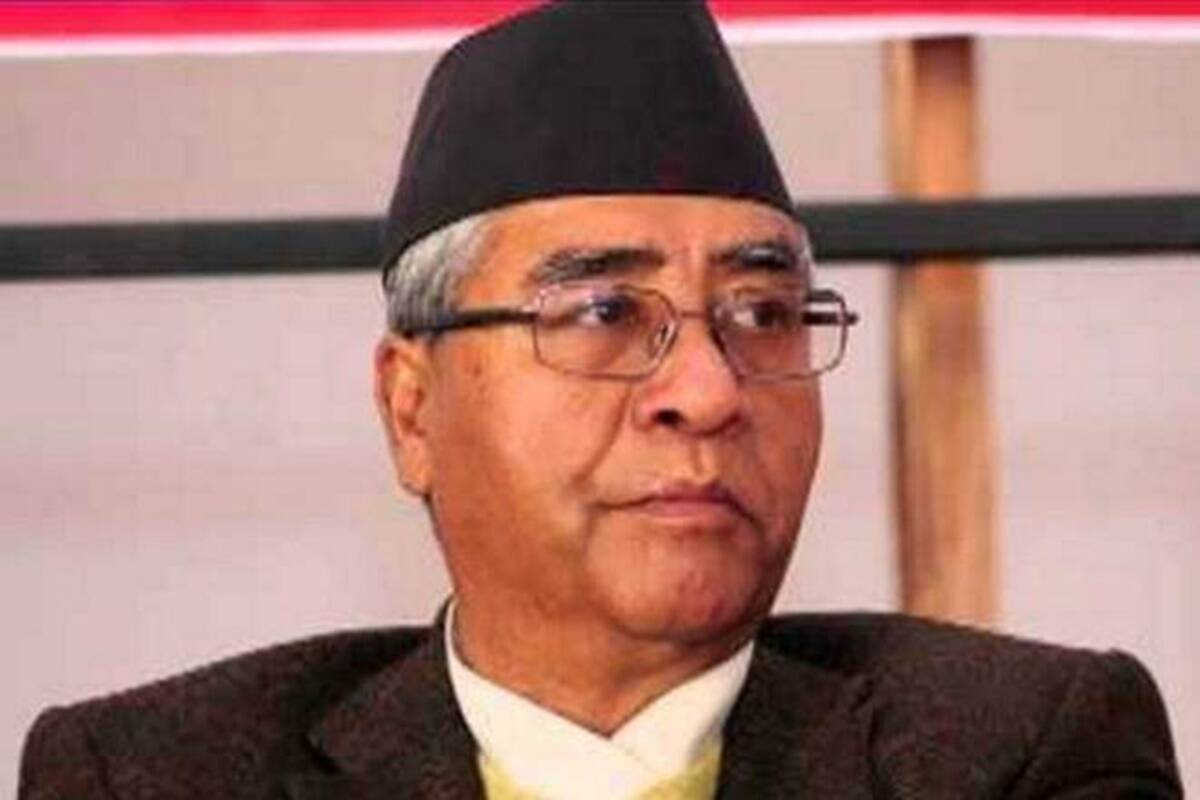

Nepal Premier owes his position to a debatable verdict of the Supreme Court that led to the formation of a desperate coalition of ideologically disparate political parties.

When a two-member bench annulled the formation of the Nepal Communist Party and ordered its two constituents – the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist Leninist) and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) – to begin their unification afresh if they wished so, Premier Deuba’s party became its indirect beneficiary. It emerged as the nucleus of an alternative government.

Advertisement

The timing of the judgment was even more crucial. The verdict of the court had come just before the first session of the reinstated House of Representatives was to begin. Even though in the minority, the “re-recognised” CPN-UML was still the largest party in Parliament. It manoeuvred adroitly and had the lower house dissolved once again through a midnight drama staged at the presidential palace.

The verdict for the second restoration of Parliament was sterner the Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court fixed the date for the next session to begin and issued a mandamus that Deuba be appointed prime minister. All that the presumptive premier needed to do after the order was to cobble together a coalition ministry. That task continues to be a work-in-progress with the Loktantrik Samajbadi Party of Mahantha Thakur waiting in the wings to jump on the gravy train of a government without purpose.

