Path to a reset?

The re-election of Donald Trump as the President of the United States has once again thrown global geopolitics into flux.

Not every nation will share the same urgency, fear or even the plausible appetite for joining an alternative to the existing BRI that willy-nilly entails offending the Chinese, directly. But the conversations have already started. The alternative to BRI may not only be feasible, but completely unavoidable, unless the free world throws in the towel to the Chinese, completely

BHOPINDER SINGH | New Delhi | April 5, 2021 2:26 pm

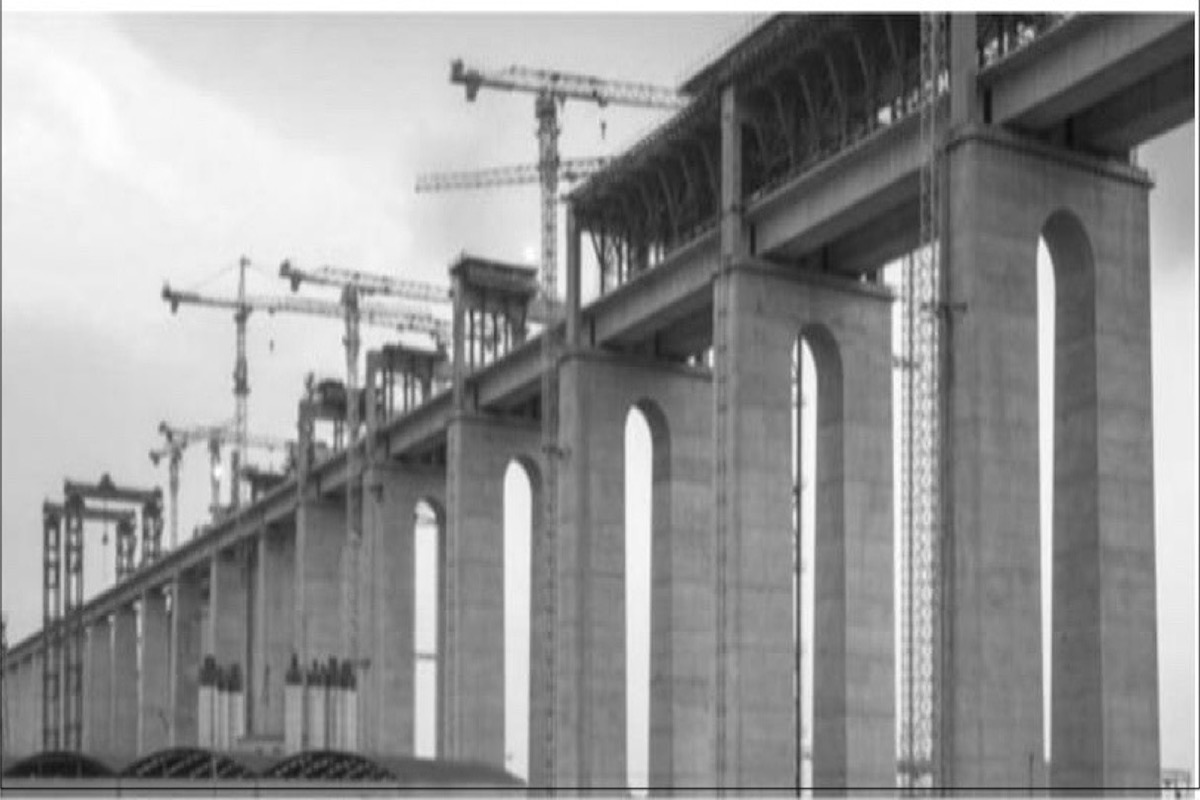

Xi Jinping’s centerpiece strategy of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was unveiled in 2013 as a ‘win-win’ initiative to 140 odd targeted countries across the globe. The infrastructural ‘network’ aimed to open access and create arterial routes to facilitate trade, investments and inter-connectivity with China as the epicenter of the initiative. Linking disparate, unfinished and un-started road/ maritime/rail projects under one rubric was unprecedented in its sheer temerity, scale and transformational ability.

The mandate was expanded into the digital, 5G networks, fiberoptic cable and space arenas to take the realm of possibilities beyond terrestrial asset creation. As the world was still coming out of the Great Recession of 2007- 09, battered major economies of the United States, European Union, Japan etc., were struggling to invest in ‘third world’ economies like earlier. Enter China, the oddity that was still flush with investable surplus and an insatiable appetite to invest, and a new ‘bloc’ of Sinosphere was on the horizon.

Advertisement

Much before the Covid pandemic saga played out, Beijing had shown its ability to turn a major global crisis into an invaluable opportunity to feed its own hegemonic instincts, with its BRI conceptualization. The Chinese juggernaut of the ‘military-industrial complex’ on the mainland was fueling the muscular outreach with its BRI imperatives planned over $1 trillion, to clearly desperate and option-less economies.

