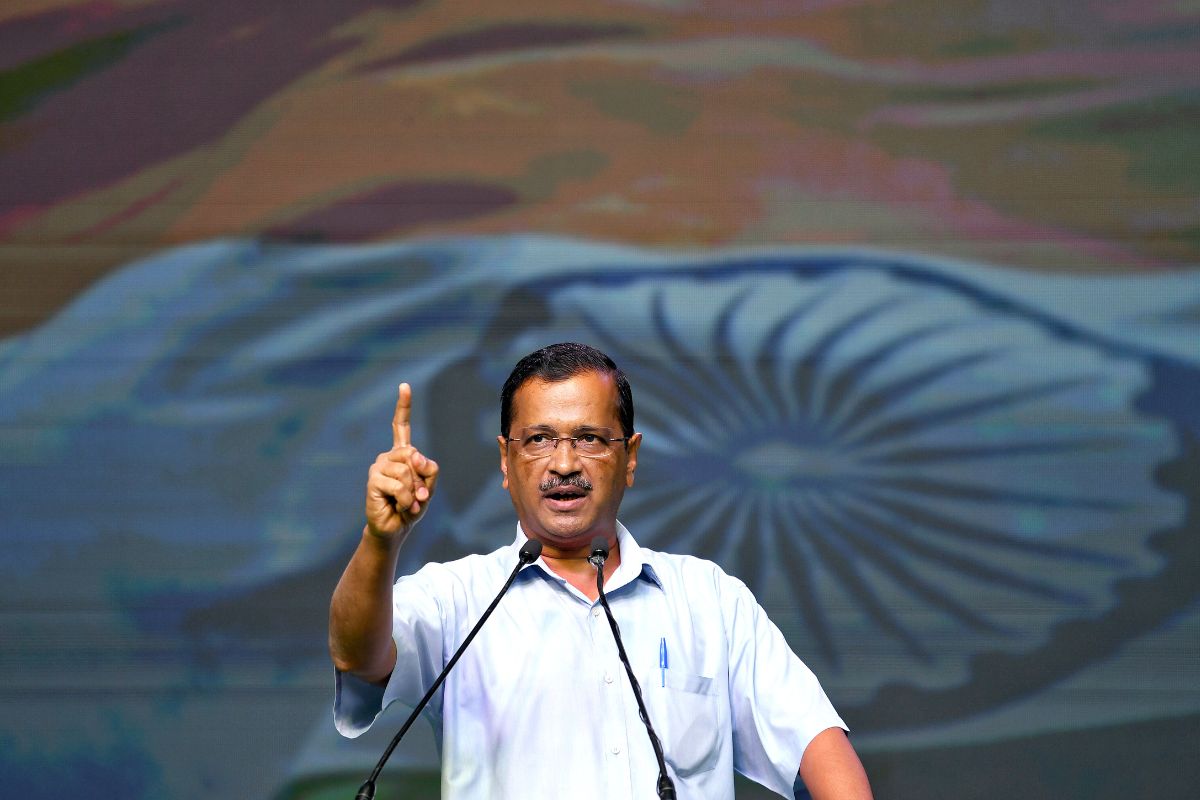

When faced with criticism, politicians are most adept at diverting attention to skirt the real issue, as seen once again in the ongoing debate on electoral freebies. The Aam Admi Party (AAP) led by Mr Arvind Kejriwal has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of electoral freebies in the country. It stormed into power in Punjab by promising a host of freebies which would drain the treasury by Rs 55000 crore, or almost 9 per cent of its GSDP ~ more than its own taxes of Rs 52000 crore. Punjab is almost bankrupt, staring at an impending financial implosion, but that didn’t prevent the AAP from making and implementing its reckless promises of freebies like free electricity, farm loan waiver, allowances to unemployed and adult women, etc. Now that the debate has occupied centre-stage at the prodding of the Supreme Court, Mr Kejriwal has deftly deflected this issue by calling into question the so-called freebies provided by the state on education and healthcare. In doing so, he has conveniently forgotten the role of the state as well as the distinction between public goods and freebies.

To be fair, all parties including the BJP had promised freebies also, though none could match the AAP in the game. When populism is reckoned and resorted to as the only means to power, no party can afford to be left behind. The short-sightedness, irresponsibility and unreason that underpin our political system conveniently underplay the fact that the freebies will have to be financed by borrowing whose fiscal consequences would severely limit the state’s development and growth. In a state with outstanding liabilities exceeding half its GSDP, this is a sure recipe for disaster. Mr Kejriwal knows this when his Chief Minister pleads with the Centre for a special package of Rs 1 lakh crore for Punjab, but that won’t deter him from extending the same freebies all over India if he could, damned be economic growth.

Advertisement

There are plenty of lessons in our neighbourhood to learn from, but politicians would not listen to anything that may diminish their electoral prospects, come what may. The practice of offering freebies for votes makes a mockery of the fact that in a mature democracy, a political party only owes good and corruption-free governance and nothing else to the voters. While delivering good governance is difficult, fulfilling promises on freebies is simple. It also undermines the fact that relief offered by freebies is very temporary and completely ignores the larger problem of scarcity, input costs and capacity, which need to be addressed over a longer time-period using the same resources. Of course, like populism, freebies are not easy to define; besides, perception of what constitutes a freebie may also change over time. Promise of a welfare state held out by the Constitution makes this tricky, and it is understandable that both the Supreme Court and the Election Commission have so far trodden this prickly arena rather cautiously.

