Kashmir Valley decides the fate of the J&K State Assembly by accounting for 46 of the 87 contestable seats. Jammu has 37 seats and the Ladakh region four, whereas another 24 are designated for the Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir region. This split has ensured that the Chief Minister of J&K has always been from the Kashmir Valley, with the exception of Ghulam Nabi Azad (2005- 08). He hails from Doda district of the Jammu region.

J&K’s wounded past and increasingly polarised politics have resulted in nine splits in the democratic functioning of state politics, including the promulgation of Governor’s Rule. However, J&K and its overall situation have emerged as the foremost metaphors in the 17th Lok Sabha elections in terms of security, sovereign decisiveness, nationalism. The fact that it contributes a mere six legislators to Parliament makes it relatively insignificant in the matter of forming a government at the Centre.

Advertisement

There are only three Lok Sabha seats from the Kashmir Valley. For the past 20 years, no elected Lok Sabha member from any of the three Valley-based constituencies has come from either of the two major national parties, and instead has rotated among the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) or the National Conference (NC). In essence, Kashmir dominates the national imagination and perceptions on national political parties and the electoral fate in the rest of the country.

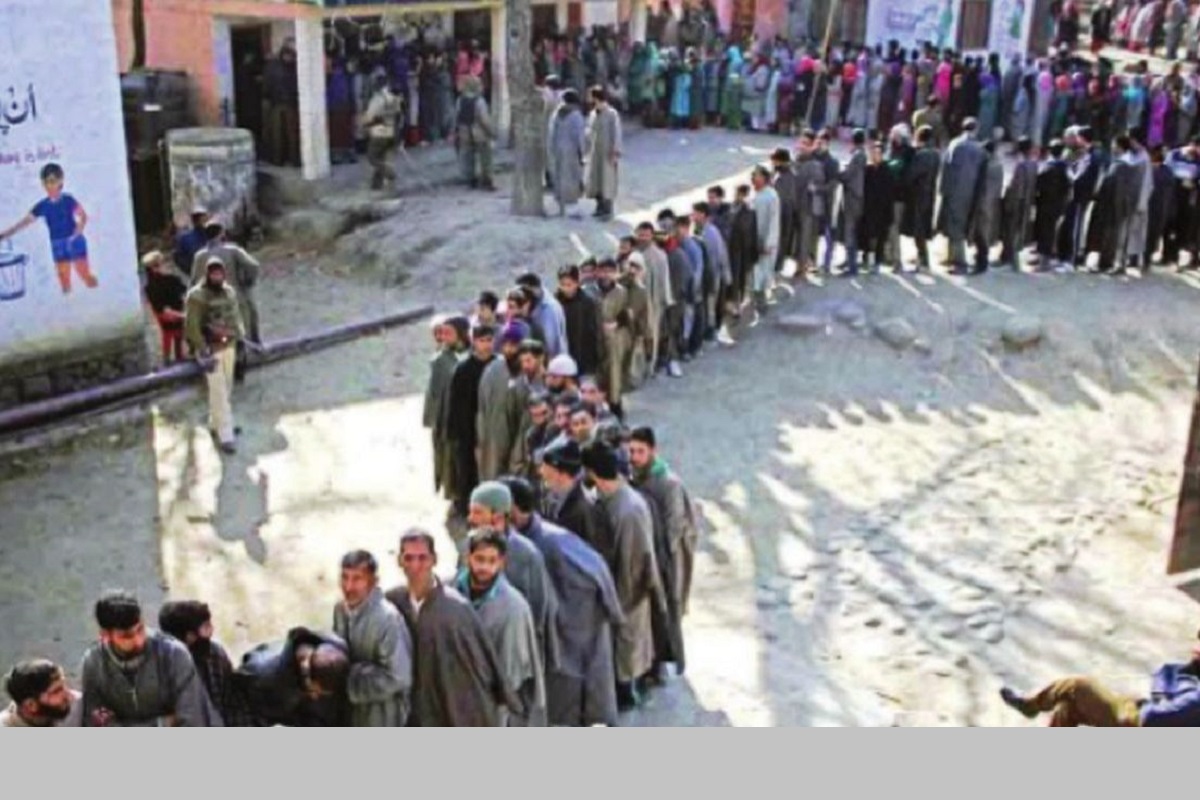

The crucial inclusion of the Kashmiri voice remains frozen under Governor’s Rule at the state level, and scarcely has an impact on the general election. The ground reality in Kashmir is reflected in the lowest voter turnout in the last two decades. In the restive district of Anantnag, which had a voting percentage of up to 40 per cent in the 2014 general election, the turnout this time was an abysmal 13 per cent. The staggered manner of the voting in the third, fourth and fifth phase for the three seats is symptomatic of the law and order situation. To that can be added the usual boycott call by the separatists and terror groups.

