Tagore birth anniversary celebrated across the state

The 164th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore was observed in the state with usual enthusiasm.

Tagore not only denounced class and caste divisions, but he skeptically scrutinized the construction of the nation on narrow parochial lines. ‘I am not against one nation in particular, but against the general idea of all nations. What is the Nation?’ Tagore asks in his famous essay on Nationalism in India.

ARGHA KR BANERJEE | Kolkata | October 24, 2019 1:53 pm

Photo: SNS

Our real problem in India is not political. It is social. This is a condition not only prevailing in India, but among all nations. Therefore, political freedom does not give us freedom when our mind is not free. ~ Tagore in Nationalism in India.

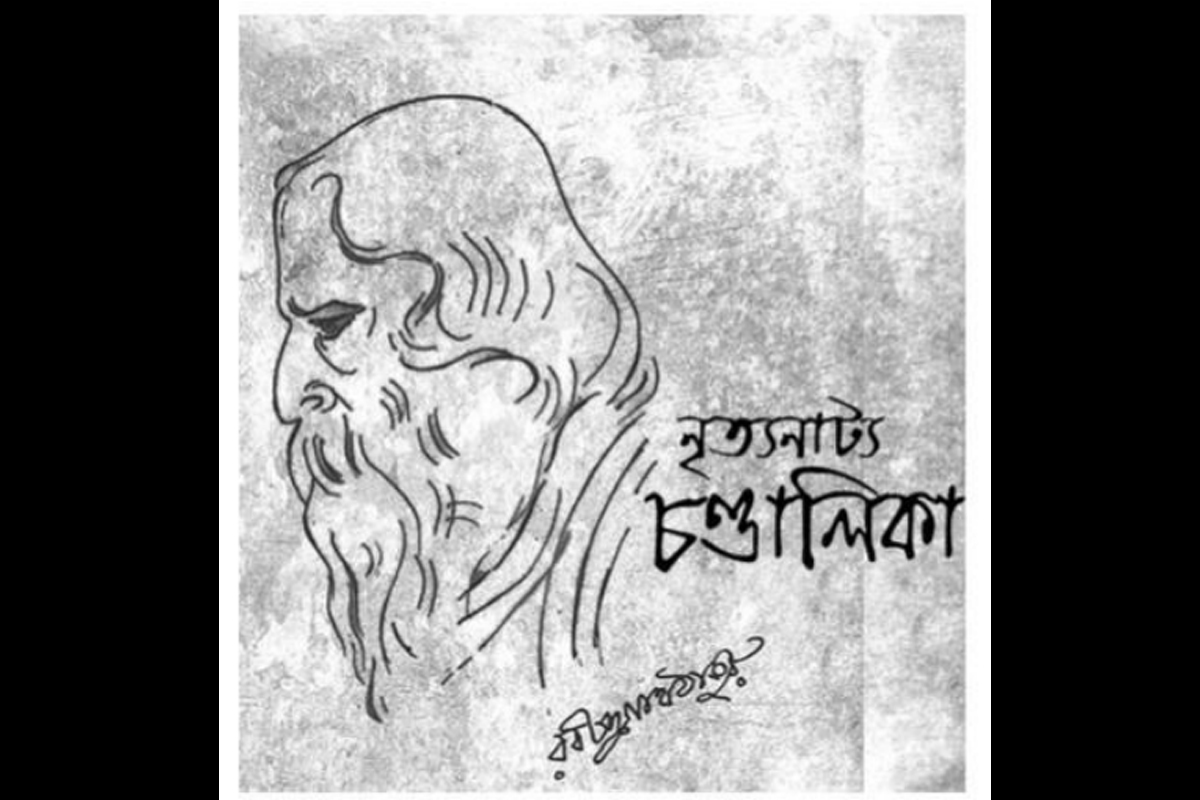

In his dance drama Chandalika, Tagore etches the character of Prakriti, a socially ostracized woman, belonging to the lowest class of society. Inspired by Shardulakarna Avadana, the play clearly reveals Tagore’s attitude towards caste. In fact, through his play, he lampoons the austere Brahmin taboo on interacting with or touching outcastes. In the dance drama, conditioned by the oppressive society, the central female protagonist Chandalika believed in being socially inferior (belonging to the lowest stratum), so much so, that she was convinced of defiling other castes by mere touch or contact. Such a conviction forced her to desist from giving water to the thirsty monk who comes her way. She duly reminds him of her social status as an untouchable, and apologizes for her inability to provide drinking water from the well.

Advertisement

Notwithstanding Prakriti’s inhibition, the Bhikshu insists and drinks water from her, underlining the fundamental spiritual unity of all human beings ~ reminding her not to humiliate herself as: ‘self-humiliation is a sin, worse than selfmurder’. Empowered by this experience and realization, Prakriti managed to disentangle herself from her absurd social entrapments, feeling a deep sense of bliss and enlightenment. However, this true awakening of the self, as the play unravels, also contributed to her obsessive attachment towards the monk. Later in the dance drama, she even vindicates her nascent conviction to her reprimanding mother, who admonishes her, reminding her of her low social status: ‘Once did he cup his hands, to take the water from mine. Such an only little water, yet the water grew to fathomless, boundless sea. In it flowed all the seven seas in one, and my caste was drowned, and my birth washed clean.’

