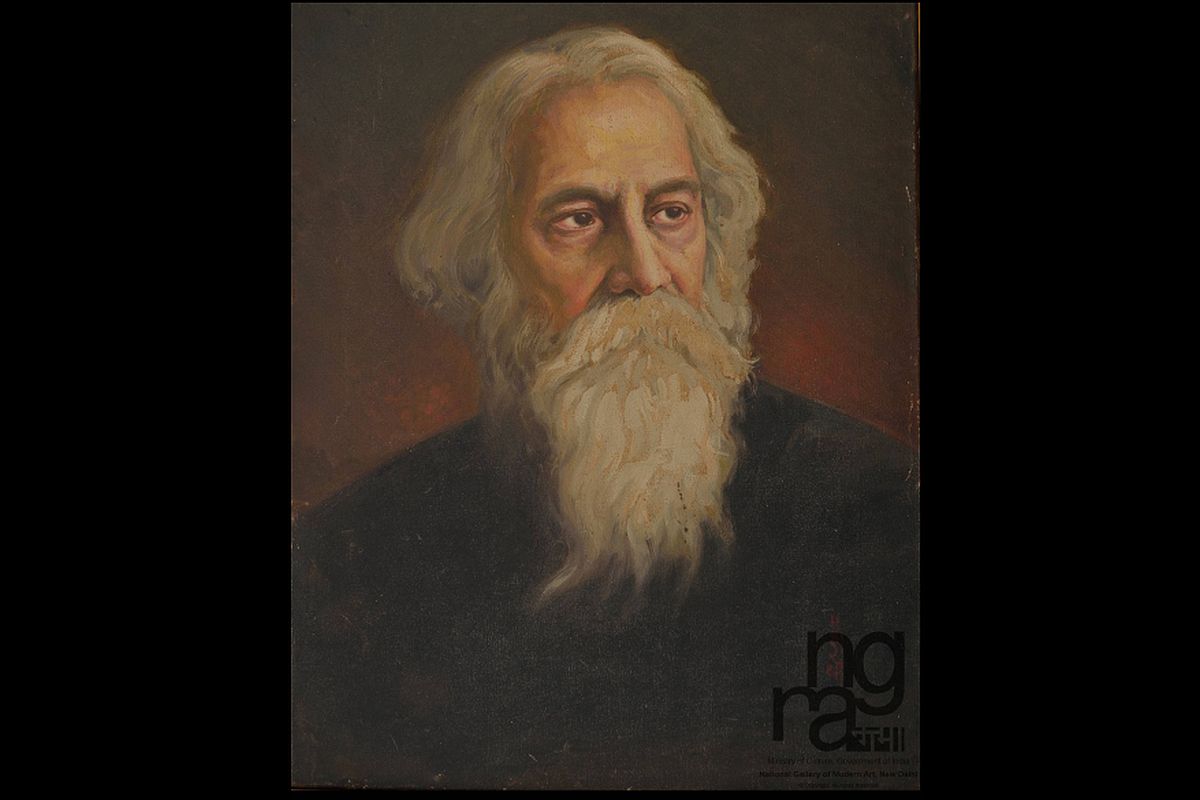

Tagore birth anniversary celebrated across the state

The 164th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore was observed in the state with usual enthusiasm.

Beyond fictional and creative explorations, personal tragic loss to intermittent epidemic outbreaks sometimes paved the way for deeper spiritual contemplation and a larger understanding of life for Tagore

ARGHA KUMAR BANERJEE | New Delhi | December 27, 2020 10:00 am

(Photo: PIB)

In Chaturanga or the Quartet, through the characterization of selfless Jagmohan, Tagore underscores the importance of reaching out beyond boundaries of caste and religion during a pandemic. Through Jagmohan, Tagore also provides his readers with a fictional glimpse of a pandemic-ridden city in grip of utter chaos and panic: “When the plague first came to Calcutta people were more fearful of the uniformed government employees who carted victims off to quarantine than of the disease itself.”

