Election Farce

Four years after seizing power in a coup, Myanmar’s military rulers continue their desperate yet failing bid to tighten their grip, this time by extending emergency rule under the pretext of preparing for elections.

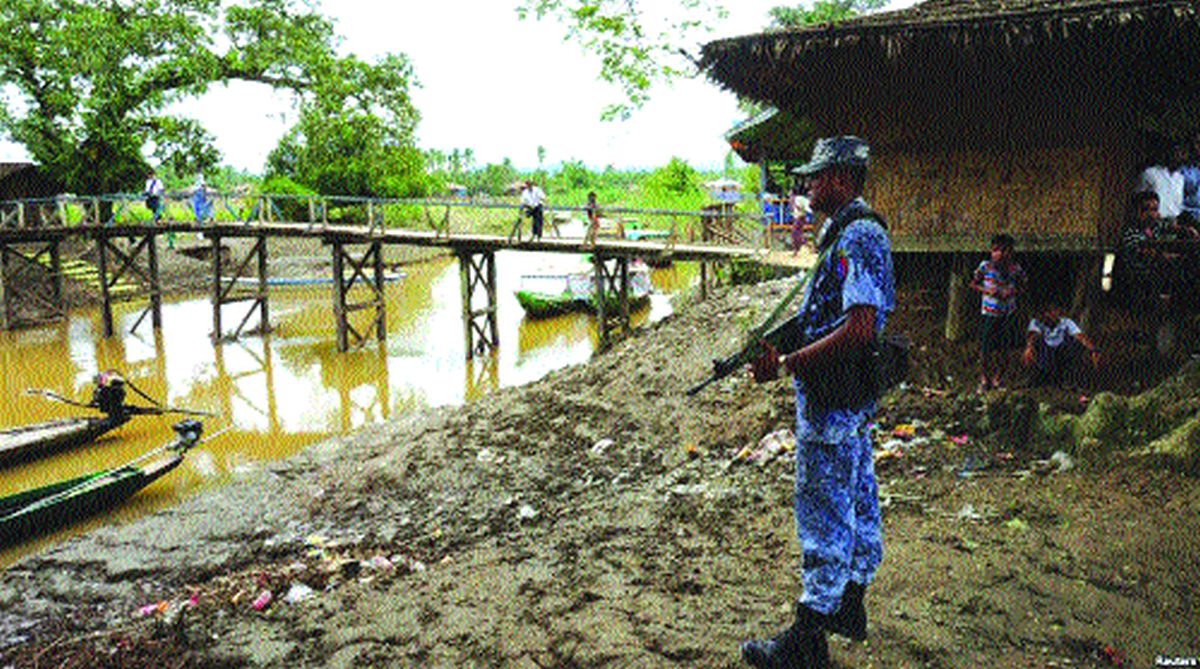

While the media spotlight on Rohingyas has primarily focused on religious persecution and ethnic cleansing, the strategic importance of Rakhine State of Myanmar needs to be articulated.

Rakhine State, where the Rohingyas have lived predominantly since time immemorial, is considered resourceful, but politically fragile. As we know, military operations ignited an ethnic conflict that resulted in the displacement of the Rohingyas from their villages in Rakhine State.

Advertisement

Accordingly, state-sponsored violence as sporadic episodes of brutal oppression of the Rohingyas in Rakhine province is believed to have evicted approximately 700,000 Rohingyas who have fled across the border into neighbouring Bangladesh since August 2017.

Advertisement

Why did the Myanmar government target the Rohingyas? What were the driving forces underlying the multiple episodes of eviction? In order to respond to these questions, we have to understand how “land grabbing” works. More specifically, this concept evokes images of the coercive mechanisms of state agencies, multi-national corporate stakeholders and elite actors used to evict smallholders or marginalised communities.

The violence instigated by the regime of the civilian-led administration was due to Rakhine’s geostrategic location and natural resources. Neighbouring countries have decided to invest in Rakhine province.

In response to these new trading networks and alliances, both China and India have become interested in building mega projects despite being rivals. Both countries proposed a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Rakhine State. China preferred the city of Kyaukphyu while India chose Sittwe.

To entice foreign countries or investors in the SEZ, land grabbing has been taking place, leading to the eviction of small landholders who depend on subsistence livelihood. In order to boost economic growth in Myanmar, the forced displacement of Rohingyas seems to be planned – it is a mechanism to create trading networks with China and India.

Apart from economic reasons, Rakhine province occupies a rather critical position in Myanmar and has a strategic perspective for both China and India. In the past few decades, China has been investing significantly in Myanmar, as a sign of thriving China-Myanmar friendship, in order to have a sway on regional politics underpinning the expansion of trading networks.

From a strategic perspective, Myanmar is situated between South Asia and Southeast Asia. The coastal belts of Rakhine, moreover, are access points to the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal for China – an opportunity to strengthen trade networks and military ties with Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. It seems that China has implicit desires to strengthen defence ties with Myanmar by using the Bay of Bengal – and only the coastal belts of Rakhine State provide such opportunities.

On the other hand, India’s strategy is to not only strengthen regional economic cooperation as an emerging superpower in Asia, but also develop surveillance systems for the provinces of north-eastern India, namely Mizoram, Tripura, Manipur, Arunachal, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, and Sikkim.

These provinces are poorly connected to the Indian mainland and have experienced many separatist movements or insurgencies, as well as share borders with Bhutan, China, Myanmar and Bangladesh. Both countries, thus, consider Rakhine as the “geopolitical headquarters” in order to materialise various political aspirations and implement mercantile strategies in the future.

The eviction of Rohingyas from Rakhine province was a state-sponsored crime. To accomplish this mission, the civilian-led administration established fresh strategic relations with Delhi and Beijing; this new alliance aims to reinforce military support to the Myanmar government. Despite the horrendous situation in Rakhine State, China and India still stand beside Myanmar.

In addition to the role of these countries, Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s de facto leader, played an extremely dubious role, as she allowed for the continuation of socio-economic development programmes in Rakhine State.

Accordingly, the most densely populated areas inhabited by the Rohingyas were not merely cleared – a total of 362 villages were destroyed too, according to a report published by Human Rights Watch. Approximately 48 investment projects in the areas were also given the green light.

The forceful expulsion of the Rohingyas from their ancestral home reflects the concept of “primitive accumulation” – formulated by the philosopher Karl Marx – which reveals the process of proletarianisation: the conversion of communal property to private property, the transformation of human relationships and the suppression of the rights of the commoners accompanied by coercive mechanisms.

The process of primitive accumulation thus provides a lens through which we can understand the current process of land grabbing in Rakhine State – how vast swathes of farmland, the coastal belts, and oil and offshore gas reserves are being captured.

Of course, Myanmar can propose and endorse schemes of “economic corridor” to boost its economic growth, but the ongoing persecution of Rohingyas and the latter’s expulsion from Rakhine State is a classic example of land grabbing which is associated with political, economic and biophysical conditions.

The Daily Star/ANN.

Advertisement