Tej Pratap forces constable to dance on Holi, evokes fresh political controversy

However, he crossed the line when he instructed a police constable in uniform to dance to a song, warning that he would be suspended if he refused.

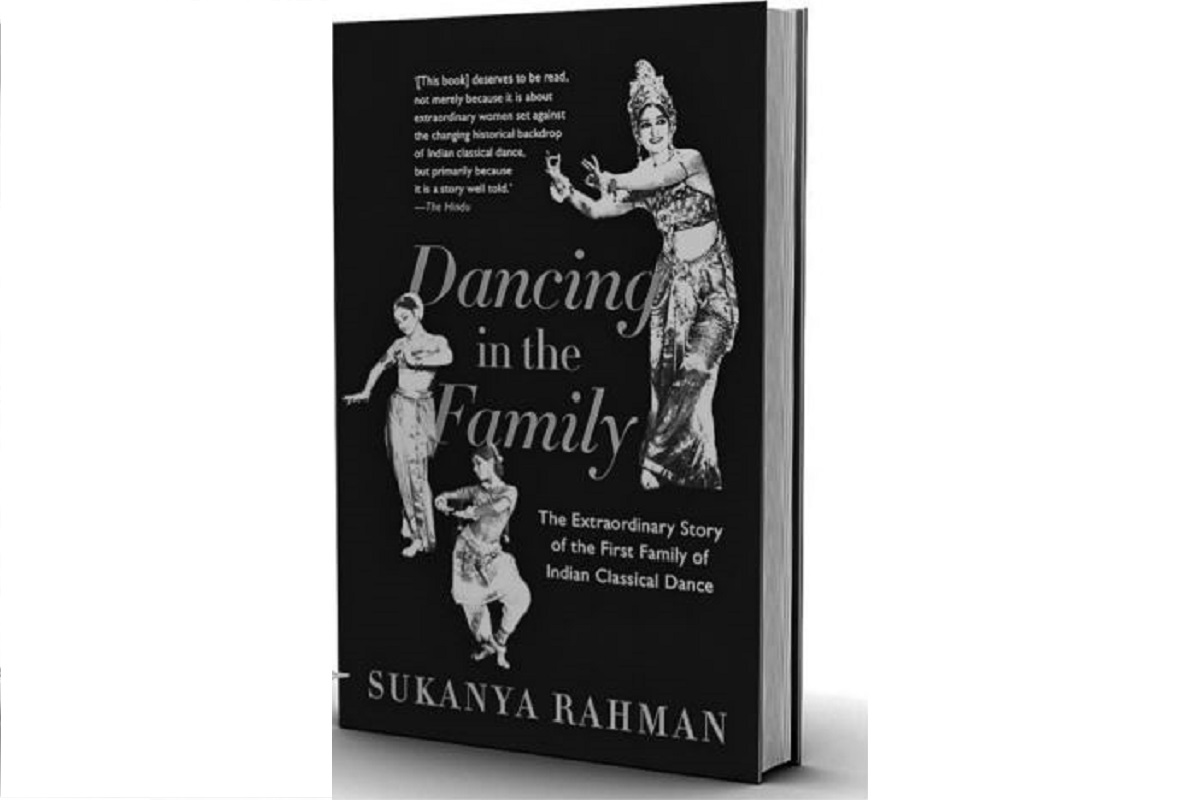

The book is a chronicle of the lives of three generations of unconventional women. Rahman leads the reader on, chapter by chapter, in an easy flowing informal manner stringing the whole story in one common thread.

Tapati Chowdurie | New Delhi | July 1, 2019 3:20 pm

(Photo: Statesman News Service)

‘Dancing in the family’, by Sukanya Rahman, is the extraordinary journey of three generations of unconventional women for who dance is a passion. Each took up the baton from her predecessor and continued the relay race in their own unique way. The indomitable spirit of the trio has made a difference in the Indian dance scenario. The title is indicative.

As early as 1926 Esther Luella Sherman of Minneapolis, having successfully transformed herself entirely and “became the music that drew her to India” and called herself Ragini Devi, wore saris, put vermillion on her forehead, darkened her skin with “Indian mud”, declared to an American reporter, that she was a upper-caste Kashmiri Brahmin girl.

Advertisement

It is her ‘Indian-ness’ and ‘Hindu-ness’ that set her apart. She gave solo performances of her genre of Indian dance in the United States. All because of her twin belief that only an Indian could reveal the spiritual beauty of the art and that dance and music are acts of worship, which is one of the finest phases of Hindu life that must be made known to the world.

Advertisement

Besides dance, the narrative includes details about their personal, social and stage lives along with glimpses of the freedom struggle of India and the communal riots unleashed in 1946. To know the details of her grandmother’s involvement with Harindranath Chattopadhayay, Sukanya questioned Kamaladevi Chattopadhayay, his wife, but both women were tight-lipped on the subject.

The book adds to our knowledge of Indian classical dance during the 1930s during its revival. Both, Ragini Devi and Indrani Rahman her daughter, were at the heart of its revival in the 20th century. Esther Luella Sherman’s passage to India was a racy tale of high romance after desertion and the subsequent delivery of a child not looked forward to, for fear of having to give up a career of dance, only to change her mind when prophesied by a gypsy that her newborn daughter would be more renowned than her and then giving birth in the ship on the way to India, was a fitting subject for a novel.

