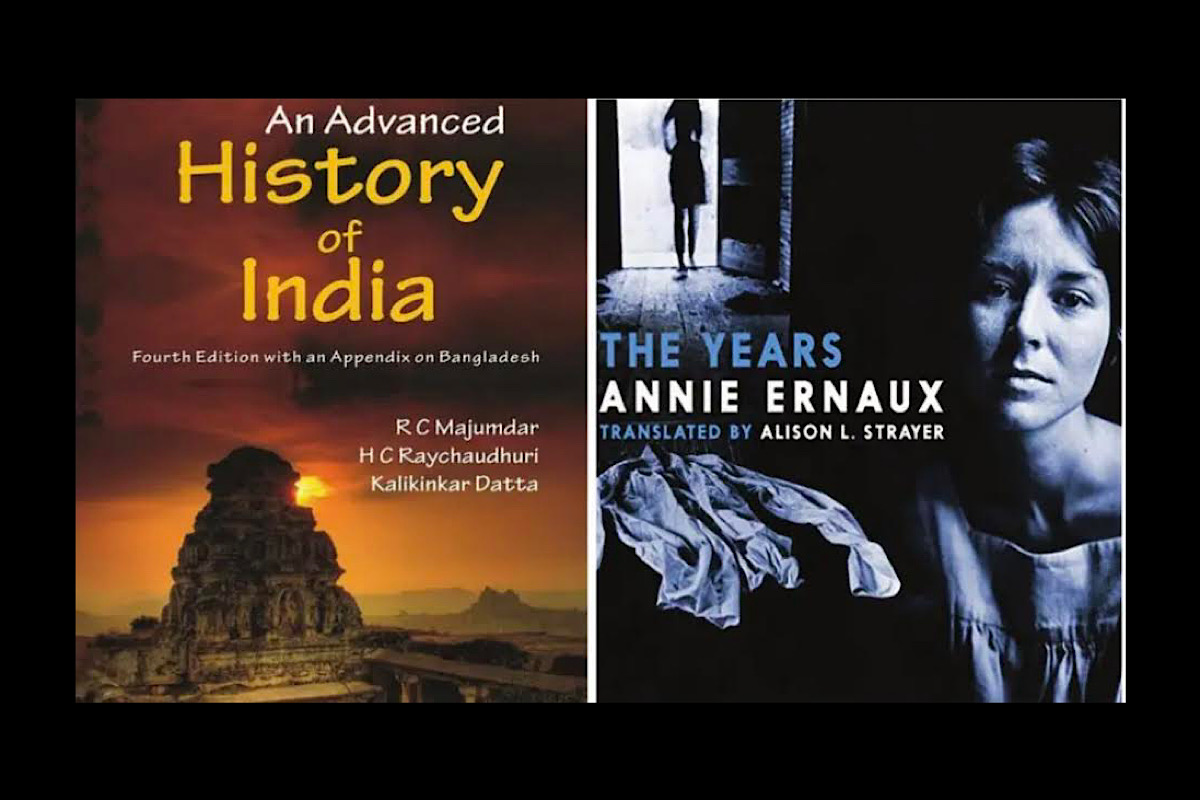

The images, real or imaginary, that follow us all the way to sleep ~ Annie Ernaux ( Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, 2022) in The Years. Once again, writing history is in national limelight. Some realignment of chapters in the NCERT textbooks has raised storms in the tea cups of most literate households. However, this is not a novel situation.

Interpretation of history has remained a contentious ground for academicians and politicians since India’s independence. In the 1950s, the legendary historian Dr R C Majumdar got involved in an imbroglio about writing an officially authorised history of the Indian Freedom Movement. Before and after this incident the veteran scholar repeatedly lamented the disinterest in history among his countrymen.

Advertisement

The situation has worsened over the years. Antiquarians, politicians, media professionals and even godmen have joined in to present their own version of historical events, especially regarding the golden ancient India and the volatile Muslim rule, to suit their present aspirations.

This is possibly an indicator of the post-truth age where a heady mixture of fantasy, entrenched beliefs and convenient portions of historical facts in the mind become more important than the facts themselves. What happened is overshadowed by what we wish to have happened. This is not really surprising in this country where for ages people have accepted myths and legends as history.

Modern historical research in India began vigorously with the establishment of the Asiatic Society in Kolkata in 1784. Since then no reliable historical records have been discovered for pre-Buddha times. Even for the history of post-Buddha times till the twelfth century we have to depend largely on inadequate Buddhist and Jain accounts and descriptions left by foreigners. The Sanskritic tradition of writing history is rather unsatisfactory.

