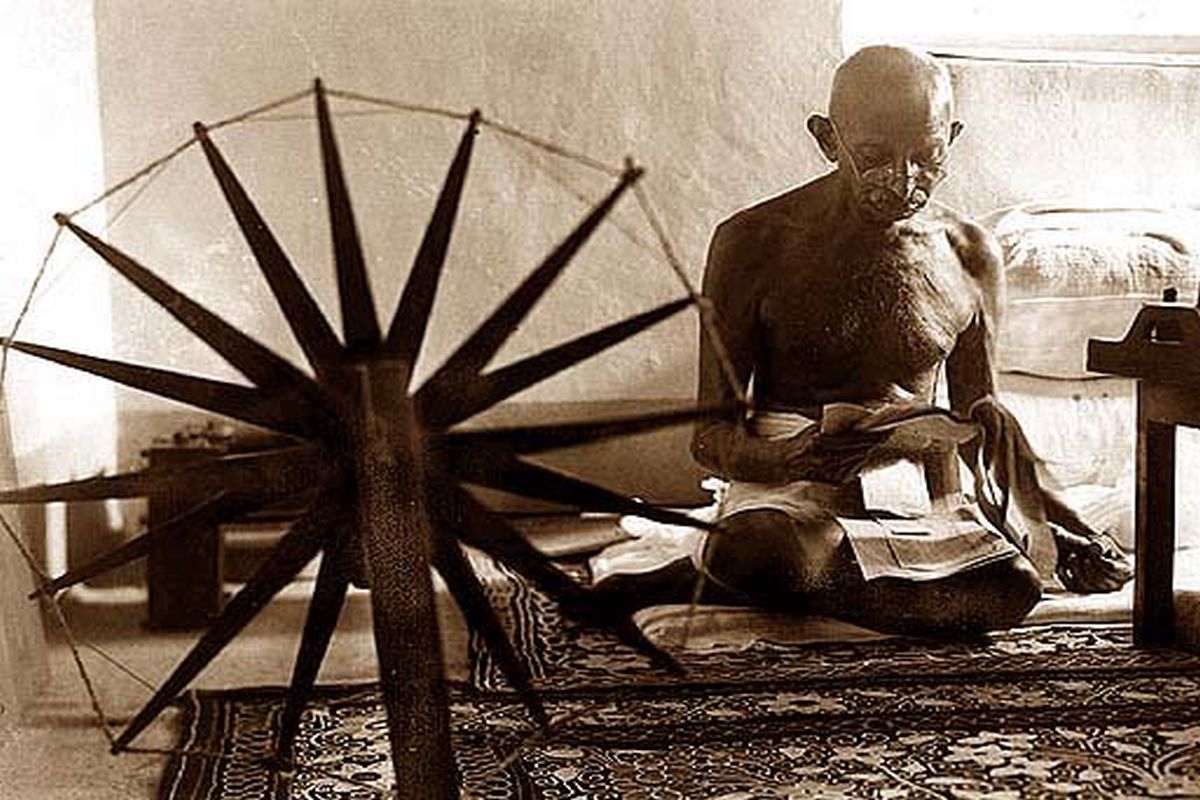

Ramrajya of my dreams ensures equal rights to both prince and pauper. ~ Mahatma Gandhi Mahatma Gandhi’s knowledge of India and its people was profound. Rama of the Ramayana occupies an important space in the hearts of the millions. His awareness of the historical roost of the Indian played a revolutionary because he knew how to make the most of the objective conditions. He could reach the heart of the masses. Gandhi as throughout his life an orthodox Hindu.

In his ideas and methods, in his daily rituals and routine, in his prayer and preaching, in his attempt to rouse the masses through Hindu religious songs, like the Ramdhun, he uttered the name of Rama to reach the heart of the semi-literate and illiterate masses to instill his idea of Ramrajya where ‘the prince and the peasant, the wealthy and the poor, the employer and the employee, are all on the same level.’ Michelet, the French historian, wrote in 1864: “A serene peace reigns there (Ramrajya), in the midst of conflict there is infinite sweetness, a boundless fraternity, which spreads over all things, an ocean of love, of pity, of clemency.’

