To Hegel do we owe the insight that the ultimate gain of an endeavour may well be different from its intended one. Jean Valjean, in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, attempts to rob Bishop Myriel of his sliver candlesticks. He ends up gaining something entirely different; and the rest of the story, spread over hundreds of pages, is an outworking of what this gain entails. The life of the erstwhile thief becomes a profound allegory, matched in world literature only by Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, of attaining a new life through repentance.

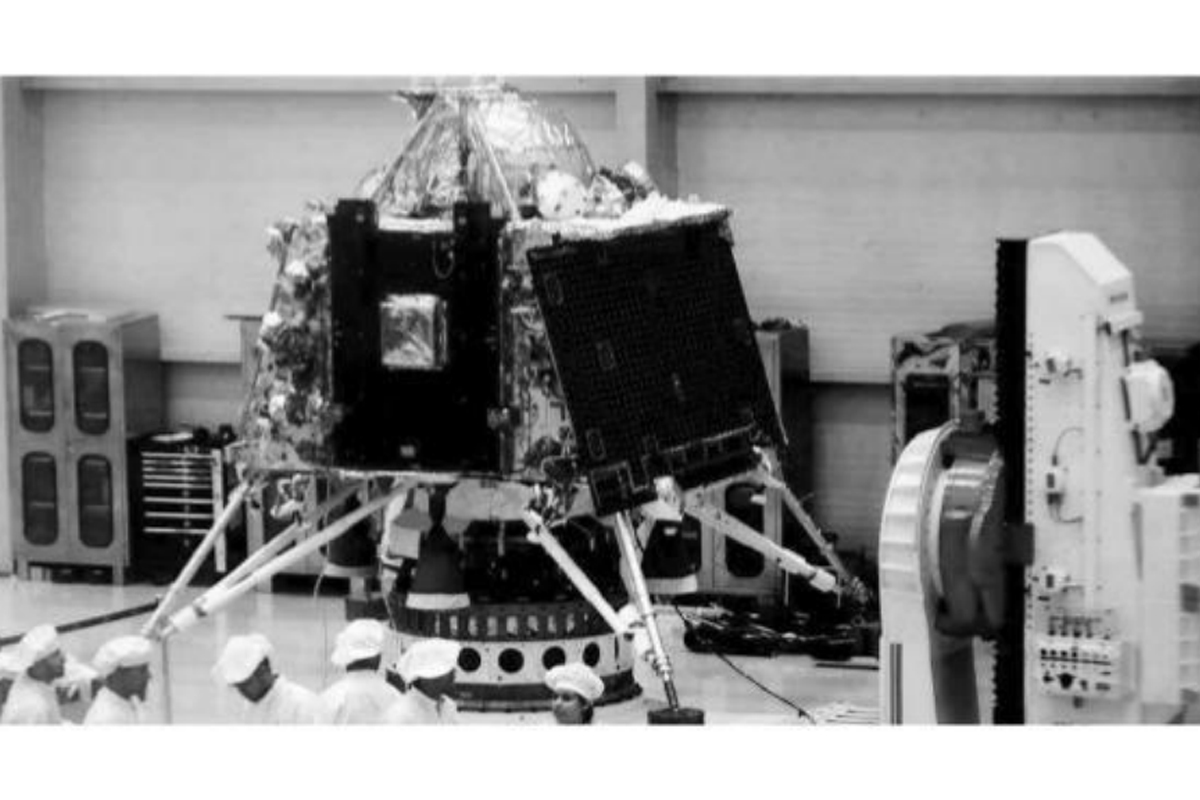

Chandrayaan-2 is something similar, something nearly as profound. How we understand an event is, at times, more significant than the event itself. As a matter of fact, the latter could determine the value of the former. Attempts were made, alas, to make Chandrayaan-2 a stunning national spectacle. This rendered us blind to the universal meaning of the event and its profoundly relevant message to the world at large. Here is the irony of the event: had Chandrayaan-2 ended up as planned, it would have been an event of great pride for India. But Chandrayaan-2, in ending up the way it has, has become an event of significance for humankind as a whole.

Advertisement

To see this aright, here is a principle we need to reckon. Every event in the external world occurs also within us, if we are inwardly alive; unlike a mirror which merely ‘reflects’ without reflecting upon. External events are not alien to us. This philosophical principle needs to be flagged for the reason that the culture that prevails today is one of external projections. This turns everything into a spectacle, which was done to Chandrayaan-2 as well. The details need not be recounted. As regards a ‘spectacle,’ its mechanism is more important than its meaning. Size and scale, not sense, is the pride. A spectacle is either an impressive success or a tragic failure. This explains the heartbreak that the partial failure of the mission occasioned.

