Samsung seeks ways to cushion blow from US tariffs

Tech giant Samsung Electronics may need to overhaul its global production strategy as new US reciprocal tariffs could significantly affect its smartphone business, industry sources said on Sunday.

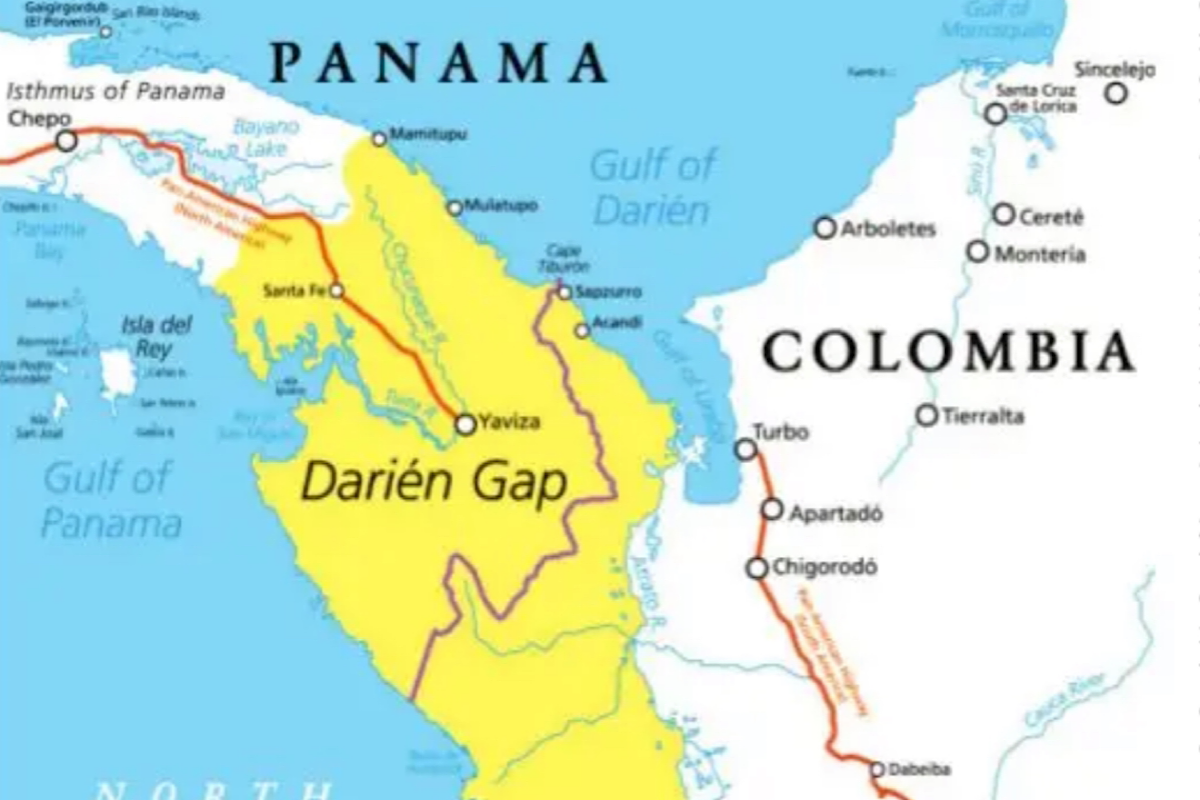

The Darien Gap is a stretch of densely forested jungle across northern Colombia and southern Panama. Roughly 60 miles (97 kilometres) across, the terrain is muddy, wet and unstable. No paved roads exist in the Darien Gap. Yet despite this, it has become a major route for global human migration.

Statesman News Service | New Delhi | March 20, 2024 7:18 am

Representation image

The Darien Gap is a stretch of densely forested jungle across northern Colombia and southern Panama. Roughly 60 miles (97 kilometres) across, the terrain is muddy, wet and unstable. No paved roads exist in the Darien Gap. Yet despite this, it has become a major route for global human migration. Depending on how much they can pay, people must walk anywhere from four to 10 days up and down mountains, over fast-flowing rivers and through mud, carrying everything they have—and often carrying children who are too young to walk—to make it through the pass.

Those who make it through then take buses through most of Central America and make their way north through Mexico to the US border zone. Cellphone service stops once people enter the dense forest; migrants rely on the paid “guides” and fellow migrants to make it through. In the decade prior to 2021, 10,000 people annually took this route on their way north to seek residence in the United States and Canada. Then, in 2021, the Panamanian government documented 133,000 crossings, a dramatic increase in human movement in such a volatile stretch of land.