The epics, poems, plays and philosophical treatises composed by the ancient Hindus contain numerous references to historical persons and incidents. But no proper work of history was penned by them except Rajtarangini by Kalhana in the mid-twelfth century.

The farce which passed for history amongst traditional Hindu literati, even in the early nineteenth century, is showcased in Mrittunjoy Bidyalankar’s Rajaboli (1808).

Composed when the British academic influence was not that deep, the Bengali work, based on old chronicles, is full of names and lists of kings who are supposed to have ruled from Delhi since pre-historic times. All these names were proved to be false and imaginary once Westernized methodical research on ancient Indian history started.

Actually, the ancient Indians did not take history or itihasa as an objective account of the past. Rather for them, itihasa meant presentation of some selected incidents from yore to highlight some virtues to be practiced in practical life. To stress these ideal qualities, the chosen events were presented in an imaginative or fanciful fashion.

Mahabharata, the greatest literary work of ancient India, claims to be an itihasa. But it is not a factual narrative of the later Vedic times according to modern ideas. It is a dramatized account of certain scenes of the history of the Kuru kingdom which highlighted specific qualities necessary to make life ideal. They include Gandhari’s virtuosity,

Vidura’s wisdom, Kunti’s patience, supreme glory of Vasudeva Krishna, the adherence to truth by the Pandavas and the evil deeds of the Kauravas. The historical value of this epic is so insignificant that we do not even know whether its chief political episode, the battle of Kurukshetra, ever took place.

Another group of Sanskrit works is the Puranas, at least 18 in number, which preserve traditional lores. Genuine historical rulers are mentioned there. But in the Puranas, the supernatural mixes with the natural and this drastically reduces their value as works of history.

A further proof of the ahistoricity of the ancient Indians is that the epics and the Puranas were not written at first but orally transmitted as poetry (kavya). Naturally as it went from one reciter to another, the original text got gradually distorted. Even when they were written down, they were preserved in hand-written manuscript form.

These could be easily tampered by later writers. The situation did not improve really even centuries later. A very important example of the local heroic poetry of the Rajputdominated early medieval age (700-1300 CE) is Prithviraj Raso by Chand Bardai based on life of Prithviraj Chauhan of Ajmer. This mentions some historical incidents and persons.

But this massive work contains a number of incredible and fanciful tales as well. Also, the court poets inserted some imaginary episodes glorifying the Maha Ranas of Mewar in the manuscripts of the Raso kept in that state. These are not found in the manuscripts of this poem elsewhere. This type of corruption seriously diluted the historicity of such works.

However, the ancient Indian authors were successful in attaining their objectives. Their epics, poems and chronicles were of considerable literary merit. These became very popular and people remembered them for generations. Naturally, persons of antiquity mentioned there became immortal in popular imagination.

Even today Rama, Ravana, Krishna, the Pandavas, Karna, Harshavardhana and Prithviraj Chauhan are vividly remembered, while luminaries like Mahapadma Nanda, Gautami Putra Satakarni and Pushyamitra Sanga, who were not subjects of literary works, are largely confined to the dry pages of text books.

Even Mahatma Gandhi praised this ahistorical way of remembering people and events. The problem started with the arrival of the British. Their scholars like James Mill ridiculed the Indians for their lack of precise history and dismissed the cherished yarns and legends as mere fantasies.

To restore their self-esteem before the colonial masters, the Indians, especially those coming out of Westernized schools and colleges, made strenuous attempts to discover the proper history of ancient India. The effort started with a meeting of the members of the Society for the Acquisition of General Knowledge, an academic body founded mostly by the students of the Hindu College of Kolkata, in 1838.

Gradually the contour of a reliable history of ancient India took shape owing to the researches of nationalist scholars like Rajendralal Mitra, Bhandarkar father and son, K P Jayasawal, Rakhaldas Banerjee, R K Mukherji, H C Raychaudhuri and young R C Majumdar.

Their torch was carried forward by liberal Marxists like D D Kosambi, Niharranjan Ray and D N Jha who opened up new vistas. These professional historians attached due importance to the traditional literary sources like the Vedas, the epics and the Puranas. But they were not ready to accept these without a question.

Rather they subjected the texts to critical enquiry and verified their contents in the light of new disciplines like archeology and philology. Naturally they found only a limited amount of proper history there.

They held the time of composition of the Rig Veda, the oldest piece of Sanskrit literature, to be around 1500 BC. Most importantly, according to them the Vedic Aryans migrated to India from Central Asia and South Russia.

(The writer is Assistant Professor in History, Vidyasagar College for Women, Kolkata and a former Faculty member, Presidency University)