‘For it is evident that my religion is a poet’s religion, and neither that of an orthodox man of piety nor that of a theologian. Its touch comes to me through the unseen and trackless channel as does the inspiration of my songs. My religious life has followed the same mysterious line of growth as has my poetical life.

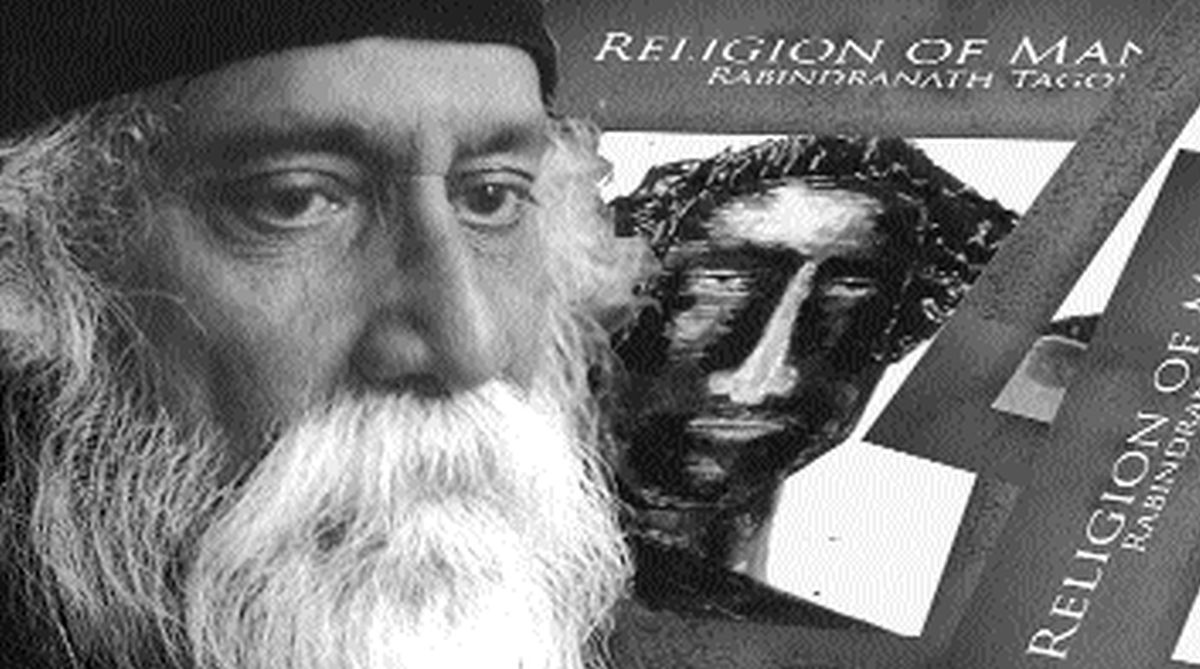

Somehow they are wedded to each other and, though their betrothal had a long period of ceremony, it was kept secret from me’. ~ Rabindranath Tagore in the chapter ‘The Vision’ in The Religion of Man.

‘My religion is my life ~ it is growing with my growth ~it has never been grafted on me from outside.’ ~ Tagore to Robert Bridges, 8 July 1914.

‘Temples and mosques obstruct thy path, / and I fail to hear thy call or to move, /when the teachers and priests angrily crowd round me’. (A Baul song which impressed Tagore and was cited by him in the chapter ‘The Man of my Heart’ in The Religion of Man).

‘The Idea of freedom to which India aspired was based upon realization of spiritual unity…India’s great achievement, which is still stored deep within her heart, is waiting to unite within itself Hindu, Moslem, Buddhist and Christian, not by force, not by the apathy of resignation, but in the harmony of active cooperation.’ ~ Tagore in Berlin, 1921.

‘Patriotism cannot be our final spiritual shelter; my refuge is humanity. I will not buy glass for the price of diamonds, and I will never allow patriotism to triumph over humanity as long as I live.’ ~ Tagore to Aurobindo Mohan Bose on 19 November 1908.

‘Therefore it is said in the Upanishads that advaitam is anantam ~ the One is Infinite; that the advaitam is anandam ~ the One is Love’. To give perfect expression to the One, the Infinite, through the harmony of the many; to the One, the Love, through the sacrifice of self, is the object alike of our individual life and our society.’ ~ Tagore in Creative Unity.