Advertisement

In 2023, more than half a million people transited through this part of the Isthmus of Panama. The route, and really the entire trajectory that people take when they migrate from South America to North America, is controlled by criminal organisations that make millions, if not billions of dollars, annually in the human migration economy. It is impossible to cross this stretch of land without the help of a smuggler, or guide because the criminal organisations who control the territory demand payment for passage. Payment does not, however, assure safe passage.

Advertisement

Sometimes the very people paid to facilitate the journey extort migrants for more money. There are also reports of armed groups ambushing those in transit to seize their belongings and steal what money they may have stowed away and sewn into clothing seams. Extortion and kidnapping are common occurrences, and the medical aid charity Doctors Without Borders recently reported a surge in instances of mass sexual assault in which hundreds of people have been captured, assaulted and raped – often in front of family members. In December 2023, one person was sexually assaulted every 3½ hours while crossing, according to Doctors Without Borders.

The extreme nature of the swamp-like jungle also makes the journey dangerous. The paths can be very muddy, especially in the rainy season. In mountainous sections, it is often necessary to climb over steep rocks, or cling to a rope to not slip and fall off a cliff. The Missing Migrant Project reported 141 known deaths in the Darien Gap in 2023, which is likely a fraction of the actual number due to the challenges in reporting and recovering bodies. Many of the people I interviewed who had made the journey talked about seeing bodies along the path covered in mud, likely the result of slipping or falling to their deaths. Fellow migrants left markers close to the bodies, such as pieces of fabric tied to a tree, and took photos of the dead in the hopes that this evidence might someday help recover the bodies. The rivers are also dangerous.

Flash floods and rushing rapids mean that many people are swept away and drown in the muddy waters. Bruises, cuts, animal bites and fractures are common. The high humidity and heat each day, combined with a lack of clean drinking water, mean that many fall sick with symptoms of severe dehydration. Vector-borne, waterborne and fungal-related illnesses are also quite common. Violence, insecurity and instability in their home countries cause many people to move.

They may move to elsewhere in their region. But when the level of violence and insecurity is similar in that country, they keep moving to find a safer place to live. Options for legally allowed immigration are increasingly limited for those in low-income countries. For example, when governments implement travel visa restrictions for certain nationalities, it impacts the options available to the people of that country for movement. In 2021, with pressure from the United States, Mexico started requiring Venezuelans travelling to Mexico to carry travel visas.

This meant that Venezuelans hoping to seek asylum in the United States could no longer first fly to Mexico as a tourist and then present themselves at the border to a US Customs and Border Protection agent to express their fear of returning to their home country. Venezuelans had to find another route to move, and for many, that was and continues to be irregular transit through the Darien Gap without travel documents. In 2023, of the 520,085 people who moved through the region, Venezuelans counted for over half at 328,650. But the total also included 56,422 Haitians, 25,565 Chinese, 4,267 Afghans, 2,252 Nepali, 1,636 Cameroonians and 1,124 Angolans. Human migration in the Americas is a global phenomenon. It is also increasingly gender and age-diverse, as figures from the Panamanian government show. Adult men made up just over half of those moving through the Darien Gap in 2023, and adult women counted for 26 per cent of the population.

Children under 18 constituted 20 per cent of those crossing, with half of those children under the age of five. Parents may be carrying children for long stretches of the journey, or children may have to walk even though they are tired. The stress and fatigue add to the likelihood of injury along the way. The travel visa restrictions of many governments have only pushed more people to attempt this dangerous route. Governments have also been lukewarm to the presence of humanitarian groups who assist migrants in transit. On 7 March 2024, Doctors Without Borders reported that the Panamanian government would no longer permit the organisation to provide medical support to those in transit through the Darien Gap. This reduced access to health care will certainly mean a more dangerous passage.

In May 2022, countries across the Americas jointly announced the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection to improve regional coordination to manage migration. Through this, the US government implemented a series of new legal programmes to move to the US and application processing offices in South American and Central American countries that give people the opportunity to apply for US refugee resettlement, humanitarian parole and family reunification, and have the visas processed while waiting abroad. But these programmes are not available to people of all nationalities. And some of the programmes also require official documents like passports, a requirement that excludes many of those who make their way through the Darien Gap.

(The writer is a professor of Rhetoric, Politics & Culture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This article was published on www.theconversation.com)

Advertisement

Tech giant Samsung Electronics may need to overhaul its global production strategy as new US reciprocal tariffs could significantly affect its smartphone business, industry sources said on Sunday.

Canadian police on Sunday arrested a man who had barricaded himself inside the Parliament building after gaining 'unauthorised access' to the building's East Block.

An Indian national was stabbed to death in the Rockland area near Ottawa, Canada, prompting a swift response from local authorities. The Indian Embassy in Canada confirmed the incident early on Saturday morning, stating that a suspect has been taken into custody.

Advertisement