KMC focus on slum area development for next fiscal

With emphasis on women-centric projects, the city’s slum areas are slated for an infrastructural development in the next fiscal.

All these are combining to make the Sundarbans the most vulnerable region on the planet at the time of global warming.

On 26 May, Cyclone Yaas devastated the east coast in the middle of the second wave of the pandemic.

The high-speed cyclone wind, heavy rainfall and large volume of ocean water coupled with high tidal waves destroyed and submerged large numbers of coastal settlements.

Advertisement

Lakhs of people became homeless and lost their belongings. Thousands of farmers lost their crops in several districts of coastal Odisha and West Bengal. Since the Aila Cyclone in 2009, very severe Cyclones are becoming annual events in the Sundarban area.

Advertisement

This time the path of Yaas was towards the north-west. After landfall south of Balasore in Odisha, it moved towards Jharkhand.

But even 150 to 200 km away from its landfall and path, it caused immense misery to the people of Sundarbans.

Although Yaas has affected vast areas of south Bengal, the most affected areas are around 10 coastal blocks of East Medinipore and all 19 blocks of Sundarbans spread across North and South 24 Parganas.

Last year in May, the Amphan cyclone made its landfall in Sundarbans near Bakkhali and severely affected the lives of people. In May 2019, Cyclone Fani had its landfall near Puri and moved north-east towards Bangladesh but missed the Sundarbans blocks by a whisker.

It is now an established fact that after the 1999 supercyclone of Odisha, the number of tropical cyclones is increasing in the Indian Ocean region. Since long, environmental scientists have warned that climate change is amplifying the cyclonic storms that typically form in the northern Indian Ocean.

Global warming is increasing sea surface temperatures making these cyclones more powerful; rising sea levels are creating higher storm surges reaching larger inland areas and warmer oceans are causing heavy rainfall during storms. Higher temperatures also lead to cyclones forming much faster, as was the case with Amphan and Yaas.

Several documents from expert groups of the IPCC, World Bank, UNEP etc. have highlighted the extreme vulnerability of the Sundarbans. Over the years, systematic disaster preparedness and new warning systems and evacuation procedures by the state have helped to reduce death tolls.

But the loss of properties and livelihoods are increasing disproportionately over time.

The Indian Sundarban with over 9,600 sq. km. delta area with 54 islands, numerous creeks and mangrove forests is an ecologically fragile zone. Half of this land is inhabited by people and the rest is a reserve forest.

This estuary region is composed of estuarine alluvial sediments and much of the area is low lying; it lies below 5 M where the average tidal amplitude ranges from 3.5 to 5.0 M. Over 10 million people are living in 1,100 villages of these extremely vulnerable 19 blocks.

All these are combining to make the Sundarbans the most vulnerable region on the planet at the time of global warming.

During the last two centuries, large numbers of poor and marginal people adopted these inhabitable mangrove-covered saline estuarine lands as their home. With decades of their struggle and toil, they built embankments in the low-lying islands to prevent tidal water from entering.

They created settlement after settlement, dug numerous water bodies for freshwater collection and developed vast agricultural fields. Leveraging their developmental effort recently, big money tourism and industrial fisheries have entered these islands.

Most of the produce, services and labour from this extremely vulnerable landmass in the Indian subcontinent are used by the people of Greater Kolkata.

After the cyclone, many relief initiatives were taken up by the government and civil society, as after previous disasters.

These important initiatives help a large number of victims temporarily, but they cannot support the lives and livelihoods of people for a long time. After Aila, most of the agricultural lands of the Sundarbans were submerged under saline water. The land became unproductive, and it took three to five years to bring these lands back to productivity. A large number of able-bodied people from the Sundarbans migrated to different parts of urban India in search of employment mainly as construction labour.

This time the plight of over 5,000 people of one of the worst-affected islands, Ghoramara, a small island north of Sagar island, is unimaginable. Most of the houses are destroyed. Croplands are flooded with saline water, roads and essential infrastructures are severely damaged and people have no option but to leave the village permanently because of an uncertain future.

