Cutting Red Tape

Transformative technological innovations of the twenty-first century have changed the way business is done the world over.

Francophone West Africa has for several years been beset by an Islamist insurgency that nations such as Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have failed to repel, despite international assistance.

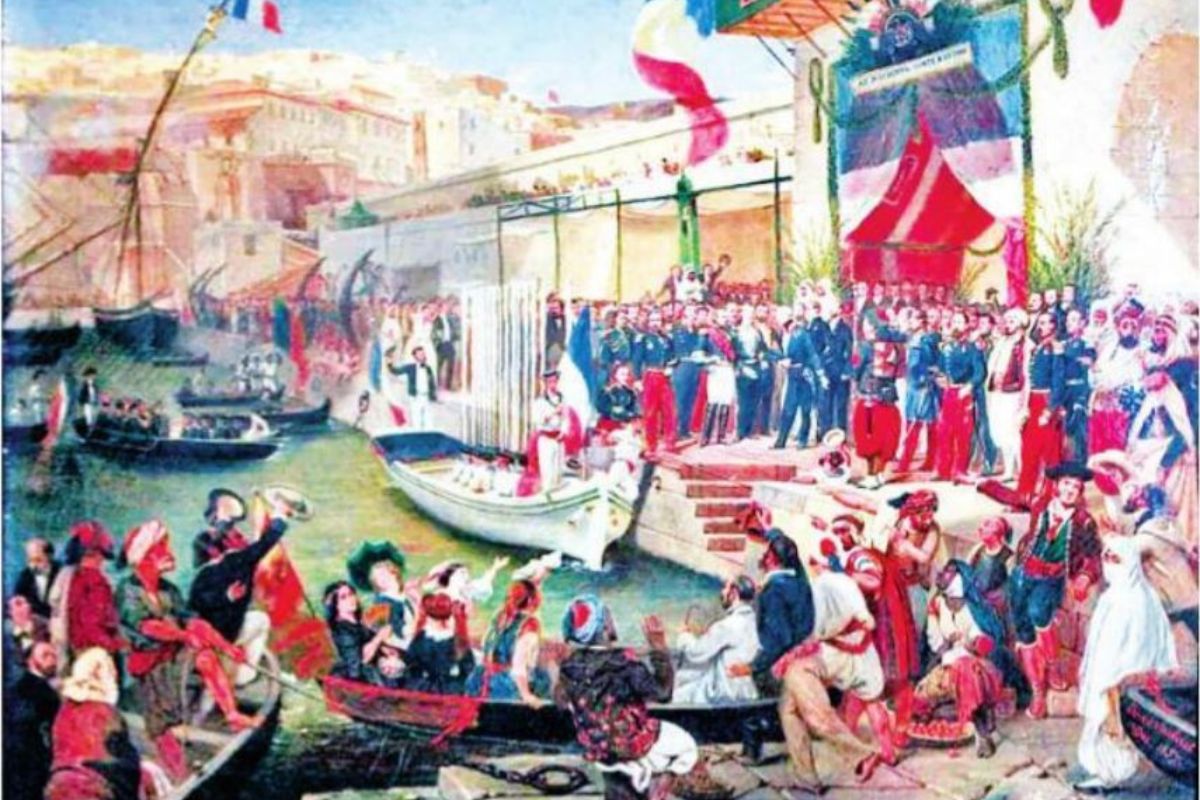

Photo: SNS

Francophone West Africa has for several years been beset by an Islamist insurgency that nations such as Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have failed to repel, despite international assistance. Much of that has come from France, the former colonial power. Mali, finding it ineffective, eventually switched to a different European power: Russia.

That does not entail official military deployment on the Western model — Russia supplies mercenaries ostensibly via the Wagner group. The Russian variant is a relative novelty, but European mercenaries have operated widely in ‘decolonised’ Africa for decades, with the semi-official approval of governments in France, Belgium and Britain. Less than 20 years ago, Sir Mark Thatcher, the former UK prime minister’s son, confessed to “unwittingly” funding a failed coup attempt in Equatorial Guinea. Simon Mann, the former SAS officer who led the plot, acknowledged that Mark’s mum not only approved of the plan but encouraged him to also turn his attention to Hugo Chávez in Venezuela.

Advertisement

Burkina Faso has this year witnessed two coups and the end of a key trial. The first coup, in January, involved the overthrow of an elected leader, Roch-Marc Christian Kaboré, by special forces commander PaulHenri Damiba, chiefly on account of the Kaboré administration’s incompetence in combating the forces of the deadly Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin.

Advertisement

The Damiba regime’s failure to make such a difference led to its ouster last month in a putsch led by Capt Ibrahim Traoré. Whether the second incarnation of the military regime can make much of a difference remains to be seen. It is notable, though, that in street marches celebrating both coups, a few of the participants waved Russian flags. The trial, meanwhile, related to the assassination of Thomas Sankara 35 years ago this week.

Regrettably, I was barely aware of Sankara during his brief but consequential empowerment. In his military uniform, he seemed like a typical military leader in a region prone to coups. But that was a gravely ignorant assessment. He ascended to power with a transformative politico-economic agenda. His four years in power (1983-87) included the renaming of what had hitherto been known as Upper Volta — an impoverished, landlocked nation with an underwhelming post-colonial experience.

More significantly, the Sankara administration implemented a series of health, education and land reforms that paid immediate dividends. In an echo of the early Cuban revolutionary experience, the level of literacy expanded from nearly negligible to almost universal. The world’s worst infant mortality rate substantially diminished. Sankara frequently cited women’s participation as a key component of his revolution, and Burkina Faso emerged as an African pioneer in laws against polygamy, forced marriage and genital mutilation.

He also reflected an environmental consciousness, and mass plantation campaigns helped to stave off desertification, while agricultural production flourished as irrigation projects were funded. Even though Burkina Faso was a poor country, Sankara resisted the idea of international aid, particularly IMF loans conditioned on neoliberal ‘reforms’ or ‘structural adjustment’.

He was keen on self-reliance and austerity under his administration, which mostly affected the elite — for instance, the government’s fleet of Mercedes limousines was sold off and replaced with the cheapest available car, the Renault 5. He rejected the idea of a presidential aircraft or first-class travel for ministers and often hitched a ride to international gatherings with other African leaders.

Sankara was vocally anti-imperialist in his overseas appearances and found common cause with Fidel Castro in Cuba, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and Mau-rice Bishop in Grenada. That made him unpopular with the neocolonialist powers — particularly France, which still keeps a paternalistic eye on its erstwhile empire. It almost certainly had a role in Sankara’s ouster as prime minister before he re-emerged as a coup leader, and French operatives were busy removing wiretap evidence on the day after he was assassinated.

The trial that ended in April pinned the blame for his murder at the age of 37 on his close associate Blaise Compaoré, who went on to rule Burkina Faso until 2014 — when he was airlifted by French forces to Ivory Coast amid a popular uprising after 27 years of iron-fisted rule. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in absentia.

Sankara, 35 years ago, joined the pantheon of African leaders, notably including the Congo’s Patrice Lumumba, whose dreams for the continent were deemed detrimental to Western interests. The fact that Russia and China have, in different ways, joined the scramble for Africa does not necessarily bode well. The jihadist nuisance is even more dire.

But as Sankara proclaimed, a week before he was killed, in a tribute to Che Guevara, to whom he is sometimes compared, “you cannot kill ideas. Ideas do not die”.

Advertisement