Unlike his brother, the orthodox Harimohan, Jagmohan refused to abandon the tanners of the locality, declining his brother’s offer to seek refuge in the relative safety and isolation of Kalna on the bank of the Ganga. As the disease spread its tentacles, Jagmohan initiated visits to the hospitals of the city engaging himself in the welfare of the victims of the pandemic. Upon his return from the infirmary, reflecting on the ostracism inflicted on victims, he expressed his sheer outrage: “Should the sick be treated like criminals?” Extending his aid, Jagmohan converted his house into a hospital. In his altruistic fervor, Tagore’s fictional protagonist ultimately succumbs after contracting the virulent disease. Commenting on the novel, Tagore’s biographer Krishna Kripalani observes: “Soon after, Calcutta is scourged by plague and as there were not enough hospitals in the city, the humanitarian uncle (Jagmohan) turns his own house into a hospital for the poor, himself nursing the victims. He catches the dreadful disease and dies. ‘He deserved it,’ comments his orthodox brother.”

Advertisement

Jagmohan’s differences with his brother Harimohan primarily lay in the former’s deep concern for the local tanners, many of them belonging to the minority community, whom he refused to abandon. Jagmohan is not an isolated instance of exalted selfsacrifice in a pandemic situation.

Advertisement

In Tagore’s poem ‘Puratan Bhritya’ or the ‘Old Domestic Help’, readers witness a similar character in the domestic help, Keshta. Keshta, who leads a marginalized existence in the zamindar’s house, is also a target of constant abuse being constantly reviled by the zamindar’s wife. Recurrently threatened to leave the household, Keshta exemplifies unswerving loyalty and devotion to his master. So much so, that he even manages to accompany the zamindar on his pilgrimage to Vrindaban ahead of the much-favoured domestic help Nibaran. Keshta proves his mettle and fidelity by conscientiously nursing and saving his master’s life from smallpox in Vrindaban. While fellow pilgrims and others abandoned the zamindar out of sheer panic, Keshta perseveres day and night to save his master from the brink of death. But in the process of displaying such selfless commitment, Keshta contracts the infectious disease and succumbs.

Beyond such fictional and creative explorations, personal tragic loss to intermittent epidemic outbreaks sometimes paved the way for deeper spiritual contemplation and a larger understanding of life for Tagore. The poet suffered personal bereavement from the cholera epidemic when he lost his youngest son Shamindranath in 1907.

As Kripalani observes in Rabindranath ~ A Biography: “In November 1907, came the crowning tragedy of his family life. His youngest son, Samindranath, a handsome and gifted boy who might have become somewhat like his father, suddenly died of cholera…on the same day on which his mother had passed away five years earlier.” Such a personal bereavement however paved the way for a deeper spiritual realization for the poet.

Later in life, while writing a condolence letter from Santiniketan to Maharajkumari Vidyavati Devi (27 December 1935) he recalled the trauma of the demise of his youngest son: “I do not know how adequately to impart my experience to you. I shall simply speak to you of an incident full of the most poignant sorrow of my life. My youngest son, beautiful in appearance and lovable in character, was about sixteen when he was invited to spend his vacation with a friend of his in Monghyr. I hastened to his side when I suddenly received a telegram in Calcutta, informing me of a serious attack of illness causing grave anxiety to his host who was a doctor. The boy lingered for three days after my arrival, trying repeatedly to assure me that he was free from all physical sufferings.”

Tagore’s profound grief perhaps set the way for a larger spiritual transcendence, paving the way for an ingenious flight of the mind in the realm of infinity: “When his last moment was about to come I was sitting alone in the dark in an adjoining room, praying intently for his passing away to his next stage of existence in perfect peace and wellbeing. At a particular point of time my mind seemed to float in a sky where there was neither darkness nor light, but a profound depth of calm, a boundless sea of consciousness without a ripple or murmur.” Such an imaginative flight culminated in an epiphanic vision of spiritual transcendence: “I saw the vision of my son lying in the heart of the infinite and I was about to cry to my friend, who was nursing the boy in the next room, that the child was safe, that he had found his liberation. I felt like a father who had sent his son across the sea, relieved to learn of his safe arrival and success in finding his place.”