The frenzy and the fever pitch across the country has further reinforced the convenient stereotypes about Kashmir that no longer distinguish between the extreme separatists and the local political parties like the NC or PDP, who were earlier co-opted by the two major national parties. Irrespective of taints like ‘soft-separatists’, these regional parties afford the crucial link between local sensitivities and the populace with that of the Indian Constitution and its special provisions and guarantees afforded to J&K, given its unique history and terms of accession.

Like all political parties that have had irresponsible and disagreeable statements and actions attributed to their past, these local parties are no different . However, to push them into the dark alleys of ‘anti-nationalism’ is to snap the only link with political platforms of the Kashmiri ‘voice’, whilst wholly subscribing to the Indian sovereign and the Constitution. The instinctive retort of ‘Pakistan’ on local parties that could have a contrarian view to that of the ruling dispensation, comes with the automatic threat of banishment to ‘Pakistan’, essentially obliterating the hope for locals to participate in the Indian political process as opposed to falling prey to the regression of separatists and terror ideologies.

The recent security situation in the Valley is a matter of grave concern with the radicalisation of society. However tightening the security measures and infrastructure is not incompatible with trying to sustain and nurture the political process and impulse. The security imperatives and political process are not an ‘either-or’ option, but an ‘and’ axis in the successful closure of past insurgencies.

The electoral temptation of sounding politically muscular and ‘nationalistic’ across India has happened at the cost of further alienating a populace that has already and deliberately been misguided, armed and radicalised by the neighbouring country and its willing accomplices in the Valley. However, to ascribe all ‘voices’ emanating from the Valley to be ‘anti-national’ or ‘Pakistani’ is to do a great disservice to the ground situation that is showing dangerous signs of disenchantment and disconnect.

Instead of acting as an opportunity of societal inclusion, healing and emotional bonding, the electioneering soundbytes from the rest of the country are only deepening the divide. This narrative is starkly different from the more nuanced, mature and deliberately political approach that went hand-in-glove with the strict security imperatives to end the insurgency in Mizoram and Punjab. Today these states have recorded a healthy voter turnout of 63 per cent and 72 per cent respectively.

Both states are under Chief Ministers whose perceptions were different from that of the Centre at the time of insurgency. The emerging portents from Nagaland, where there has been a lull in militancy, can be attributed to genuine attempts at rapprochement, integration and understanding of local voices and issues, however uncomfortable it may have sounded at first. The future of the Kashmir Valley, the state of J&K and that of the Indian democratic traditions make it imperative to protect, harness and even mainstream legitimate matters of local concern.

Efforts must be made to engage with all local forces and political parties that do not have a separatist agenda or are willing to forego separatist agendas within the confines of the liberal contours of the Indian Constitution. An eye on the electoral implications in the rest of India has led to deliberately loaded statements during electioneering.

These are designed to infuriate local sensibilities in the wounded Valley, whilst reaping an electoral harvest across the balance of the 540 Lok Sabha seats out of the 543, at stake. These general elections have been a wasted opportunity for Kashmir and perhaps the more opportune time to thaw the freeze would be post the installation of the new government, when the electoral calculus is no longer relevant.

Today the lip service towards the Kashmiriyat- Jumhoriyat-Insaniyat formula is a far cry from the statesmanlike conduct of Atal Behari Vajpayee who could countenance the dual challenge of ‘inclusive-politics’ and security-decisiveness, without being undemocratic or authoritarian.

(The writer IS Lt Gen PVSM, AVSM (Retd), Former Lt Governor of Andaman & Nicobar Islands & Puducherry)