores. This tradition, known as the cremation of bodies in Hinduism, is carried out by Doms, and is regarded as a sacred rite believed to free the soul, serving as a crucial step towards achieving salvation.

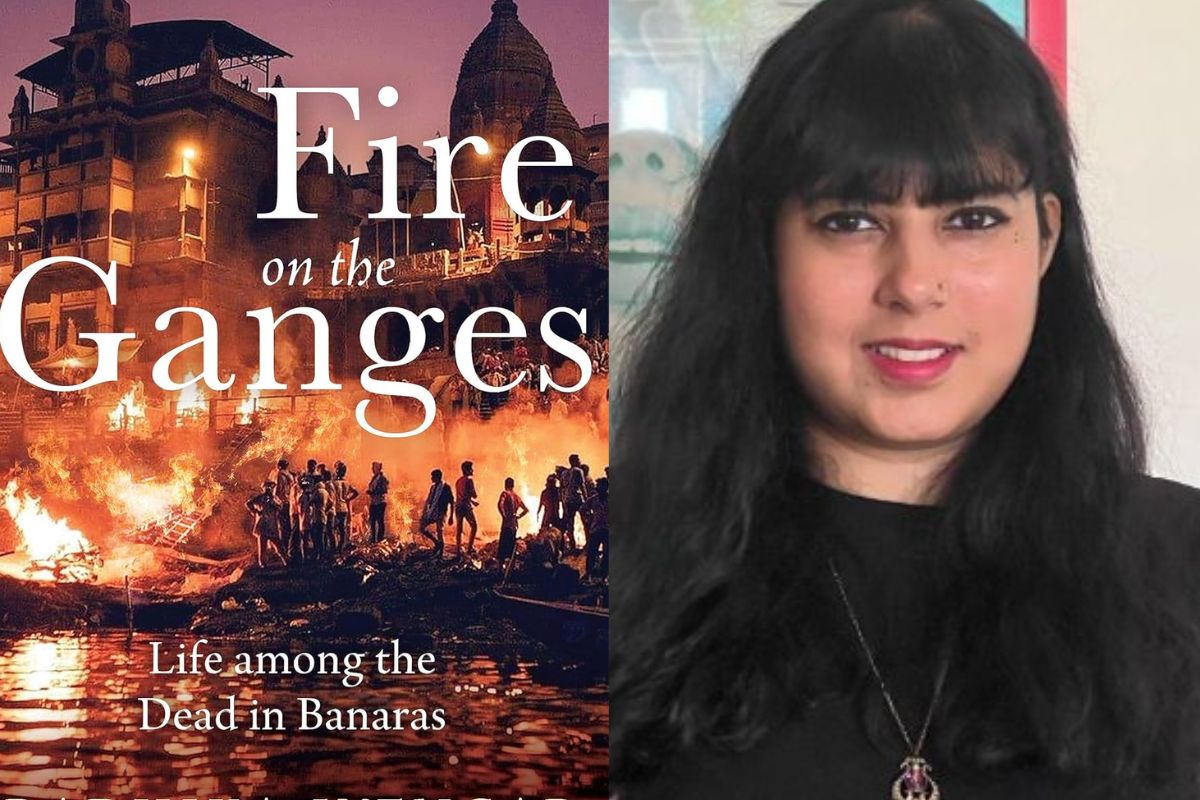

Journalist Radhika Iyengar’s debut book, Fire on the Ganges: Life among the Dead in Banaras, is based on the marginalised group of the Doms— the individuals responsible for cremating corpses in Banaras, and whose livelihood is intimately tied to the morbidity that surrounds them. Mandated with the solemn duty of performing Hindu cremation rituals, the Doms, branded as ‘untouchables’, find themselves relegated to the lowest echelon of the caste hierarchy. The right to aspire is a privilege denied to these members of the Dalit sub-caste. The scant semblance of life they experience is intricately intertwined with the pyres ablaze on the ghats of the sacred city, and their societal value is inexorably linked to the departed—quite literally deriving their social currency from the deceased.

Advertisement

Fire on the Ganges recently won the Kalinga Literary Award in the Youth category at the 3rd Kalinga Literary Festival Book Awards.

Speaking about her book, Radhika Iyengar sat in conversation with The Statesman at the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet.

Following are the excerpts:

Q. What led you to choose the Dom community for your focus?

During my Master’s in Journalism at Columbia University, I chose to write a thesis about the Dom community after reading an article about them. Despite limited information available, I was intrigued by various aspects of their lives, such as the experiences of Dom men working at cremation grounds and the educational opportunities for Dom children. I also wanted to explore the autonomy and aspirations of Dom women. I also feel that the Doms often go unnoticed because those from dominant castes prefer not to engage with their lives beyond their role in cremation rites. This indifference arises from a privileged perspective that allows people to overlook the challenges faced by the Dom community. This curiosity fueled an eight-year research journey that culminated in the completion of my book in early 2023.

Q. In your book, you recount the story of Dolly Chaudhary, who is prohibited from witnessing her husband’s cremation due to the community’s belief that women are too frail for such sights. Being a woman yourself, how were you welcomed when engaging with this community?

If you visit the Manikarnika Ghat, you’ll find plenty of men working as wood vendors, cremators, vendors selling items required for funerals and families standing beside their deceased members. In such an environment, a woman carrying a dictaphone in one hand and a camera hanging from her neck naturally attracts attention. Initially, I felt as though all eyes were constantly on me, which was quite discomforting, especially when trying to concentrate on my work. It took me some time to adjust to this, but eventually, I did. When I attempted to interview the Dom men working at the ghat, they were initially hesitant to engage with me. Firstly, I was an outsider—unknown to them. Secondly, being a woman, they were not accustomed to a female approaching them and requesting an interview. It required persistent effort to gain their trust and eventually break down their initial reservations. Through repeated visits to Manikarnika Ghat, they gradually began to trust me.

Q. Could you recount an anecdote from your interactions with the women of the Dom community?

I recall coming across a woman cooking in a cramped home without electricity during the scorching summer months. When I proposed stepping outside for some fresh air once she finished her chores, she confided that she didn’t have her husband’s ‘permission’ to do so. Furthermore, married Dom women must veil their faces with a ‘chaddar’ when leaving their neighbourhood, a practice they find confining but are obliged to follow. Additionally, they must always be accompanied by their husbands or a male relative when venturing beyond their community.

Q. Based on your book, it’s evident that the Dom community continues to endure poverty, with a few individuals earning as little as 250 rupees per cremation. Can you describe what you observed regarding their living conditions?

The families residing there lack access to basic human amenities. A few households, with as many as ten members, reside in severely congested accommodations. They face water scarcity, electricity problems and pervasive poverty. Survival becomes a day-to-day struggle where education takes a backseat to earning a livelihood. Consequently, many parents withdraw their children from schools and send them to work at the cremation ground to help support the family.

Q. Despite their impoverished circumstances, the Dom community sustains themselves by working as corpse burners. Would you say they take pride in their profession?

Numerous Doms deeply hold the belief that they are carrying out a divine mandate. They see themselves as the sole bestowers of moksha (salvation) upon the departed souls, believing that the Almighty has bestowed upon them the exclusive privilege of sacred fire. Consequently, there exists a sense of pride associated with their work, serving as a means for them to validate their presence within a society that often ostracises, distances, and regards them as untouchable. The capacity to grant moksha represents their religious capital, offering them a sense of worth and acknowledgment in their community.