But this is not due to one cyclone alone. The hard unknown reality is that in the last three decades over 40 per cent of the land of Ghoramara island has been submerged but the state and society remain indifferent. Like Ghoramara, there are hundreds of villages in the Sundarbans waiting for an activated environmental time bomb, in effect, the next disaster.

If this continues, in the coming years the entire population of the Sundarbans, making up twice the population of Palestine, will become environmental refugees. Only relief and unidirectional engineering solutions like heavy concrete embankments on newly-formed, ever-changing, unstable estuarine soil is not sufficient. Scientists have predicted this for decades but we collectively failed to fathom the gravity and magnitude of the crisis.

Without losing any further time, a time-bound, implementable comprehensive climate resilience action plan for the Sundarbans should be drawn up by a competent, multidisciplinary expert group.

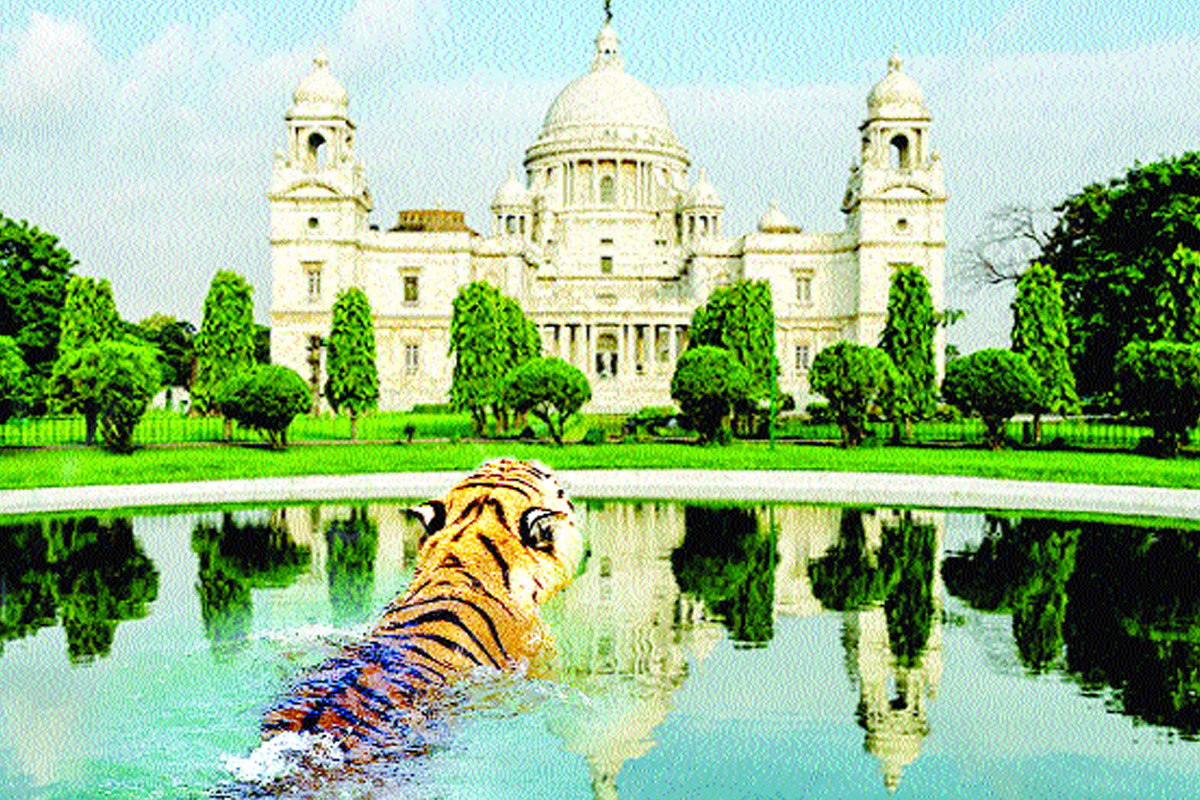

This is an emergency, and it is high time the state and civil society woke up. For, one thing is certain. If the Sundarbans succumb, doomsday for Kolkata won’t be far away.

The writer is Secretary, Integrated River Basin Management Society.

Advertisement