Eight killed in new US airstrikes on Yemeni capital

At least eight people were killed in US airstrikes on Yemen's Houthi-held capital Sanaa, Houthi-run health authorities said in a statement.

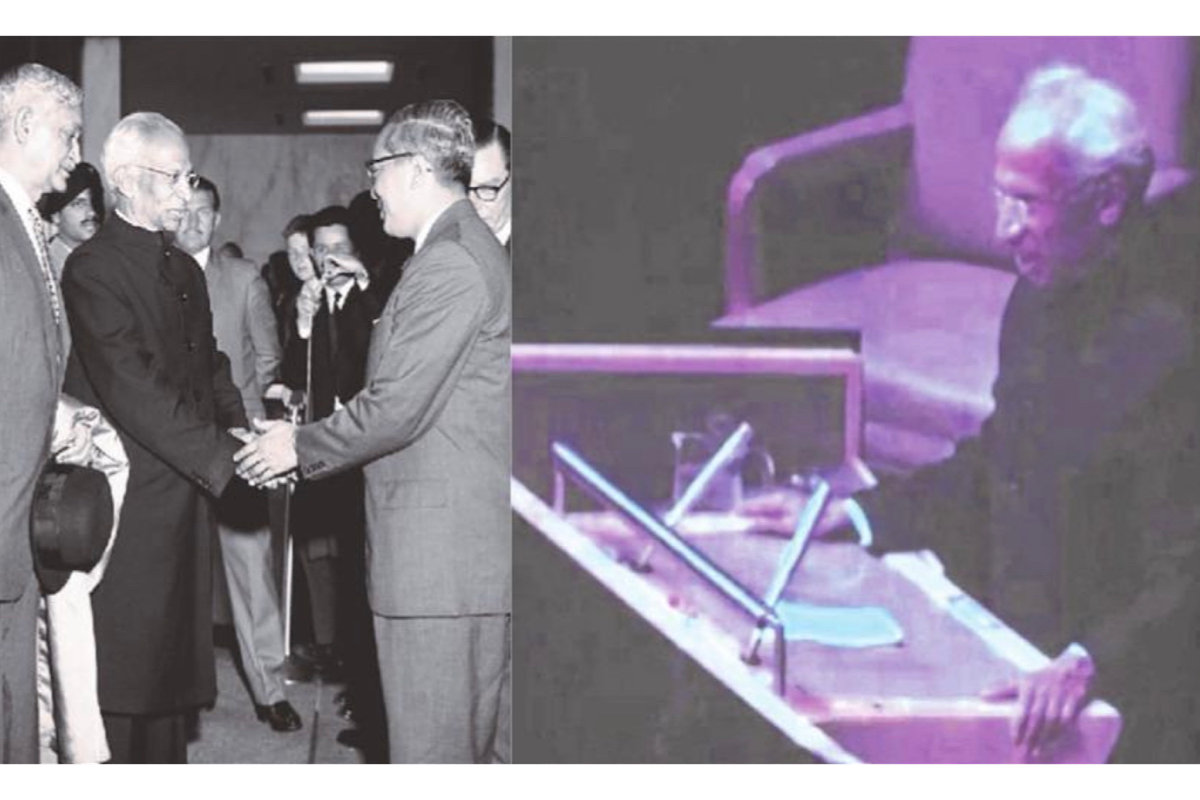

Representation image (Photo:SNS)

On 10 June 1963, when President Dr S Radhakrishnan delivered his speech at the United Nations General Assembly, the world community was recovering from the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

United States of America and Soviet Union, both nuclear powers, were in an eyeball-to- eyeball confrontation over missile and bomber bases in Cuba.

Advertisement

Through September and October 1962 global peace was at peril; it was a critical moment in the cold war, as the media reported. US President John F Kennedy made it clear that his country would not stop short of military action to end what he called a “clandestine, reckless and provocative threat to world peace.”

Advertisement

India, through those months of 1962, had faced a full-scale Chinese invasion of India which started on 20 October. Chinese troops moved down the western and eastern sectors in large numbers, with mortars and mountain artillery and attacked the heavily outnumbered Indian forces.

India had no choice but to defend itself with all its might. Prime Minister Nehru said, “no self-respecting nation would tolerate such outrageous aggression…we can never submit or surrender to aggression. That has not been our way.”

Dr S Radhakrishnan, during his address, took the opportunity to focus once again on global peace. He refrained from making any reference to the Chinese invasion of India and the traumas which the young Republic had to bear.

He said, with candour, “the most essential part of the work of the United Nations is to save the world from wars. What is it that we find actually? The piling up of armaments and nuclear tests. These things do not give us much hope.

We feel that if these armaments go on piling up and if these stockpiles increase, by accident, or by mistake, the world may burst into fragments. Even if that does not happen, when there are nuclear tests they are bound to injure not only present generations but also generations still unborn. We deliberately consign thousands and thousands of young children throughout the world to this kind of decadence, physical and mental.