In his work The Religion of Man ~ the Hibbert Lectures for 1930, published in 1931 ~ Tagore compiled his views on religion and philosophy of life. The compilation was by and large based on the Hibbert lectures Tagore delivered at the University of Oxford in 1930.

Given the mad frenzy, hypersensitivity and occasional vindication of ruthless violence in the name of religion in our contemporary world, the prophetic vision of Tagore, (as revealed in his writings and biography) has never been more relevant in modern times.

Tagore’s realizations and observations not only open a spiritual window for seekers of individual salvation, but also serve as a panacea to safeguard all individual faiths from being entrapped within parochial perceptions, inane rituals and radical exploitations.

In fact, Tagore’s lectures and other observations on religion invite his readers to transcend the narrow barriers of conventional faith, thus paving the way for a larger form of internationalism, peaceful co-existence and universal brotherhood.

At the outset, however, in tune with Tagore’s thoughts, it is imperative to capture the right principle behind following any particular faith. In most of his presentations at Oxford, Tagore intended to capture ‘the true spirit of religion’: ‘In them you will see discussed what I consider the true spirit of religion, about my idea of all different religions, what they mean.’ Almost nine decades after his observations were made, even today Tagore’s observations are not only relevant for his countrymen, but for the entire world at large.

Deeply rooted in the Vedantic philosophical thought, Tagore’s religious views were initiated, by and large on conventional lines of traditional faith ~ ‘I was born in a family which, at that time, was earnestly developing a monotheistic religion based upon the philosophy of the Upanishad. Somehow my mind at first remained coldly aloof, absolutely uninfluenced by any religion whatever.’

As he recounts in The Religion of Man: ‘Then came my initiation ceremony of Brahmin-hood when the Gayatri verse of meditation was given to me, whose meaning, according to the explanation I had, runs as follows: Let me contemplate the adorable splendour of Him who created the earth, the air and the starry spheres, and sends the power of comprehension with our minds.’

The ritual of praying and meditating then, as Tagore admitted later in his life, was rather ‘vague’ and unclear. However, in his own words, he recalled the profound impact of chanting his prayer ~ ‘This produced a sense of serene exaltation in me, the daily meditation upon the Infinite being which unites in one stream of creation my mind and the outer world. Though today I find no difficulty in realizing this being as an Infinite personality in whom the subject and object are perfectly reconciled, at that time the idea to me was vague.’

The evolution of Tagore’s religious sensibility went hand in hand with that of his journey as a poet ~ ‘My religious life has followed the same mysterious line of growth as has my poetical life. Somehow they are wedded to each other and, though their betrothal had a long period of ceremony, it was kept secret to me.’

Tagore’s journey as a poet was deeply interlinked with mystical moments of epiphany, which as he proclaimed later, often led to sudden flashes of mystical illumination. He particularly recounts one of his epiphanic moments in his late teens, when the rays of the early dawn sunlight evoked ‘an inner radiance of joy’ in his mind.

Akin to the British Romantic poet William Wordsworth, Tagore’s pantheism or mystical awakening was often refracted through the world of nature. Unlike Wordsworth, however, Tagore articulates his moments of epiphany in considerable detail.

An instance may be cited from his reminiscence recounted in the chapter entitled ‘The Vision’ from The Religion of Man ~ ‘The ordinary work of my morning had come to its close, and before going to take my bath I stood for a moment at my window, overlooking a market-place on the bank of a dry river bed, welcoming the first flood of rain along its channel. Suddenly I became conscious of a stirring of soul within me.

My world of experience in a moment seemed to become lighted, and facts that were detached and dim found a great unity of meaning. The feeling which I had was like that which a man, groping through a fog without knowing his destination, might feel when he suddenly discovers that he stands before his own house.’

It is this deep sense of divine communion and sacred inspiration that coalesced with his vocation as poet and a lyricist. While discussing on ‘The Poet’s Religion’ in Creative Unity (1922) he further clarified, that ‘the ultimate truth in man is not in his intellect or his possessions; it is in his illumination of mind, in his extension of sympathy across all barriers of caste and colour, in his recognition of the world, not merely as a storehouse of power, but as a habitation of man’s spirit, with its eternal music of beauty and its inner light of the divine presence.’

(To be concluded)

The writer is the Dean of Arts, St Xavier‘s College, Kolkata