Advertisement

Through the character and experience of Prakriti, Tagore also alludes to the tale of Janaki bathing in the water drawn by Guhak, during the initiation stage of her forest émigré. Sensitized to her own existence as any other human being, irrespective of caste, colour and creed, Prakriti discovers her true self. The rest of the play focuses on the struggle between the sensual and the spiritual, underlining the deep spiritual unity of all human individuals. Prakriti’s self journey in the dance drama is juxtaposed with her conscious negation of her socially forced class and caste, along with her recognition of herself as a confident woman, proud of her own being. By exploring the theme of untouchability in his play, Tagore was also perhaps endorsing Mahatma Gandhi’s pro-Harijan campaign in the 1930s.

At the request of Gandhi, he had contributed the poem ‘The Sacred Touch’ for the Harijan volume 1, no 7 (25th March 1933). The poem explores an anecdote in the life of Saint Ramananda (1400-80), which leads to a deeper realization of humanism, love and inclusivity, as he drew Bhajan the outcast to his heart out of spiritual ecstasy and communion.

Though it is not feasible to accumulate all instances from Tagore’s literary works within the premises of this brief analysis, one obvious example that perhaps would come to the readers’ mind is Tagore’s sympathetic portrayal of the character of ‘Panchu’ in his novel Ghare Baire (The Home and the World). As a representative character of the impoverished struggling peasants of contemporary Bengal, ‘Panchu’ is bereft of a voice in the narrative, being depicted as an oppressed, weak and extremely vulnerable character ~ entirely at the mercy of the warring zamindars ~ an inordinate victim of the then oppressive zamindari system.

Tagore not only denounced class and caste divisions, but he skeptically scrutinized the construction of the nation on narrow parochial lines. ‘I am not against one nation in particular, but against the general idea of all nations. What is the Nation?’ Tagore asks in his famous essay on Nationalism in India. He clarifies it even further, ‘It is the aspect of a whole people as an organized power. This organization incessantly keeps up the insistence of the population on becoming strong and efficient. But this strenuous effort after strength and efficacy drains man’s energy from his higher nature where he is self-sacrificing and creative.’ Tagore’s raison d’être is potent too: ‘For thereby man’s power of sacrifice is diverted from his ultimate object, which is moral, to the maintenance of this organization, which is mechanical.’ What accounts for the immense danger, according to the poet, lies in the false sense or illusion of conviction and fulfillment: ‘yet in this he feels all the satisfaction of moral exaltation and therefore becomes supremely dangerous to humanity.’ In Tagore’s persuasive argument, he asserts the development of the ‘complete moral personality.’

Tagore’s refined sensibility is perhaps rooted in his enlightened family background, which fostered his internationalism at a very young age. Besides coming under the influence of the reformer Raja Rammohan Roy, Rabindranath himself, was deeply conversant with the Upanishads. The reformist Brahmo Samaj that had strong reservations against Hindu orthodox rituals and polytheism perhaps sowed the seeds of an intense spiritual bonding and altruism. As a humanist, Tagore perceived the insular agenda associated with nationalism, especially in the context of India. He flagrantly criticized it for being the root of all problems of the country: ‘Nationalism is a great menace. It is the particular thing which for years has been at the bottom of India’s troubles.’ Though he passed away in 1941, years before India’s political independence, Tagore had misgivings about the nation being driven in the wrong direction, especially when the concept of political freedom is dissociated from ethical and spiritual liberty: ‘Therefore political freedom does not give us freedom when our mind is not free. An automobile does not create freedom of movement, because it is a mere machine. When I myself am free I can use the automobile for the purpose of my freedom.’ He espouses, ‘moral and spiritual freedom’ as the ultimate goal of human life. The impediments that need to be overcome, have been referred to as ‘huge eddies’ by Tagore: ‘In the so-called free countries the majority of the people are not free; they are driven by the minority to a goal which is not even known to them. This becomes possible only because people do not acknowledge moral and spiritual freedom as their object. They create huge eddies with their passions, and they feel dizzily inebriated with the mere velocity of their whirling movement, taking that to be freedom. But the doom which is waiting to overtake them is as certain as death-for man’s truth is moral truth and his emancipation is in the spiritual life.’

This moral and spiritual resilience, according to Tagore, is deeply rooted in India’s identity as a nation and the concept of nationhood. In Nationalism in India*, he points out that unlike other continents, India has ‘tolerated difference of races from the first, and that spirit of toleration has acted all through her history…For India has all along been trying experiments in evolving a social unity within which all the different peoples could be held together, while fully enjoying the freedom of maintaining their own differences.’ Tagore fiercely resisted the division of Bengal in 1905, but ironically the country was partitioned at the time of Independence. According to his ideological prescription, plurality and diversity lie at the root of a dynamic and vibrant India. In the country’s history, perhaps there has never been a greater need than in the present sociopolitical scenario to espouse and re-celebrate the cause of plurality ~ discarding regressive parochial visions of petty nationalism/s for a larger moral and spiritual cause. Instead of thrusting majoritarinism, the polity should devise effective means to permanently ensure peaceful continuity of plurality leaving no opportunity for any religious community or insular social divisions to dominate the land in the future.

The writer is the Dean of Arts, St Xaviers College, Kolkata.

Advertisement

The 164th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore was observed in the state with usual enthusiasm.

In an age when our interaction with nature is usually at a transactional or mental level, it is instructive and fascinating to see the kind of communion the great poet Rabindranath Tagore had with nature.

When our train arrived at Stratford station, it was still early in the morning. About 150 kilometers northwest of London, in the Warwickshire county of England, sits the market town of Stratford-upon-Avon on the River Avon.

Advertisement