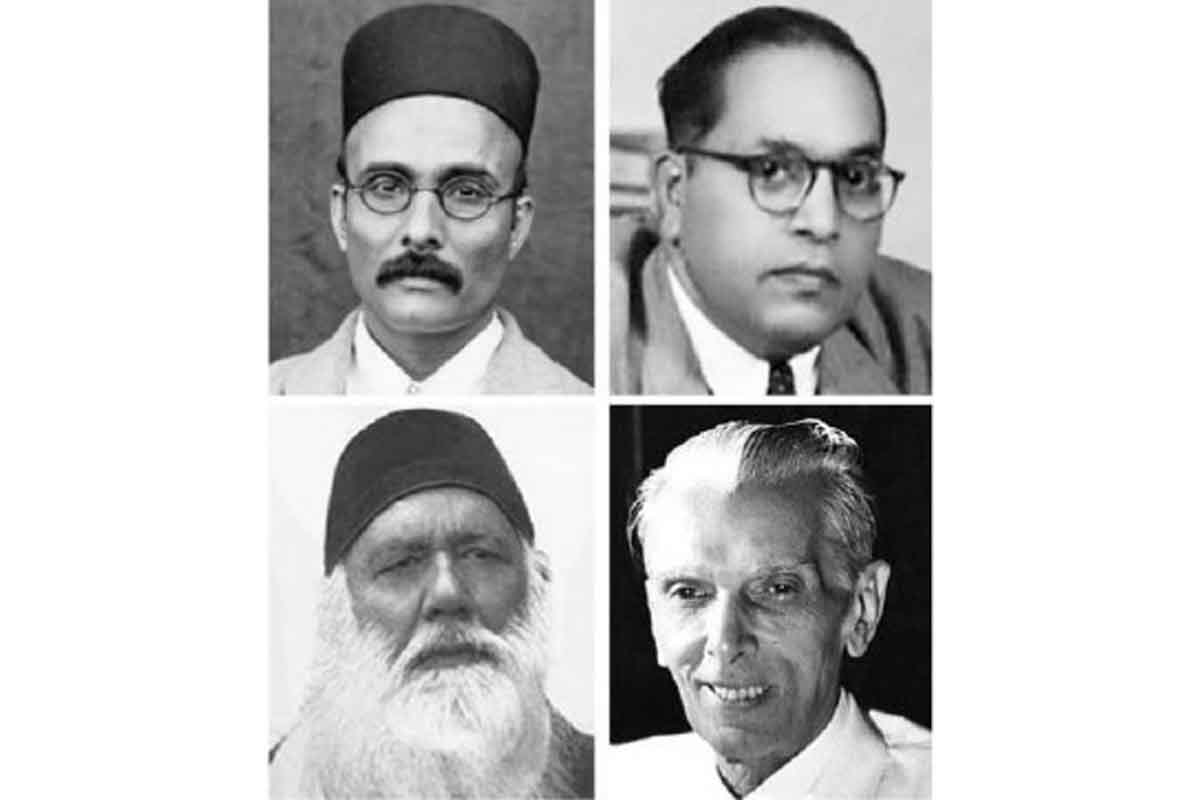

Veer Savarkar has of late been accused in the media of having introduced the two-nation theory. First, the author of the theory was Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan of Aligarh University. He first declared that Hindus and Muslims ought to belong to two different nations. This was in December 1887 at a public meeting in Lucknow. He again addressed the people on the subject of a separate nation at Meerut in March 1888. Syed Ameer Ali of Calcutta, the first Indian High Court judge, was the next sponsor of this two-nation theory.

Yet another public figure to do so was poet Allama Iqbal in 1930 at the Allahabad session of the Muslim League. He spoke of two Muslim nations within the Indian confederation; one in the north-west and the other in the east. Chaudhry Rehmat Ali, a scholar at the University of Cambridge, in 1933 innovated the word Pakistan. Then followed the redoubtable Mohammed Ali Jinnah who detailed the theory at length while sponsoring the Pakistan Resolution in March 1940 at the Lahore session of the League. Muslims are not a minority, Muslims are a nation according to any definition and they must have their homeland, their territory and their state.

Advertisement

The history of the last 1,200 years has failed to achieve unity, India has always been divided into Hindu India and Muslim India. The termination of British rule heralded a complete break-up. If Hindus and Muslims are brought together under a democratic system, it can only mean Hindu Raj. To very briefly quote Jinnah: Dr BR Ambedkar wrote a rejoinder with a volume called Thoughts on Pakistan the same year, and published in 1941.