That is what we are doing. Why is it that when we actually know what the results of these things are we are unable to prevent them? There is something radically wrong.”

The US visit of the Indian President had been hailed, and headlined, as ‘A Philosopher’s Journey’.

The phil osopher in him did not mince words when he reminded the august General Assembly, “we are the victims of the past; we do not wish to be the servants of the future.

We are the victims of the nationalist and militarist kind of society. Other nations were regarded as supreme, and for achieving the aims and political ambitions of those nations we

hitherto resorted to the use of force.

But we have come to a condition when the nation State has to be subordinated to the larger concept of world community. Unless we are able to do it, unless we give up the use of force, which is intolerable, detestable and wicked in the world where nuclear weapons have developed, it will not be possible for us to bring about peace in the world.”

Mahatma Gandhi’s influence, his firm belief in ahimsa or non-violence, was referred to by Dr Radhakrishnan as he questioned, “What we are trying to do? It is a change in the minds of men that has to be brought about. We are still believing in the nation-State and in the right to use force to have our own aims realized. These are the things which have us by the throat. Though we are members of the international community, though we call ourselves Members of the United Nations, our loyalties are to our own nation States; they are not to the world as a whole, not to humanity as a whole. We must break away from the past, we must get out of the rut in which we lived.

“Mahatma Gandhi once said: ‘I want my country to be free. I do not want a fallen and prostate India, I want an India which is free and enlightened. Such an India, if necessary, should be prepared to die so that humanity may live’.”

On nationalism, Dr Radhakrishnan held forth more as a historian-philosopher than ever before. He unequivocally stated, “Nationalism is not the highest concept.

The highest concept is world community. It is that kind of world community to which we have to attach ourselves. It is unfortunate that we are still the victims of concepts which are outmoded and which are outdated. We are living in a new world, and inanewworlda new type of man is necessary. Unless we are able to change our minds, to change our hearts, it will not be possible for us to survive in this world.

The challenge that is open to us is; is it to be survival or annihilation?”

Words like ‘annihilation’ ‘confrontation’ and ‘survival’ had been commonly used through 1962, probably most virulently after the end of World War II. Day after day media headlines were dramatic, bold, challenging and taunting.

In such a context, gripped by war-frenzy and hatred, Dr Radhakrishnan raised a series of questions in his speech, “It is easy for us to say that we wish to survive. But what are we do- ing to bring about that survival? Are we prepared to surrender a fraction of our national sovereignty for the sake of a world order? Are we prepared to submit our disputes and quarrels to arbitration, to negotiation and settlement by peaceful methods? Have we set up a machinery by which peaceful changes could easily be brought about in their world?”

These were not mere rhetorical questions but words of caution, guidelines for world peace coming from Dr Radhakrishnan.

“So long as we do not have it there is no use in merely talking. The concept of one world must be implemented in every action of every nation, if that on world is to become established. I have no doubt that the world will become one. As I stated, it is in the mind of events, it is the will of the universe, it is the purpose of Providence. We are being led from State to State to the concept of one family on earth. If we are able to achieve it, we shall do so by handling our own minds and hearts.”

His closing words continue to ring true today as we pay our homage to the philosopher- statesman every year during his anniversary in September. He said, “Our task today is to deal with the souls of men. It is there that the changes have to be brought about. Before outer organizations are established, inward changes have to take place. An outer crisis is a reflection of an inner chaos inside the minds and hearts of men. If that is not removed, we cannot bring about a more satisfactory world order.”

Dr Radhakrishnan had words of praise for UN Secretary General U Thant, a teacher and writer-scholar like him, from the neighbouring land of Burma.

U Thant was chosen to head the world body when Secretary General Dag Hammarkjold was killed in an air crash in September 1961.

Both U Thant and Dr Radhakrishnan knew that the United Nations Organization had come to symbolize the hopes and aspirations of the peoples of the world for a central authority which could eventually control the activities of all nations.

“Science and technology have brought the world together and made of it a single body. Economic systems are becoming interdependent, intellectual ideas are circulating all over the world, and what is necessary is to give a soul of this organization which is shaping itself before our eyes. The United Nations hopes to give that soul or that conscience to the World community which is emerging,” said Dr Radhakrishnan, bringing soul power onto the global centrestage.

When he underscored the importance of the United Nations being the conscience of the world, he was making a clarion call to safeguard the future. Our future.

(The writer, a researcher-writer on history and heritage issues, is former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)

Advertisement

At least eight people were killed in US airstrikes on Yemen's Houthi-held capital Sanaa, Houthi-run health authorities said in a statement.

Chaotic as it seems, Donald Trump’s tariff war and subsequent walk-backs are a deadly serious attempt by his team to address what they perceive as the core issues of the dollar-dominated global monetary system.

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Governor Sanjay Malhotra has exhorted the US industry to invest in India, stressing that the country continues to be the fastest-growing major economy, supported by policy consistency and certainty.

Advertisement