Advertisement

Beyond the obvious Chinese largesse, it was the supposed ‘ease of doing business’ with the Chinese that was making BRI irresistible. China’s no-stringsattached and no-questions-asked approach imposed no conditionalities on the host country to answer any awkward question on democratic freedoms, human rights, transparency etc., which was typically given to any potential aid from ‘free world’ donors and multilateral organisations.

Certain internationally isolated regimes like Pakistan, North Korea, Venezuela, Iran, Bolivia, Myanmar etc., were naturally and automatically drawn into the BRI dragnet. Mega projects like the $62 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) or the even larger $100 billion China- Myanmar Economic Corridors were borne out of the strategic BRI overlay. Almost eight years since its announcement, more than an estimated $800 billion has been ‘invested’ in the form of infrastructural projects or loans to over sixty countries, most of whom will inevitably struggle to repay the accompanying debt servicing requirements.

Consequentially, the Chinese global ‘hold’ has expanded beyond commercial angularities and it plays out strategically with the Sinosphere asserting itself collectively with the beholden countries dancing to the Chinese tune. The legs and arms of the fabled ‘Chinese Century’ have become daringly visible as one country after the other seemingly succumbed to the Dragon’s aggressive overtures, through a curious mixture of cheque-book diplomacy, bailouts, coercion and intimidatory territorial expansion.

Soon the cracks started showing as the recipient countries realised that the Chinese aid under the BRI was not so benign, after all. The growing Chinese footprint from the arid plains of Baluchistan to the urban dwellings of Yangon had started militating in the eyes of the wary locals. Sri Lanka sheepishly admitted its mistake in trading its ‘debt-trap’ for a 99-year Chinese lease of Hambantota Port, just as Maldives reneged on its initial dalliances with the Chinese, on the rebound with India.

Distant Zambians, Ethiopians and Papua New Guineans are having serious second thoughts at having entertained the Chinese option, and even China’s ‘all weather friendship’ with Pakistan did lead to murmurs in the Pakistani Senate of the CPEC as ‘another East India Company’! Even as Chinese territorial belligerence and expansionism in the South China Sea, Taiwan, Japan, Bhutan, Nepal and Indian borders was becoming all too visible, it was the Covid-19 pandemic that exposed the Chinese machinations and ‘playing down’ that subsequently wreaked havoc on the global economies. The Chinese are now suffering a serious reputational crisis and suddenly the BRI does not seem like manna from the heavens, after all.

Veteran China-baiter Joe Biden senses the opportunity to play a more fundamental game than indulging in binary ‘trade wars’ that can only bruise the American economy, even further. Biden has mooted an alternative multitrillion dollar infrastructural plan to rival China’s BRI. Like the BRI it envisages new age investments in domains like artificial intelligence, biotechnology, quantum computing etc., one that comes from the alternative ‘bloc’ of the democratic states!

Potentially the other parallel infrastructural ideations like the ‘Blue Dot Network’ to promote infrastructural development in the Indo-Pacific or the QUAD (US, India, Japan and Australia) formulation could be interconnected to give the BRI-alternative a headstart, a base and an ecosystem to build on. While more than 100 countries have already inked various sub-components of the Chinese BRI conceptualization – fears of erosion of sovereignty, debttraps and inequities have led to an all-time high fear of the Chinese ‘aid’ via the BRI, and therefore the search for a more equitable option, should it exist.

Beyond mustering the finances for a plausible alternative to BRI, the patience required in collating and ploughing the said ‘investments’ and overlooking certain sovereign governance issues (e.g. junta taking over in Myanmar has led to the US imposing punitive sanctions, whereas the Chinese dismissed it as an ‘internal affairs), will test any alternative to the existing BRI.

The US will have to deploy its more nuanced and holistic DIME (Diplomacy, Information, Military and Economic) approach, as opposed to invoking a purely militaristic approach in countering the BRI, as the China-wary world needs to be reassured of a dependable, committed and sustainable alternative that cuts across all the ‘need states’ of a sovereign nation. The post-Trump era has also left the Biden administration with the onerous task of repairing relationships with all its ostensible ‘allies’ to start with, before plunging into the task of pooling resources towards creating an alternative to the Chinese BRI.

Not every nation will share the same urgency, fear or even the plausible appetite for joining an alternative to the existing BRI that willy-nilly entails offending the Chinese, directly. But the conversations have already started, the timing could not be more appropriate to posit the idea and conjoin parallel streams of initiatives – the alternative to BRI may not only be feasible, but completely unavoidable, unless the ‘free world’ throws in the towel to the Chinese, completely.

Advertisement

The re-election of Donald Trump as the President of the United States has once again thrown global geopolitics into flux.

The Higher Buddhist Institute of the Tibetan Department in Beijing was initiated by the late 10th Panchen Lama and President of the Buddhist Association of China (BAC), Zhao Puchu, with the approval of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council, on September 1, 1987 in Xihuang Monastery in Beijing. The 10th Panchen Lama personally served as the first President, and Zhao Puchu, then President of the BAC, was the Senior Advisor.

US President Donald Trump's White House launched a Covid-19 website on Friday in which it blamed the origins of the coronavirus on a lab leak in China's Wuhan.

Advertisement