A quotation would speak volumes for his patriotism and his vision ~ “He began to view Partition first from the angle of defence. The Indian army was predominantly Muslim in its composition. Russia or Afghanistan, the borders of both touch the borders of India’. Suppose the Afghans singly march on India, will these gatekeepers (army) stop the invaders or will they open the gates and let them in?

‘This is a question on which every Hindu must feel assured. Attention must be drawn to the stand taken by the Muslim League. That the Indian army shall not be used against Muslim powers. This principle was enunciated by the Khilafat Committee long before the League.” Ambedkar viewed the question of division from the perspective of finance. He found that the Hindu majority provinces raised taxes that totalled nearly Rs 52 crore, whereas the Muslim ones earned a little over Rs 7 crore only.

The Hindus have a difficult choice to make ~ to have a safe Army or a safe border. In the midst of this difficulty, which is the wisest course for the Hindus to pursue? Is it in their interest to insist that Muslim India should remain part of India so that they may have a safe border, or is it in their interest to welcome its separation from India so that they may have a safe Army? In Savarkar’s own words, “several infantile politicians commit the serious mistake in supposing that India is already welded into a harmonious nation, or that it could be welded thus for the mere wish to do so.

These our wellmeaning but unthinking friends take their dreams for realities. It is safer to diagnose and treat deep-seated disease than to ignore it. Let us bravely face unpleasant facts as they are. India cannot be assumed today to be a unitarian and homogenous nation, but on the contrary these are two nations in the main, the Hindus and the Muslims in India.” He insisted that there were two nations, one Hindu and one Muslim. Jinnah wanted India to be divided into two, Pakistan and Hindustan, and the Muslim nation to occupy Pakistan and the Hindu nation to occupy Hindustan.

Savarkar on the other hand insisted that although there are two nations, India should not be divided into two parts; that the two nations should dwell in one country and would live under the mantle of one single Constitution; that the Constitution could be such that the Hindu nation would be enabled to occupy a predominant position that was due to it and the Muslim nation made to live in the position of subordinate cooperation with the Hindu nation. In the struggle for political power between the two nations the rule of the game, which Savarkar prescribed, was to be one manone vote, whether Hindu or Muslim.

In his scheme of things, a Muslim was to have no advantage which a Hindu did not have. Minority was to be no justification for privilege and majority was to be no ground for penalty. Savarkar further held that the State would guarantee the Muslims any defined measure of political power in the form of Muslim religion and Muslim culture. But the State would not guarantee secured seats in the Legislature or in the Administration and, if such guarantee were to be insisted upon by the Muslims, such guaranteed quota was not to exceed their proportion to the general population.

Thus by confiscating its weightages, Savarkar wanted to strip the Muslim nation of all the political privileges it had secured so far. Ambedkar’s comment was that this alternative of Savarkar to Pakistan had a certain frankness, boldness and definiteness which distinguished it from the irregularity, vagueness and indefiniteness that characterized the Congress declarations about minority rights. Savarkar’s scheme had at least the merit of telling the Muslims, thus far and no further. He also felt that the Hindus and Muslims were different people with distinctly separate ethos.

Nevertheless, the country did not need to be divided; it could remain one and it should continue to be one, he believed. The rights and privileges, including votes, should be equal. At the same time, the tune of the Indian polity should be called by the Hindus. He had been candid enough to begin his thesis on this subject, declaring that the punyabhoomi and pitribhoomi of the Christians and Muslims were not in Hindustan, they were abroad. This country therefore was Hindu first and everything else later. How exactly did he propose to reconcile the two opposites?

On the one hand, Savarkar wanted equal rights for all and, at the same time, Hindus to control the country’s destiny. Under no circumstance did he accept the idea of a division of the country. From the beginning of the 20th century, he saw how defensive the Congress had been and how ineffective the Hindu Mahasabha was in curbing Muslim aggressiveness especially after Jinnah had taken fulltime charge of the League on his return from England in 1935. The League had scored points most of the time. Possibly, Savarkar’s love for the country blinded him from the reality that separate nations had to live separately. True until 1941 or even till 1946, no one had witnessed the rioting and the violence that the League had unleashed. Satyagraha was no match for Jinnah’s Direct Action.

As the years have unfolded after Independence, sparks of separation have not disappeared. Even the holy land that was Pakistan split into two within 24 years of its birth. Neither Jinnah nor Savarkar realized that Islam has never believed in a nation and cannot hold it together. It is eminently a binder of the entire ummah. Lately, in even that function, it has become shaky. The Ahmedias were expelled, now the Shias are becoming non-grata, Iran versus Saudi Arabia is hotter than a cold war. Turkey has invaded Syria.

(The writer is an author, thinker and a former Member of Parliament)