In the Subramaniam Balaji vs Govt of Tamil Nadu case (2013), the Supreme Court had observed that “distribution of freebies of any kind undoubtedly influences all people. It shakes the root of free and fair elections to a large degree” and that “the promise of such freebies at government cost disturbs the level playing field and vitiates the electoral process”. Yet it had disagreed that it was a “corrupt practice” under the Representation of People’s Act and directed the Election Commission (EC) instead to frame appropriate guidelines. Since Article 324 of the Constitution gives the EC unfettered powers to superintend, direct and control the election process, it was for the EC to bite the bullet, but it took an equivocal stand: “There can be no bar on the state adopting welfare measures. But political parties must refrain from making promises that undermine the purity of the election process or aim to exert undue influence on the voters”, and that “there must be transparency with respect to the promises and how the parties aim to implement their promises.

The promises must also be credible. Wherever freebies are offered, parties must broadly state how they plan to gather the funds and finances to fulfil such promises.” The wording of the guidelines thus rather legitimised this practice, leaving the field wide open for political parties. The present direction of the Supreme Court to address the issue collectively by all stakeholders is the next logical step. The primary role of the state ~ especially in a democracy ~ is to let the market function freely and to intervene only when there is a market failure. A state is supposed to provide public goods that benefit the largest number of people in the largest possible ways. Examples of public goods are clean air and water, quality healthcare and education, safety and security of life and property, etc. Public goods are non-excludable and non-rivalrous, which means that the use of any public good by one does not exclude others from using the same and there is no supply constraint, unlike private goods (groceries or durables) which are excludable and rivalrous ~ they are priced and subject to the laws of demand and supply in the market. Indeed, excludability is an essential condition for generating revenue streams for the state on their sale or use.

Public good creates a positive impact on individuals and society ~ reason why it is the state’s duty to ensure that these are available to all citizens either free or at affordable cost. These cannot be confused with freebies. Free public education recognised by the Constitution as a fundamental right and made enforceable by the Right to Education Act, or free healthcare – though not explicitly recognised as a fundamental right in the Constitution but asserted as one by numerous Supreme Court judgments ~ cannot be called freebies by any stretch of imagination. To provide these is the primary responsibility of the state and it does so everywhere. Differentiating between private and public goods may pose challenge, their status may also change over time. For example, there are fundamental rights in our constitution which are not enforceable because there is no enabling act. Access to internet is one such, and if a political party promises a smartphone or a laptop to every student to facilitate this, this cannot perhaps be considered a freebie any longer. Similarly the Midday Meal Programme initiated by the Tamil Nadu Government way back in the 1960s was once considered a populist scheme, but given its positive impact in education, nobody considers it populist any longer. Important is to note that public goods are available to all sections of society.

But a loanwaiver to farmers or a subsidy to a specific section of voters, or free consumer durables so popular in Tamil Nadu cannot qualify as public good by any standards. The State also has a duty to provide relief to the disadvantaged and marginalised sections of society ~ but proper targeting is necessary for that to ensure that benefits reach only the deserving and not extended to those who can afford their costs. Since this is difficult to achieve, the easy way out is to make this universal and this is what makes the freebies unsustainable. They are not the same thing as providing relief to the needy and the vulnerable through carefully targeted government interventions like PDS. It is also to be noted that freebies inevitably distort the market and cause many other aberrations. Subsidy to fertiliser has contaminated the water bodies due to indiscriminate use, free electricity to farmers has depleted the groundwater tables because of over-drawal of water and loan waivers have completely perverted the repayment culture.

Doles don’t serve any economic purpose, they offer temporary relief the opportunity cost of which is the creation of capacity in economy which alone can create the wealth necessary to sustain subsidies and freebies. All advanced countries keep their subsidy expenditure well under control ~ mostly below just 1 per cent of their GDP. It is only in the developing economies where corruption is endemic and both productivity and efficiency are low that subsidies and freebies thrive. Politicians benefit from them, while rest of the economy slides down the slippery slope of wasting resources and slowing growth. There is also the morality aspect, because freebies militate against the culture of hard work in society that brings its own social and economic rewards. We need to learn from history. Like all great empires, both Greek and Roman Empires were built on the edifice of hard work; both rose to unprecedented exuberance and prosperity in their times before losing their vitality in the end.

To contain civil unrest, the Roman empire resorted to providing doles ~ free food to people and this “increased demand to live off the state” has been cited by Edward Gibbon, the author of the classic Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, as one of the major reasons for its fall. As regards Greece, what Edith Hamilton said in The Echo of Greece should serve as a warning to all of us: “In the end, more than freedom, they wanted security. They wanted a comfortable life, and they lost it all ~ security, comfort, and freedom. When the Athenians finally wanted not to give to society but for society to give to them, when the freedom they wished for most was freedom from responsibility, then Athens ceased to be free and was never free again.”