Premier Deuba had repeatedly admitted that he didn’t have the electoral mandate to form the government, and had resisted all requests to move a no-confidence motion against the incumbent. Since the leadership of Parliament has been thrust upon him, he is probably correct in assuming that he is not answerable to the legislature but only to the judiciary that holds the supreme authority of interpreting the constitution.

The Supreme Court, however, is facing a crisis of its own. Due to an impeachment motion, Chief Justice Cholendra Shumsher Rana has been suspended for a month, and the charges levelled against him are likely to draw some more of his colleagues under parliamentary scrutiny. The prolonged confrontation between the Nepal Bar Association and the chief justice stands deferred at the moment, but the image of these institutions of the judicial system will take a while to recover.

With the leadership of the executive practically non-functional and the judiciary malfunctioning, the onus of making the system work lay upon Parliament. Sadly, the legislature has become almost dysfunctional, with the main opposition party obstructing its proceedings for over half a year. The biggest “achievement” of Parliament is that it had succeeded in ratifying the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Compact in the face of considerable resistance from the constituent political parties in government itself.

When all the three branches of government have begun to malfunction from the start, perhaps it’s time to examine whether there is a defect in their design itself. Such an exercise, however, will be considered nothing short of sacrilegious. The dominant community of the country treats the Constitution of Nepal 2015 as a testament of its victory over “fissiparous forces” challenging its hegemony.

Despite the hosannas of its proponents, the merits of democracy aren’t self-evident. Being the oldest, monarchy is one of the most stable forms of government. Intra-clan feuds notwithstanding, the Shah and their Rana cousins kept the country under their grip without any credible challenge for over a century. Dictatorship demands submission from the population and promises a strong government capable of delivering quick results. That was King Mahendra’s pledge when he dissolved Parliament and put almost all cabinet members behind bars.

With criticism stifled and opposition snuffed out altogether, dictators have no excuses to fail. The edifice of “guided democracy” named Panchayat that Mahendra erected lasted almost three decades. Oligarchies are often meritocratic and are popular with the middle class. The revolving door governments of the 1990s in Nepal were not symptoms of democratic deficit alone; they were a result of the meritocratic elite the so-called “people like us” – struggling to retain their primacy.

Democracy promises accountability instead of stability but risks turning majoritarian as it did in 2015 and promulgated a constitution through the shortcut (an accelerated and irregular way of doing things) of fast-track process. It was in the middle of the Gorkha Earthquake aftershocks when Prime Minister Sushil Koirala had told the delegation of the Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities, “Others are saying fast track. But I say mere fast track is not enough; let’s go to double fast track.”

In homogeneous societies, it’s relatively less challenging to create a democratic playground. Heterogeneity gives rise to xenophobia when the dominant majority feels that its hegemony is being challenged in the name of democracy. The majoritarian response then consists of collective narcissism in nationalism, xenophobia to justify prejudice and jingoism to snuff out calls for justice. It results in the rise of demagogic populists mouthing gibberish.

A republic is even more fallible where a leader can interpret the popular mandate to serve as the legitimate authority to rule. Perhaps that’s the trait that made Benjamin Franklin warn a group of citizens after the deliberations of the Constitutional Convention, “A republic if you can keep it.” It’s indeed a short hop from a constitutional republic to an elected autocracy or worse be lured by a demagogic dictator. The road to federalisation is even more arduous and complicated.

To ensure a balance between “self-rule” and “shared rule”, it has to create separate sovereign powers at the federal and provincial levels. Separation of powers and checks and balances at each level are difficult to implement, monitor and rectify regularly. Federalism begins to disintegrate as soon as some politicos or other institutions of the state start to assume the role of being the ultimate protectors of the “national interest”.

The constitution aims to institutionalise a federal democratic republic with a line-up of fossilised leadership of Cold War-era convictions about the red scare and class enemies. They are still prisoners of the monarchist paranoia that national and international conspirators are continuously working to wreck the country’s unity, stability and independence.

No constitution can work if an ethnonational elite is unwilling to give up its privileges. The thar-ghar aristocracy of Gorkha consisted of five Khas-Arya families. The circle has since expanded to include ambitious individuals from the same ethnonational group. Fresh elections are unlikely to break the ethnonational stranglehold. On that bleak note, Happy Holi!

(The Kathmandu Post/ANN)