A life of ease at Bangalore, learning ‘abhinaya’ from Mylapore Gouri Amma of Kapaliswara Temple, subsequent tours all over India in the early thirties on a shoe-string budget was phenomenal. In Kerala Ragini fell in love with Kathakali and became the first foreigner to learn it in Kerala Kalamandalam. It is here where she met young and handsome Gopinath, the Kathakali dancer from Travancore, who agreed to be her dance partner in her tours. Thanks to Ragini Devi, history was created.

Kathakali came out of Kerala to the world stage. Gopinath gave credit to Ragini Devi for the success of their programmes and her pioneering work in making Kathakali known nationally and internationally. In 1934 Ragini Devi and her troupe were invited to perform at Santiniketan. The Nobel Laureate was happily witnessing ‘Sita Harana’ in full Kathakali costume, when the shrieks of the four-year-old Indrani made heads turn, soon to be pacified by Rabindranath Tagore.

The larger than life sight of Ravana Gopinath trying to abduct Sita had traumatised the little child. This novel dance-drama was highly appreciated by the literary genius and the audience. Tagore wrote about this dramatic experience in a letter of thanks to Ragini Devi. The fiasco of the troupe’s European tour ending in Ragini and Indrani’s subsequent escape by boat from Paris to London is hair-raising. Ragini had lost her citizenship by dint of her marriage to an Indian. To get it back there was high drama.

Ragini, by all accounts, was a dance superstar. After her death, Sukanya had retrieved from her collection a letter to one Mrs. Bradley written in February 1931, from Bangalore, with vivid details of her journey to India, about a broken love affair, birth of Indrani – her mother. Sukanya saw the ‘bravura’ of a woman who broke all obstacles to realize her passion for dance. Ragini’s reviews, articles and programmes are to be found in the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Centre. Among the books she wrote on dance were Nrityanjali and Dance Dialects of India. Indrani, her daughter was free-spirited, living out of a suitcase, soon realised that the only way to get her mother’s attention was to excel in dance.

At the age of 14 she married Habib Rahman, a 29-year-old architect – against the wishes of her mother and newly found father – initially introduced to her as ‘uncle Ram’ by Ragini, finally forced to confess that Harindranath Chattopadhyay with whom she had eloped, was not her father. Habib Rahman, a Bengali, was chosen to be the God of spring in Ragini’s new ballet. The day in 1946, prior to the Partition of India, when the newly married couple arrived in Calcutta to be with Rahman’s family in Panchnumber, Park Circus, they were confronted with the Hindu-Muslim riots. Sukanya gives details of this man-made human tragedy.

Details of Indrani’s lessons in Kathak under Guru Sukhdev Maharaj, the father of Sitara Devi and uncle of Gopi Krishna in Lower Circular Road in Calcutta and her Bharatanatyam Guru Chockalingam Pillai in Egmore, Madras, as well as the Bharatanatyam maestros from Mellatur and Odissi lessons from Guru Debaprasad Das from Odisha are chronicled with revealing details. Sukanya learnt from her father about Indrani being the first to win the Miss India title in 1952, which Indrani would rather forget. She wanted to be remembered as a dancer.

More than what she gathered from her mother’s interviews on print and tape, Indrani’s stories were brought alive at unguarded moments in her conversations. In the preface of her book, Sukanya talks about her admiration of her mother’s dance on Nataraja, who danced in Chidambaram. She was always mesmerized with the ‘sollukettu swaras’ of the cosmic dancer, balancing both creation and destruction.

In “Artist in school programme” in her son’s school in Maine, Sukanya’s embarrassed son asked her never to come to his school in that costume dripping with snow. Then again when she was requested by the same son to perform at the Chocolate Church Arts Centre, at Maine, for his college, thunderous applause at the end of it, with Habib stepping on stage and presenting her a bouquet was indeed the most joyful moment of her life.

Besides being an Indian classical dancer Sukanya has learnt Modern Dance at The Martha Graham School in New York. She is also a visual artist, who studied painting at the College of Art, New Delhi and Ecole Nationale Superieure Des Beaux-Arts in Paris on a French Government scholarship.

The book is a chronicle, which provides a good read. The writer holds a torch to the daring adventures undergone by the three in pursuance of that which was dear to them, in a lucid manner. She leads the reader on, chapter by chapter in an easy flowing informal manner stringing the whole story in one common thread, developing the ideas as they peep into her story, without forcing unconnected details.

The content of the book is so varied that to expect the conclusion to be a summary of what it is, is well nigh impossible. Rahman has ended the book logically with the funeral of her mother Indrani Rahman who died in 1999 of a massive heart attack. At her funeral, drama giant and art collector Ebrahim Alkzi quoted Dylan Thomas and spoke of her “going gently into that good night” Though she had given up performing in 1989, she continued teaching her students at Juiliard and presented promising young solo Kathak, Odissi and Bharatanatyam artists at various venues.

Advertisement

However, he crossed the line when he instructed a police constable in uniform to dance to a song, warning that he would be suspended if he refused.

Speaking about their relationship in a recent interview, Abhinaya had shared, “I have a boyfriend. We are childhood friends, and our love has lasted for 15 years."

India’s soft power is not limited to a slew of well-made feature films across languages, or the treasure trove of the traditional arts, music and dance – but creativity infused into the big Hollywood movies that are being processed here in Namma Bengaluru and a few cities in neighbouring states.

Advertisement