Advertisement

However, as regards the strategy of the Mahatma, Bernard Shaw once remarked that though Gandhi committed quite a few of tactical errors, his essential strategy continued to be correct. Writing in Young India (September 19, 1929) Gandhi had said: “By Ramrajya I do not mean Hindu Raj. I mean by Ramrajya Divine Raj, the kingdom of God… whether Rama of my imagination ever lived or not on the earth, the ancient deal of Ramrajya is undoubtedly one of true democracy in which the meanest citizen could be sure of swift justice without an elaborate costly procedure. Even the dog is described by the poet to have received justice under Ramrajya.

The ideal Ramrajya, according to Gandhi, may politically be described as ‘the land of dharma and a realm of peace, harmony and happiness for young and old, high and low, all creatures and the earth itself, in recognition of a shared universal consciousness. Indeed, by Ramrajya, Gandhi meant Swaraj or selfrule. In its fullest sense, swarai is much more than freedom from all restraints, it is self-rule and self- restraint and can be equated with moksha or salvation. In fact, the idea of swaraj in India is as old as the Rigveda. It was Gandhi who defined it in its fullness for us particularly as the agenda for postindependence India. This is, in fact, the only social ideal which Gandhi himself had more or less clearly formulated and from which he did not consciously deviate at any stage of his life.

He gave the first systematic exposition of this ideal in his seminal book Hind Swaraj, published in Gujarati in 1909. When Gokhale saw the English translation, on his visit to South Africa in 1921, he feared that Gandhi himself would destroy the book after spending a year in India. Even in 1921, the Mahatma, after carefully reading the book again, said he altered nothing except perhaps the language in some parts. Since the majority of Indians lived in villages, Gandhi saw the revival of villages from their abysmal state as the core of swaraj in free India. He thus coined the term ‘Gram Swaraj’ ~ every village is a republic with legislative, executive and judiciary combined. Although the word swaraj means self-rule, Gandhi envisaged an integral revolution that encompasses all sphere of life.

At the individual level, swaraj is virtually connected with dispassionate self-assessment, ceaseless self-purification and growing swadeshi of self reliance. Politically, swaraj is selfgovernment not good government (for Gandhi, good government is no substitute for self- government) and it means the continuous effort to be independent of government control, whether it is foreign or national. In the other words, it is the sovereignty of the people based on pure moral authority. To achieve Gram Swaraj, Gandhi reminded his colleagues that it would be fruit of the patience, perseverance, ceaseless toil, courage and intelligent appreciation of the environment. Gandhi used to say that ‘Real swaraj will come, not by acquisition of the authority but by the acquisition of capacity by all to resist the authority when it is abused.

In other words, swaraj is to be attained by educating the masses to regulate and control authority.’ Political independence was an essential precondition and exclusively the first step towards realization of swaraj. For political freedom, Gandhi worked with and through the Indian National Congress, but there were serious philosophical and ideological differences between Gandhi and other prominent leaders of the Congress. The development model evolved by Gandhi and enunciated by him in his Hind Swaraj was totally unacceptable and dismissed as ‘completely unreal’ by Nehru. So Gandhi wanted an internal cleansing chiefly through self-motivated voluntary action in the form of constructive work. In his words, ‘ The constructive programme may otherwise and more fittingly be called construction of Poorna Swaraj or complete independence by truthful and non-violent means.

To many thinkers, Gandhi’s concept of ‘Gram Swaraj’ and Ramrajya appears to be utopian ~ a hollow idealism. Indeed, all the philosophies are primarily utopian since they are distant dreams to be achieved. Thomas More, a social thinker of the 18th century, coined the term utopia. In his book entitled Utopia he remarked that all philosophers dream of Utopia till it is not practically applied. We have our own political freedom but we are yet to attain economic, social and moral freedom. These freedoms are harder to attain because they are more constructive and less exciting.

More than seven decades after Independence, poverty and disparity are endemic. Economic growth without social justice is the hallmark of a violent and unsustainable social order. We need to revisit Gandhi’s concept of swaraj and set the course of India’s economic development accordingly. His emphasis is on the maximum striving for the realization of values. The methods prescribed by him cannot be executed on the basis of a shortcut programmatic blueprint. The pragmatic character of his recommendations arises out of his insistence only on the quality of the means and the articulation of the immediate practical step which is consistence with the ultimate values. Gandhi often said after Newman: ‘One step enough for me.’

(The writer is a retired IAS officer)