It is overlooked that Chandrayaan-2 has become a global allegory on the human predicament. Its core pattern is the ‘loss of contact’ between ISRO and Vikram, the lander. This is not only a scientific setback but also an existential disaster. It is the root of all our woes. This pattern explains the gulf between our immense potential as a species, as people-groups and as individuals, and our achievements. We are eminently capable of landing on the Moon; that is to say, achieve difficult and challenging goals. But, for all our great enterprises and glorious abilities, there is a slip between the cup and the lip. We traverse tens and thousands of kilometers, but ‘lose contact’ and get lost at the door-step.

What frustrates good governance all over the world is the metaphoric ‘loss of contact between ISRO and the landing vehicle,’ between the centre and the periphery. Our prime temptation in this materialistic age is to adopt a mono-centric view of things, justifying it in the name of efficiency. So, the good democrats we are, we long for benign dictators. It is as though we can land ourselves on the Moon merely by making ISRO more and more powerful and pervasive. The lander, or the state, does not matter. It is, after all, a tiny satellite. This mindset undermines the vitality of a federal polity. Lip-service is paid to decentralisation, but the Centre becomes more and more unilateral and omnipotent. The fact is overlooked that the more this happens, the weaker becomes the link with Vikram and its mission. This explains why our track-record in implementation is abysmally poor. Brilliant schemes are conceived; but Vikram crash-lands, and nothing happens on the ground. In the end, there is little to show for the mega efforts undertaken.

The pattern works even more perversely in religion. Religion, if it is to merit that label at all, needs to be a dynamic link between ‘ISRO and Vikram’; ISRO symbolising the divine. Religion is like a circle, with a centre and a periphery. When the periphery becomes autonomous and loses the link with the centre, the circle is disrupted. The centre of religion is God. Religious establishments are like Vikrams. Both exist for a common purpose: the exploration of the lunar surface; analogically, the life of the people in religion. Religions, losing this contact, come to exist for themselves. Presumably there is some form of communication between the religious ISRO and the lunar orbiter, but there is no link with the lander and the ground. This tragic rupture is sought to be compensated with impressive religious spectacles; each year’s show outsmarting its predecessor in size and splurge. But what people need are spiritual experiences; nothing else can meet their needs. Such experiences issue from metaphysical ‘connectivity’. Religion is a means of staying connected to the divine for the good of the world; it has no other use or justification. Everything else is a farce and a deception.

Chandrayaan-2 mirrors what we have come to be. Why are we obsessed with the distant, the outlandish, the extra-terrestrial when we do not even know our next-door neighbour? Our fondness for speed and distance ~ distance is to space what speed is to time ~ is symptomatic of our alienation from ourselves and our fellow human beings. To be human is to be responsive and reflective. Consider this. You see a child about to put her finger into an electric socket on the wall. As the event happens out there, it also happens within you. You have to be a living corpse, if what could happen to her is a matter of indifference to you. You cannot be a mere ‘spectator’ to life. Yet, that is precisely what we are being turned into.

Various shows of extraordinary immensity and intensity are dished out to us. From the heaven-kissing statue of Sardar Patel to surgical operations, to the daring Balakot strike to making the impossible possible as in the abrogation of Article 370, to bullet trains, to space odysseys, we eagerly lap up the heady broth of the spectacular, but never stop to reflect and wonder what all these add up to.

Chandrayaan-2 had already happened within us, so to speak. In our inner universe the link with the lander is lost. We are merely orbiting, our courses remote controlled. Even as we orbit the Moon ~ so close, yet so far ~ we know we shall never land where we need to. The show remains; the goal is lost. Jacques Elul, the French philosopher, has an appropriate expression for it ~ the grand betrayal of the west.

Read thus, Chandrayaan-2 is a profound gain. It can indeed be a ‘giant leap’ for mankind. The meaning it radiates may not be to the palate that our species has acquired, especially since the Enlightenment. But eternal verities remain; notwithstanding Icarian flights and outlandish delights. We may escape the stratosphere and frolic in the cosmos; but we shall never outgrow the human condition and its core needs. No other achievements can make up for our devastating losses in this respect.