The poet’s heartrending personal losses recur in his creative world. However, in the context of discussion of pandemic we find instances of successive deaths in his fiction. In his novel Gora, Harimohini recounts her personal tragedy of losing her son and husband to cholera within just four days: “How could I enjoy such an excess of good fortune without paying a price? My son and husband died of cholera, four days apart. Ishwar the Almighty kept me alive just to demonstrate that human beings can tolerate even the sort of pain that is unimaginable.”

Tagore himself also got actively involved in social service during outbreaks of epidemics in the city. As Kripalani observes: “When, soon after, the plague broke out in Calcutta he assisted Sister Nivedita in organizing relief and medical aid for the victims of this dread pandemic. The poet was turning into a healer of his people’s wounds and a high-priest of their national aspirations, not only raising his voice but lending an active hand in service at the front.’ Yet, Tagore himself was full of praise for Sister Nivedita’s selfless commitment and missionary zeal during the crisis.

Surprisingly, beyond grief, loss, transcendence and active involvement, Tagore, the great writer that he was, also managed to evoke his comic muse amidst ominous circumstances. In ‘The Patient’s Friend’ in Riddle Plays or Hasya Koutuk, through an amusing conversation between the characters Dukhiram and Baidyanath, Tagore explores the lighter side of a pandemic. The exchange of dialogue reveals the fear generated in the mind of Baidyanath due to the halting of the train at Madhupur, an area which had witnessed an outbreak of cholera:

Dukhiram: This is Madhupur. There has been a severe outbreak of cholera epidemic in this area.

Baidyanath: (visibly agitated) Cholera?! What are you saying? Any idea how long the train will halt at this station?

Dukhiram: Half an hour. Given the present circumstances of the deadly epidemic the train should not halt here even for a few minutes. Baidyanath: (in a helpless state) This is really dreadful.

Dukhiram: Getting scared is not a good idea. Ones who get scared contract the disease swifter than others. Trust me, even Dr Larry has written this in his book.

Baidyanath: Please leave me alone. You are only instilling more fear in me. Please summon the doctor. I am already feeling unwell.

Dukhiram: Difficult to find a doctor here.

Baidyanath: Then call the station master.

Dukhiram: It seems the train is about to leave.

Baidyanath: Then summon the rail guard.

Dukhiram: How would he help you?

Baidyanath: (Heaving a deep sigh) Then summon Lord Hari. I am nearing the end of my life (faints in the process of this uttering). (Song: Imagine the doom is near).

Tagore’s reaction to the intermittent outbreaks of pandemics like plague, malaria, cholera and flu reveals various nuances of his deep altruism and compassion for humankind. Readers would do well to reme-mber that the poet-prophet even donned the physician’s role by administering an ayurvedic potion ~ Panchatikta Panchan ~ to his students in Santiniketan to thwart the hazard of the dreaded flu in 1918.

The concoction made of neem leaves (Azadirachta indica), gulancha (Tinospova cordifolia), teuri (Operculina turpethum), thankuni (Centella asiatica) and mishinda (Vitex negundo) worked wonders in boosting their immunity and the poet’s effusion is evident in his epistolary exchange with renowned scientist and close friend Jagadish Chandra Bose in 1919. The letter reveals that though Tagore’s relatives struggled with pneumonia and flu-like symptoms, his students withstood the health hazard of the time: “But none of the boys (students) has got the influenza. I believe it is so because I have been regularly giving them the Panchatikta Panchan. Many of the boys had suffered from the disease during their stay at home in the holidays. Some of them are from the hotspots of the disease and have survived death. I was afraid that they would inadvertently spread the disease here on their return. But nothing of that sort has happened. Even cases of regular fever are fewer this year. Around two hundred people live here, yet the local hospital has almost no patient. This is rather unusual. I am inclined to believe that this is definitely the miracle of the Panchan.”

Advertisement

The 164th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore was observed in the state with usual enthusiasm.

In an age when our interaction with nature is usually at a transactional or mental level, it is instructive and fascinating to see the kind of communion the great poet Rabindranath Tagore had with nature.

When our train arrived at Stratford station, it was still early in the morning. About 150 kilometers northwest of London, in the Warwickshire county of England, sits the market town of Stratford-upon-Avon on the River Avon.

Advertisement